| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Original Article

Volume 2, Number 2, September 2013, pages 68-75

Prophylactic Cervical Cerclage (Modified Shirodkar Operation) for Twin and Triplet Pregnancies After Fertility Treatment

Leonidas Mamasa, b, Eudoxia Mamasa

aNeogenesis IVF centre, 3 Kifissias Ave, 151 23 Marousi, Athens, Greece

bCorresponding author: Leonidas Mamas, Neogenesis IVF Centre, 3 Kifisias Ave, 151 23 Marousi, Athens, Greece

Manuscript accepted for publication May 3, 2013

Short title: Prophylactic Vaginal Cerclage in Multiple Pregnancies

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jcgo143w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Multiple pregnancy rates have increased in the recent years mainly due to an increase in the number of assisted reproduction cycles performed. These pregnancies are associated with maternal and perinatal complications. These complications may arise due to premature delivery. This clinical study was performed in order to assess the effectiveness of prophylactic vaginal cervical cerclage in multiple pregnancies.

Methods: A modified Shirodkar method was applied in twin and triplet pregnancies conceived by fertility treatments, at 13 to 14 weeks of gestation. The suture was fully embedded under the vaginal mucosa in order to avoid the risk of infection.

Results: Our cohort of patients included 31 women with twin and five with triplet pregnancies. The mean gestational age for twins and triplets was 35 + 4 and 33 + 6 and the mean birthweight was 2,267 g and 1,820 g, respectively. Nearly half of the twins and all of the triplets delivered were admitted in the neonatal intensive care unit. Only one neonate had a very low birth weight. No significant differences were noted in the effect of different fertility techniques in the outcome measures studied.

Conclusions: Multiple pregnancies conceived with the aid of fertility treatment benefited from the prophylactic application of a prophylactic cervical vaginal cerclage.

Keywords: Cervical cerclage; Twins; Triplets; Fertility treatment

| Introduction | ▴Top |

With the advent of fertility treatments (for example, In Vitro Fertilisation (IVF), Intrauterine Insemination (IUI) and controlled ovarian stimulation (COS)) thirty years ago, the rate of multiple pregnancies has increased considerably and represents a high proportion of total deliveries [1]. According to the latest data of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), 21.7% of the combined IVF and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles resulted in multiple deliveries in the year 2008. On the other hand, the rate decreased in frozen embryo replacement and IUI cycles [2]. In the United States, twins represent 3 to 4% of all deliveries [3] and of the total multiple births nationwide, 18% were the result of assisted reproductive technologies in 2006 [4].

Multiple gestation pregnancies are associated with a high incidence of maternal and neonatal complications and are thus considered high risk [5-7]. Multiple pregnancies may be associated with a higher rate of perinatal complications due to low birth weight and gestational age (GA) [8]. Spontaneous preterm birth is associated with short cervical length (CL), which is an indicator of preterm delivery [9]. Moreover, the increase of maternal age of patients opting for IVF has resulted in elevated rates of obstetric complications. Studies have suggested that these complications result from maternal characteristics and not the fertility treatment per se [10]. Apart from maternal factors, however, evidence has shown that dizygotic twins after IVF have a higher risk of preterm delivery when compared to non-IVF dizygotic twins [11].

Moreover, a significant increase in the number of infants requiring neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission has been noted. A 7% increase, of NICU admissions following twin deliveries, was reported between 2003 and 2008 [12]. Apart from the associated health risks, management of premature multiple deliveries has increased medical costs. It has been estimated that the cost of preterm deliveries in the US is approximately US $1 billion annually [13].

All the above indicate that decrease of the prematurity rate in multiple deliveries is essential. Several methods have been proposed in order to achieve that. Conflicting opinions exist regarding the effectiveness of bed rest. A small decrease in the number of small for gestational age neonates was noted following antepartum bed rest. However, women showed a high number of depressive-related syndromes [14]. More recent studies concluded that no improvement was observed in the number of very low birthweight infants or neonatal outcomes following hospitalized bed rest [15, 16]. Vaginal progesterone has been shown to be beneficial in high-risk singleton pregnancies. However, in multiple pregnancies, the rate of preterm delivery remained unchanged following the use of vaginal progesterone [17, 18]. Additionally, a recent study showed that the CL decreased during twin pregnancies despite the use 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate [19].

The Arabin cervical pessary has been proposed as a means of preventing preterm delivery. The pessary insertion is a non - invasive, easy procedure that does not require anaesthesia [20]. Its efficacy is controversial and under investigation. A recent study showed that the cervical pessary could prevent preterm delivery in selected singleton - at risk pregnancies following ultrasonographic monitoring of the CL [21].

Transabdominal cervical cerclage (TAC) was first described in 1965 and has been proposed in cases where vaginal cerclage is difficult to perform mainly due to anatomical difficulties [22]. Even though the abdominal approach is beneficial, as the suture can be placed higher on the cervix, the patient must undergo one laparotomy or laparoscopy for placement of the cerclage and a second operation for cesarean delivery [23].

Vaginal cervical cerclage was introduced by Shirodkar and McDonald in the 1950s [24, 25]. A suture is used in order to reinforce the cervix during pregnancy, ultimately increasing the mechanical strength of the cervix and avoiding dilatation and premature delivery.

This study presents the effect of prophylactic vaginal cerclage by a modified Shirodkar operation, with which the suture and the knot of the suture are completely embedded under the vaginal mucosa. The modification was performed in order to reduce the risk of complications caused by infection, for example chorioamnionitis and premature rupture of membranes, in multiple pregnancies conceived with the aid of fertility treatment.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

From 2003 to 2012, women with multiple pregnancies following ICSI, intrauterine tuboperitoneal insemination (IUTPI), a modified IUI procedure [26] and COS were included in the study for prophylactic vaginal cervical cerclage. Women with placenta praevia and active infection were excluded from the study. All women were thoroughly informed prior to the operation, about the procedure, associated benefits and risks and provided written consent.

Prophylactic vaginal cervical cerclage was performed at 13 to 14 weeks of gestation following the nuchal translucency (NT) and nasal bone measurement scan. All women underwent screening for Chlamydia, C-reactive protein (CRP) measurement and vaginal swab culture prior to the cerclage. All operations were performed by the same surgeon at the same private hospital setting.

A modified Shirodkar procedure was performed in all women. The modification in the Shirodkar cerclage used in this study was that the knot of the suture and the suture itself were fully embedded under the vaginal mucosa in order to avoid infection. The procedure was the following. First, the anterior and posterior lip of the cervix, were grasped with Foerster tissue forceps with care not to lacerate the mucosa of the cervix. With the bladder empty the cervix was pulled forward. A 2 cm-long transverse incision in the vaginal mucosa was made on the anterior upper third of the cervix, 2.5 cm above the external os. Blunt dissection with a peanut gauze followed, in order to reveal the cervicovaginal reflection at the level of the internal cervical os. Following that, a round double blunt needle, 65 mm in length and 1.6 mm in diameter, with polyester Mercilene tape 50 cm in length, five mm in width and 0.3 mm in thickness (B. Braun, Germany) was inserted from the right end of the incision at one o’clock under the vaginal mucosa around the cervix and below the sacrouterine ligament at the level of the internal os and exited at the posterior cervix at six o’clock. About 20 cm of the polyester tape was pulled to allow for free movements and the round needle was inserted again at 6 o’clock below the sacrouterine ligament and exited from the left end of the original incision (at 11 o’clock). The suture was tied securely anteriorly. Finally, the knot of the suture was buried in the vaginal mucosa, which was approximated using continuous absorbable 2-0 prolene. Similarly, the suture at the 6 o’clock position (posterior cervix) was buried as well.

All women remained in hospital for monitoring overnight and were then discharged and followed up in the outpatient setting. Monthly CRP and white blood count measurements were performed to monitor for signs of infection.

All pregnancies were then routinely monitored ultrasonographically. Amniocentesis was performed in 11 women over the age of 35 as per protocol after the completion of the second trimester ultrasound, without any complications.

Antenatal corticosteroids, (Betamethasone, Celestone Chronodose (3 + 3) mg/mL, Merck, USA) were administered intramuscularly at 27 weeks and 48 hours prior to planned caesarian section (CS) to promote fetal lung maturation.

All women delivered by elective CS to avoid obstetric and perinatal complications and morbidity that may be associated with multiple deliveries. The date of delivery was decided based on the woman’s characteristics (such as age and body mass index) and following consultation with neonatologists. The suture was removed right after the CS.

| Results | ▴Top |

A total of 36 women, 31 with twin and 5 with triplet pregnancies, underwent prophylactic cervical cerclage. All women shared common demographic characteristics. The mean age was 33.27 (± 3.78) years and the mean BMI was 24.6 (± 3.2).

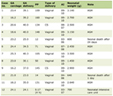

The majority of the pregnancies were the result of ICSI and IUTPI and a smaller percentage from COS (Table 1). All twin pregnancies were dichorionic, diamniotic and all triplet pregnancies were trichorionic, triamniotic.

Click to view | Table 1. Number of Twin and Triplet Pregnancies Conceived by Different Fertility Treatments |

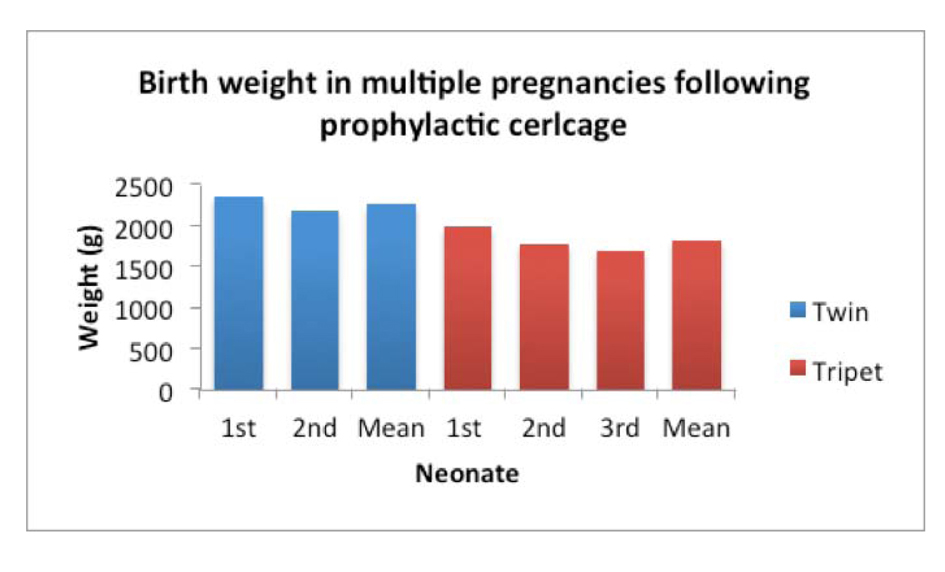

Seventy-seven neonates were delivered over the nine-year study period, 62 from twin pregnancies and 15 from triplet pregnancies. For twin pregnancies, the mean neonatal delivery weight was 2,267 g, with mean weight for 1st and 2nd neonate delivered 2,352 g and 2,182 g respectively. For triplet pregnancies, the mean neonatal delivery rate was 1,820 g with mean weight for 1st, 2nd and 3rd neonate delivered 1,981 g, 1,782 g and 1,696 g respectively (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Birth weight for twins and triplets. The mean BW for 1st, 2nd and 3rd in the case of triplet neonates as well as the overall mean for twins and triplets is indicated. |

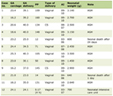

All the pregnancy and neonatal characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The GA for the twin pregnancies was very similar across the three groups ranging from 35 + 1 to 35 + 6 weeks. Within triplet pregnancies the GA was highest for the COS group at 34 + 1 weeks, and slightly reduced for the IVF and IUTPI, at 33 + 4 and 33 + 6 respectively. Among the twins, 51.6% of neonates had to be admitted in the NICU with an average length of stay of 12.2 days. All of the neonates delivered from triplet pregnancies were admitted in the NICU with an average stay of 25.3 days. No significant differences were observed for GA, NICU admissions and length of stay for the neonates across the three different groups. Overall, the male neonates weighed more than the female within twin and triplet deliveries. Differences in the remaining factors varied between the genders but with no statistical significance (t-test, P > 0.05).

Click to view | Table 2. Pregnancy and Neonatal Characteristics of Twin and Triplet Pregnancies Treated With Prophylactic Vaginal Cervical Cerclage |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Multiple gestation is associated with neonatal prematurity, the rate of which increases following ART, especially in cases of extended embryo culture to the blastocyst stage [27] and following COS [28, 29] Additional downsides include elevated health risks for the mother and newborns, increased NICU admissions and cost of treatment [30].

Several ways to increase the GA have been proposed and used, including bed rest, progesterone administration and the Arabin cervical pessary, however none has shown true benefit. Transabdominal cerclage is applicable in cases of shortened or absent cervix or radical trachelectomy [23] and may be used in cases of failed vaginal cerclage [31]. Important drawbacks are, however, associated with transabdominal cerclage. These include, an increased intraoperative risk, due to the position of the abdominal suture, extended hospital stay and increased risk of infection [32].

This study describes the use of a modified Shirodkar method for prophylactic vaginal cervical cerclage, used to increase the GA in multiple pregnancies following fertility treatment. The procedure was performed on 36 women with twin or triplet pregnancies at 13 to 14 weeks of gestation. The timing of the procedure was selected to be after the NT scan and nasal bone assessment. Especially for multiple pregnancies, NT assessment, with the addition of examination of the nasal bone measurement, are considered to detect Down’s syndrome at a 93% rate at 12 weeks gestation [33, 34]. In our study, this stage of pregnancy was chosen to perform the procedure, as it has been shown that cervical shortening may start as early as 11 + 1 weeks in triplet pregnancies [35].

The technique used here is based on the Shirodkar technique described over 60 years ago. Even though the Shirodkar and McDonald techniques are both methods of vaginal cerclage, it has been shown that the Shirodkar technique shows a greater increase in cervical length when measured ultrasonographically [36]. Moreover, the Shirodkar technique is superior in cases where there are altered cervical anatomic conditions [37]. The main difference in the modified Shirodkar technique described in this study is the fact that the cerclage suture is fully embedded under the vaginal mucosa in order to reduce the risk of infection.

Of the 36 women included in the present study, only one showed signs of infection (increased CRP level) at 18 weeks of gestation, four weeks following the procedure. This was treated conservatively with antibiotics. The occurrence of infection (1 in 36) following the cerclage was much lower than that reported in a different study [38]. It has been established that delayed positioning of the cerclage, late in the second trimester, may result in increased risk of chorioamnionitis and premature rupture of the membranes [39]. The procedure in our study was performed in the early second trimester in order to avoid the above-mentioned associated risks.

All women included in the study remained in hospital overnight for monitoring. In 2002, Blair et al compared outpatient with inpatient cervical cerclage. Their results showed that there was a statistically significant higher rate of premature contractions in the outpatient group whereas the inpatient group showed higher rates of delivery of a live neonate [40].

The mean delivery weight for twin A was 2,352 g and twin B 2,182 g. For triplet pregnancies the mean weight was 1,981 g, 1,782 g and 1,696 g for triplet A, B and C, respectively. The average GA for twin pregnancies was 35 + 4 weeks and for triplet pregnancies, 33 + 6. About half the neonates (51.6%) delivered from twin pregnancies were admitted in the NICU, whereas all the neonates from triplet pregnancies had to be admitted. A study of 700 twin pregnancies presented that 60% required NICU admission [41]. In a different study, which investigated the effects of ART in prematurity of twin pregnancies, the mean weight of twin A was 2,011.3 g and for twin B 1,927 g with a mean GA of 33.6 weeks, 46.2% of the first twins and 50% of second twins required admission to the NICU [42]. The same authors in a different study conclude that there is no difference in the risk of prematurity between twin gestations achieved following ART or natural conception [43] further supporting that prophylactic vaginal cervical cerclage may prove to be beneficial in reducing the risk of prematurity even in naturally conceived multiple pregnancies. Another study, where prophylactic cervical cerclage with the McDonald technique was applied to twin pregnancies, resulted in higher average weight compared to those with no prophylactic cerclage [44]. An earlier study, investigating the perinatal outcome between twin pregnancies achieved through ART or spontaneous conception, concluded that the mean GA at delivery was less in the former group and neonatal length of hospital stay was longer [45].

The average duration of stay in NICU for twins was 12.1 days and for triplets 25.3. A study examining the neonatal outcome of IVF/ICSI twins versus twins conceived naturally showed that the average number of days spent in the NICU of the IVF/ICSI twins was 19.8 days [46]. The average duration of stay of our ICSI twins with prophylactic cerclage was 14 days, 5.8 days less than that reported by Pinborg et al, where no prophylactic cervical cerclage was applied. Additionally, a separate study examining the effect of progesterone in the NICU stay of twins showed that after progesterone administration, neonates were hospitalized for 18.4 days compared to 17.3 days of the control group [47], highlighting that progesterone may not be an efficient prophylactic measure in multiple pregnancies when compared to vaginal cervical cerclage.

Multiple pregnancies often show cervical shortening [48]. It has been proposed that bi-weekly ultrasound monitoring of the cervical length in triplet pregnancies is an option and once the cervix is shortened to ≤ 25 mm to proceed to ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage [35] However, it has been shown that ultrasound examination, even of twin pregnancies, shows dynamic, rapid changes of the cervical length in pregnancies delivered preterm, compared to those delivered at term [49]. All of the above indicate that the obstetrician should not only rely on ultrasonic monitoring of the cervix in multiple pregnancies, as the progress of the cervical length in such pregnancies is unpredictable. Moreover, the application of emergency cerclage did not show a good outcome in the majority of twin pregnancies as reported by Gupta et al. Of the 11 applications of emergency cerclage in twin pregnancies, only two showed a good outcome (18%) [50]. This low success rate of emergency cervical cerclage further supports the need for a prophylactic elective cervical cerclage. One of the most important points of this study is the decision to proceed to elective cervical cerclage instead of expectant wait and emergency/rescue cervical cerclage if indicated. The literature so far indicates that emergency cervical cerclage does prolong the pregnancy but shows a high level of chorioamnionitis and preterm premature rupture of the membranes [51, 52].

Corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation were administered in all women at 27 weeks and 48 hours before the CS delivery. Evidence exists that the administration of corticosteroids between 24 and 34 weeks gestation [53] or in repeat doses [54], is beneficial. In our study group only one woman showed preterm premature rupture of the membranes at 32 weeks gestation (1.6%). However, the presence of the cerclage allowed us to delay delivery for 48 hours for the administration of corticosteroids. This may aid in the decrease of the length of stay in NICU as a result of lung maturation. Moreover, all women included in the study following the placement of the cerclage early in the second trimester were able to remain mobile and avoid bed rest.

The beneficial effect of prophylactic cerclage in multiple pregnancies was made apparent more than ten years ago. In 1999, Elimian et al showed that prophylactic cerclage in triplet pregnancies reduced the incidence of extremely low birth weight neonates and the majority of pregnancies delivered after 31 weeks gestation [55].

In our cohort there was only one delivery of a twin with very low birthweight at 1,240 g (< 1500 g, 1.6%). This is a much lower rate of delivery of a very low birthweight baby than that reported by Daniel et al occurring at a rate of 9.7% for the first twin and 15.0% for the second twin within 104 ART-conceived pregnancies [56]. Moreover, Sazonova et al presented a rate of very low birthweight neonates of 5.3%, again higher than the rate reported in this study [57]. No babies were born with extreme low birthweight (< 1,000 g). One of the big advantages of this technique was that all women were able to avoid bed rest and all the psychological and socioeconomic issues associated with it, remaining active during their pregnancy. Despite the fact that the number of cases was low, a benefit of using this modified Shirodkar operation was made apparent with this study. Application of the technique in a larger cohort of cases will confirm these encouraging results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the NICU unit of the IASO Maternity Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Conflict of Interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Beall SA, DeCherney A. History and challenges surrounding ovarian stimulation in the treatment of infertility. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):795-801.

doi pubmed - Ferraretti AP, Goossens V, de Mouzon J, Bhattacharya S, Castilla JA, Korsak V, Kupka M, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2008: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(9):2571-2584.

doi pubmed - Ananth CV, Chauhan SP. Epidemiology of twinning in developed countries. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36(3):156-161.

doi pubmed - Chauhan SP, Scardo JA, Hayes E, Abuhamad AZ, Berghella V. Twins: prevalence, problems, and preterm births. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):305-315.

doi pubmed - Santolaya J, Faro R. Twins—twice more trouble? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(1):296-306.

doi pubmed - Dudenhausen JW, Maier RF. Perinatal problems in multiple births. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(38):663-668.

pubmed - Eskandar M. Outcome of twin ICSI pregnancy compared with spontaneous conceived twin pregnancy: a prospective controlled, observational study. Middle East Fertility Society Journal. 2007;12(2):97-101.

- McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Murphy KE. Preterm birth and low birth weight among in vitro fertilization twins: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;148(2):105-113.

doi pubmed - Fox NS, Rebarber A, Roman AS, Klauser CK, Saltzman DH. Association between second-trimester cervical length and spontaneous preterm birth in twin pregnancies. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(12):1733-1739.

pubmed - Bamberg C, Fotopoulou C, Neissner P, Slowinski T, Dudenhausen JW, Proquitte H, Buhrer C, et al. Maternal characteristics and twin gestation outcomes over 10 years: impact of conception methods. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(1):95-101.

doi pubmed - Kallen B, Finnstrom O, Lindam A, Nilsson E, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. Selected neonatal outcomes in dizygotic twins after IVF versus non-IVF pregnancies. BJOG. 2010;117(6):676-682.

doi pubmed - Bassil KL, Shah PS, Barrington KJ, Harrison A, da Silva OP, Lee SK. The changing epidemiology of preterm twins and triplets admitted to neonatal intensive care units in Canada, 2003 to 2008. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29(4):237-244.

doi pubmed - Bromer JG, Ata B, Seli M, Lockwood CJ, Seli E. Preterm deliveries that result from multiple pregnancies associated with assisted reproductive technologies in the USA: a cost analysis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23(3):168-173.

doi pubmed - Maloni JA, Margevicius SP, Damato EG. Multiple gestation: side effects of antepartum bed rest. Biol Res Nurs. 2006;8(2):115-128.

doi pubmed - Crowther CA, Han S. Hospitalisation and bed rest for multiple pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD000110.

pubmed - Maloni JA. Lack of evidence for prescription of antepartum bed rest. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;6(4):385-393.

doi pubmed - Rode L, Klein K, Nicolaides KH, Krampl-Bettelheim E, Tabor A. Prevention of preterm delivery in twin gestations (PREDICT): a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial on the effect of vaginal micronized progesterone. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(3):272-280.

doi pubmed - Wood S, Ross S, Tang S, Miller L, Sauve R, Brant R. Vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth in multiple pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. J Perinat Med. 2012.

doi pubmed - Lim AC, Schuit E, Papatsonis D, van Eyck J, Porath MM, van Oirschot CM, Hummel P, et al. Effect of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate on cervical length in twin pregnancies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;40(4):426-430.

doi pubmed - Carreras E, Arevalo S, Bello-Munoz JC, Goya M, Rodo C, Sanchez-Duran MA, Peiro JL, et al. Arabin cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in severe twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome treated by laser surgery. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(12):1181-1185.

doi pubmed - Goya M, Pratcorona L, Merced C, Rodo C, Valle L, Romero A, Juan M, et al. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9828):1800-1806.

doi - Benson RC, Durfee RB. Transabdominal Cervico Uterine Cerclage during Pregnancy for the Treatment of Cervical Incompetency. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;25:145-155.

pubmed - Burger NB, Brolmann HA, Einarsson JI, Langebrekke A, Huirne JA. Effectiveness of abdominal cerclage placed via laparotomy or laparoscopy: systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):696-704.

doi pubmed - Shirodkar JN. A new method for operative treatment of habitual abortions in the second trimester of pregnancy. Antiseptic. 1955;52:299-300.

- McDonald IA. Suture of the cervix for inevitable miscarriage. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1957;64(3):346-350.

doi pubmed - Mamas L. Comparison of fallopian tube sperm perfusion and intrauterine tuboperitoneal insemination: a prospective randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(3):735-740.

doi pubmed - Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT, Coutifaris C. Extended embryo culture and an increased risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):69-75.

doi pubmed - Ombelet W, Martens G, De Sutter P, Gerris J, Bosmans E, Ruyssinck G, Defoort P, et al. Perinatal outcome of 12,021 singleton and 3108 twin births after non-IVF-assisted reproduction: a cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(4):1025-1032.

doi pubmed - Morcel K, Lavoue V, Beuchee A, Le Lannou D, Poulain P, Pladys P. Perinatal morbidity and mortality in twin pregnancies with dichorionic placentas following assisted reproductive techniques or ovarian induction alone: a comparative study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153(2):138-142.

doi pubmed - Ericson A, Nygren KG, Olausson PO, Kallen B. Hospital care utilization of infants born after IVF. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(4):929-932.

doi pubmed - Davis G, Berghella V, Talucci M, Wapner RJ. Patients with a prior failed transvaginal cerclage: a comparison of obstetric outcomes with either transabdominal or transvaginal cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(4):836-839.

doi pubmed - Zaveri V, Aghajafari F, Amankwah K, Hannah M. Abdominal versus vaginal cerclage after a failed transvaginal cerclage: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):868-872.

doi pubmed - Krantz DA, Hallahan TW, He K, Sherwin JE, Evans MI. First-trimester screening in triplets. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(4):364 e361-365.

- Nicolaides KH. Screening for fetal aneuploidies at 11 to 13 weeks. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(1):7-15.

doi pubmed - Moragianni VA, Aronis KN, Craparo FJ. Biweekly ultrasound assessment of cervical shortening in triplet pregnancies and the effect of cerclage placement. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(5):617-618.

doi pubmed - Rozenberg P, Senat MV, Gillet A, Ville Y. Comparison of two methods of cervical cerclage by ultrasound cervical measurement. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13(5):314-317.

doi pubmed - Uchide K, Ueno H, Sumitani H, Inoue M. Modifications to the modified Shirodkar operation. Am J Perinatol. 2000;17(8):437-439.

doi pubmed - M DL, Yinon Y, Whittle WL. Preterm premature rupture of membranes in the presence of cerclage: is the risk for intra-uterine infection and adverse neonatal outcome increased? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(4):424-428.

doi pubmed - Charles D, Edwards WR. Infectious complications of cervical cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141(8):1065-1071.

pubmed - Blair O, Fletcher H, Kulkarni S. A randomised controlled trial of outpatient versus inpatient cervical cerclage. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22(5):493-497.

doi pubmed - Hansen M, Colvin L, Petterson B, Kurinczuk JJ, de Klerk N, Bower C. Twins born following assisted reproductive technology: perinatal outcome and admission to hospital. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(9):2321-2331.

doi pubmed - Weghofer A, Klein K, Stammler-Safar M, Barad DH, Worda C, Husslein P, Gleicher N. Severity of prematurity risk in spontaneous and in vitro fertilization twins: does conception mode serve as a risk factor? Fertil Steril. 2009;92(6):2116-2118.

doi pubmed - Weghofer A, Klein K, Stammler-Safar M, Worda C, Barad DH, Husslein P, Gleicher N. Can prematurity risk in twin pregnancies after in vitro fertilization be predicted? A retrospective study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:136.

doi pubmed - Galindo EA, Galache I, Obeso S, Hernandez S, Diaz J, Sepulveda J. Prophylactic cerclage in twin pregnancies from ART: Obstetric outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3):S265.

doi - A B, M K. Outcome of twin pregnancies conceived after assisted reproductive techniques. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2008;1(1):25-28.

doi - Pinborg A, Loft A, Rasmussen S, Schmidt L, Langhoff-Roos J, Greisen G, Andersen AN. Neonatal outcome in a Danish national cohort of 3438 IVF/ICSI and 10,362 non-IVF/ICSI twins born between 1995 and 2000. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(2):435-441.

doi pubmed - Briery CM, Veillon EW, Klauser CK, Martin RW, Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Morrison JC. Progesterone does not prevent preterm births in women with twins. South Med J. 2009;102(9):900-904.

doi pubmed - Skentou C, Souka AP, To MS, Liao AW, Nicolaides KH. Prediction of preterm delivery in twins by cervical assessment at 23 weeks. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;17(1):7-10.

doi pubmed - Bergelin I, Valentin L. Cervical changes in twin pregnancies observed by transvaginal ultrasound during the latter half of pregnancy: a longitudinal, observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(6):556-563.

doi pubmed - Gupta M, Emary K, Impey L. Emergency cervical cerclage: predictors of success. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(7):670-674.

doi pubmed - Nelson L, Dola T, Tran T, Carter M, Luu H, Dola C. Pregnancy outcomes following placement of elective, urgent and emergent cerclage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22(3):269-273.

doi pubmed - Cockwell HA, Smith GN. Cervical incompetence and the role of emergency cerclage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27(2):123-129.

pubmed - Surbek D, Drack G, Irion O, Nelle M, Huang D, Hoesli I. Antenatal corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation in threatened preterm delivery: indications and administration. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286(2):277-281.

doi pubmed - McKinlay CJ, Crowther CA, Middleton P, Harding JE. Repeat antenatal glucocorticoids for women at risk of preterm birth: a Cochrane Systematic Review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):187-194.

doi pubmed - Elimian A, Figueroa R, Nigam S, Verma U, Tejani N, Kirshenbaum N. Perinatal outcome of triplet gestation: does prophylactic cerclage make a difference? J Matern Fetal Med. 1999;8(3):119-122.

doi - Daniel Y, Ochshorn Y, Fait G, Geva E, Bar-Am A, Lessing JB. Analysis of 104 twin pregnancies conceived with assisted reproductive technologies and 193 spontaneously conceived twin pregnancies. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(4):683-689.

doi - Sazonova A, Kallen K, Thurin-Kjellberg A, Wennerholm UB, Bergh C. Neonatal and maternal outcomes comparing women undergoing two in vitro fertilization (IVF) singleton pregnancies and women undergoing one IVF twin pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2012.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.