| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Review Article

Volume 3, Number 2, May 2014, pages 76-79

Bacteroides and Hafnia Infections Associated With Chorioamnionitis and Preterm Birth

Nadeem O. Kaakousha, Julie A. Quinlivanb, George L. Mendzc, d

aSchool of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences, The University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

bSchool of Medicine, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, WA, Australia

cSchool of Medicine, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Darlinghurst, NSW, Australia

dCorresponding author: George L. Mendz, School of Medicine, The University of Notre Dame Australia, 160 Oxford St, Darlinghurst, NSW 2010, Australia

Manuscript accepted for publication March 14, 2014

Short title: Bacteroides and Hafnia Infections During Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo244e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A pregnant woman presented with no signs of infection and gave birth by emergency caesarean section at 27 weeks. Placental histopathology demonstrated moderate histological chorioamnionitis. Microbiology cultures from swabs from the mother’s vagina during labor were reported negative; however, culture-independent analyses returned extensive Bacteroides spp. and Hafnia spp. infections. The case illustrates the importance of testing with non-culture methods for emerging genital infections in pregnancy.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Infection; Preterm birth; Bacteroides; Hafnia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

“Infections of mothers and their babies (both in utero and ex utero) are a major global health challenge.” [1]. Preterm birth (PTB) is the second largest direct cause of child deaths in children younger than 5 years [2], a major cause of perinatal mortality and serious neonatal morbidity, and moderate to severe childhood and life-long disability in developed and underdeveloped countries [3, 4].

Ascending infections from the lower female genital tract into the intra-amniotic cavity are the cause of important morbidities worldwide [5]. These include preterm birth, premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and placental abruption in the mother; sepsis and intrauterine growth retardation in the fetus; septicemia and respiratory and neurological disorders in the newborn [6].

Knowledge of infections during pregnancy remains incomplete, including their prevalence, optimal diagnosis, pathogenic mechanisms and host susceptibilities [7]. A critical step to address this knowledge gap is to obtain a complete understanding of the diverse microbial taxa in the female genital tract in health and disease. The case here reported shows the importance of applying highly accurate, robust, and systematic cultivation-independent analyses to identify and characterize the female genital microbiota, in order better to diagnose infections during pregnancy.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 29-year-old woman (gravida 1 para 0) presented to the birth suite at 27 weeks gestation in her first pregnancy with a history of an antepartum hemorrhage. Apart from a urinary tract infection due to E. coli diagnosed and treated at 10 weeks gestation, the pregnancy had been uncomplicated prior to presentation. On history, the patient reported onset of bleeding an hour before with loss of 50 mL of fresh red blood per vagina. She complained of tenderness across the uterine fundus and reported that her baby had not moved since the bleeding commenced. There was no history of fever or ruptured membranes.

On examination, she appeared anxious, was afebrile and contracting once every 10 min with contractions lasting 25 s. Abdominal palpation demonstrated a tender abdomen, maximally over the uterine fundus. A singleton pregnancy of longitudinal lie, cephalic presentation and occipito-posterior position was noted. The fetal heart rate was 150 beats/min. The fetal cardiotocograph trace demonstrated early decelerations with the mild uterine contractions, but normal beat to beat variability. Vaginal examination demonstrated a closed cervix, 50% effaced, soft and posterior. A diagnosis of abruptio placentae was made.

A swab was collected from the vagina and a urine sample collected, antenatal Celestone therapy, broad spectrum antibiotic therapy and magnesium sulfate for neuroprophylaxis were administered, and the patient was transferred by ambulance to a tertiary facility able to accept a newborn of 27 weeks. At the tertiary facility, following observation for 4 h, the fetal cardiotocograph tracing deteriorated further with a late component to the decelerations and loss of beat to beat variability. An emergency caesarean section delivery was undertaken.

The mother remained afebrile during her hospital course and recovered without adverse event from surgery. The baby was admitted to the level 3 nursery and developed a temperature of 38.8 °C, 3 h after birth. Following blood cultures and swabs, the baby was commenced on broad spectrum antibiotic therapy in addition to requiring rescue surfactant therapy and ventilation. The temperature settled over 30 h. Using standard hospital testing, blood cultures and swabs from the baby and the mother’s vagina during labor were subsequently reported as negative, including specific testing for group B Streptococcus. Histopathology of the placenta demonstrated features consistent with moderate histological chorioamnionitis, with dense infiltration of the chorionic plate and subamniotic tissues by neutrophils. However, no evidence of vasculitis or funisitis of the umbilical cord was noted. At 3-month review mother and baby were doing well. The baby had been discharged home after 12 weeks in hospital and was enrolled in the preterm infant follow-up program.

DNA extraction of the earlier vaginal swab that was preserved cold in a sterile tube was performed using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Chadstone Centre, VIC, Australia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of DNA was measured using a Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies; Wilmington, DE, USA). Tag-encoded amplicon pyrosequencing analyses were performed at the Research and Testing Laboratory (Lubbock, TX, USA) based upon established and validated protocols. The microbial community was assessed by high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene utilizing a Roche 454 FLX instrument with Titanium reagents. The data derived from the high-throughput sequencing process were analyzed employing a pipeline developed at the same laboratory.

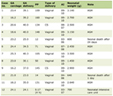

Culture-independent analyses of the microbiota returned that the patient had an extensive Hafnia spp. infection, including a 5.4% content of Hafnia alvei, smaller abundance of Bacteroides spp. and Lactobacillus spp., and negligible presence of other bacteria (Table 1). At the species level of the total bacterial community, 26.1% was Bacteroides fragilis and 6.3% Lactobacillus crispatus.

Click to view | Table 1. Bacterial Genera That Accounted for 96% of All the Taxa Detected in the Vaginal Swab |

The work received ethics approval from the University of Notre Dame Australia Human Research Ethics Committee, registration number 010120S of 18/10/10.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Bacteroides fragilis is involved in gynecological infections and pathology; enterotoxigenic strains have been associated with vaginal disease [8]. The bacterium has been associated with intra-amniotic infections [9], spontaneous mid-gestation abortion and PROM [10]. Nonetheless, a relatively high carriage rate of B. fragilis, including enterotoxigenic strains, without presenting clinical problems was reported amongst pregnant women in Poland [11]. The impact of vaginal colonization by enterotoxigenic B. fragilis and the full spectrum clinical diseases related to it remain to be defined [12].

Phascolarctobacterium spp. are high producers of acetate and propionate short chain fatty acids from fermentation of succinate or lactate, and the genus specializes in the utilization of succinate produced by other bacteria [13]. The detection of bacteria of this genus in the vagina of the patient could be related to the high levels of B. fragilis as bacteria of the genus Bacteroides are major succinate producers [14].

Lactobacilli are considered normal flora of the vagina [15, 16]. Analyses of microbiome data of healthy women from samples in three regions of the vagina, introitus, mid-region and posterior formix, showed that the core vaginal microbiome contained only the genus Lactobacillus; at variance with other body sites, the relative abundance of this genus was very constant between healthy subjects. Principal component analysis suggested the presence of potentially three microbiome types in the vagina: one in which a single Lactobacillus spp. was predominant, and the two most common species were L. crispatus and L. iners [15]. Another microbiome type had as most abundant taxa of the family Bifidobacteriaceae in 5% of the samples. In the third type of vaginal microbiome, taxa were found of the genera Atopobium, Prevotella and Propionobacterium, as well as of the order Clostridiales [17].

Bacteria of the genus Hafnia rarely cause infections in adult humans; most often they colonize the gastrointestinal tract, but also have been isolated from blood, liver abcesses, urogenital and respiratory tracts, and have been the etiological agent of septicemias [18]. The bacterium has been associated with pylonephritis [19, 20]. Owing to an expression of fewer virulence factors than other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family, their role in causing clinically significant infections outside the gastrointestinal tract needs further clarificaton. Its comparatively lower virulence makes Hafnia infection to occur in immnosupressed patients or persons with underlying diseases, and in such instances it has been associated and may be responsible for serious nosocomial or community acquired infections [18]. The rate of isolation of Hafnia alvei is higher in females, and it is most frequently found in polymicrobial cultures [20]. The bacterium has been isolated in Turkish women with cervicovaginitis suggesting that etiologic diagnosis of this disease is required to take appropriate preventive and therapeutic measures [21].

Hafnia pediatric infections are infrequent, and found exceptionally in neonates. There are several reports of Hafnia bacteremias in neonatal intensive care units (NICU) [22-24]. The presence of Hafnia alvei in NICU has caused opportunistic infections in premature newborns undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic invasive procedures. Nosocomial polymicrobial sepsis with positive Hafnia cultures was diagnosed in four premature neonates with intravenous catheters and parenteral feeding, but without previous abdominal pathology or surgery [22]. In another report, polymicrobial cultures that included Hafnia were isolated from the blood of 10 premature infants of gestational ages 24 - 31 weeks. In these neonatal infections, the infants were also subject to invasive procedures [24]. The isolates were resistant to antibiotic treatments with ampicillin and first generation cephalosporins, but susceptible to vancomycin and gentamicin.

The sequencing analyses indicated that 50.1% of the taxa belonged to the genus Hafnia of which 5.4% were identified as H. alvei. The genus Hafnia comprises two species H. alvei and H. paralvei [25]. The results suggested that the rest of the Hafnia taxa belonged to the H. paralvei spp. or to new taxa as yet uncharacterized. Hafnia spp. have different susceptibilities for various antibiotics; a study with 68 clinical isolates demonstrated that more than half of the strains tested were resistant to tetracycline, ampicillin-sulbactam, and first generation cephalosporins [26], and penicillin, oxacillin and amoxicillin/clavulinic acid [19]. Resistance within the genus to beta-lactams, beta-lactam inhibitor combinations, and cephalosporins indicates that some broad spectrum antibiotics will not be effective against this pathogen. Considering also that Hafnia can develop resistance to second and third generation cephalosporins owing to the presence of constitutive and induced beta-lactamases, the empirical treatment to be administered requires careful consideration.

New analytical methods serve to identify with increasing frequency bacterial communities before rarely observed or unknown to colonize the vagina. Many of these species are capable to infect the intra-amniotic space and produce important morbidities; thus, they are categorized as emerging infectious diseases. This case demonstrated the need for cultivation-independent analyses to detect potentially pathogenic species when standard culture-based techniques are negative. Clinical practice should consider broadening the spectrum of bacteria tested to diagnose maternal infections.

Grant Support

This study was supported by a grant from the Cerebral Palsy Institute of the Cerebral Palsy Alliance of Australia. NOK is the recipient of an Early Career Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

| References | ▴Top |

- Hussein J, Ugwumadu A, Witkin SS. Editor's Choice. Brit J Obst Gynaecol. 2011;118(2):i-ii.

doi - Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, Adler A, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2162-2172.

doi - Blencowe H, Lee AC, Cousens S, Bahalim A, Narwal R, Zhong N, Chou D, et al. Preterm birth-associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(Suppl 1):17-34.

doi pubmed - Serenius F, Kallen K, Blennow M, Ewald U, Fellman V, Holmstrom G, Lindberg E, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in extremely preterm infants at 2.5 years after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA. 2013;309(17):1810-1820.

doi pubmed - Mendz GL, Kaakoush NO, Quinlivan JA. Bacterial aetiological agents of intra-amniotic infections and preterm birth in pregnant women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:58.

doi pubmed - Bergstrom S. Infection-related morbidities in the mother, fetus and neonate. J Nutr. 2003;133(5 Suppl 2):1656S-1660S.

pubmed - DiGiulio DB. Diversity of microbes in amniotic fluid. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17(1):2-11.

doi pubmed - Polanco N, Manzi L, Carmona O. [Possible role of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in the etiology of infectious vaginitis]. Invest Clin. 2012;53(1):28-37.

pubmed - Marconi C, de Andrade Ramos BR, Peracoli JC, Donders GG, da Silva MG. Amniotic fluid interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6, but not interleukin-8 correlate with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity in preterm labor. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65(6):549-556.

doi pubmed - Baekelandt J, Crombach M, Donders G, Bosteels J. Spontaneous midgestation abortion associated with Bacteroides fragilis: a case report. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2005;13(4):241-243.

doi pubmed - Leszczynski P, van Belkum A, Pituch H, Verbrugh H, Meisel-Mikolajczyk F. Vaginal carriage of enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis in pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(11):2899-2903.

pubmed - Sears CL. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis: a rogue among symbiotes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):349-369.

doi pubmed - Watanabe Y, Nagai F, Morotomi M. Characterization of Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens sp. nov., an asaccharolytic, succinate-utilizing bacterium isolated from human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78(2):511-518.

doi pubmed - Rotstein OD, Wells CL, Pruett TL, Sorenson JJ, Simmons RL. Succinic acid production by Bacteroides fragilis. A potential bacterial virulence factor. Arch Surg. 1987;122(1):93-98.

doi pubmed - Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4680-4687.

doi pubmed - Structure function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486(7402):207-214.

doi pubmed - Huse SM, Ye Y, Zhou Y, Fodor AA. A core human microbiome as viewed through 16S rRNA sequence clusters. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e34242.

doi pubmed - Gunthard H, Pennekamp A. Clinical significance of extraintestinal Hafnia alvei isolates from 61 patients and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(6):1040-1045.

doi - Loulergue P, Lortholary O, Mainardi JL, Lecuit M. Hafnia alvei endocarditis following pyelonephritis in a permanent pacemaker carrier. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):621.

doi pubmed - Cardile AP, Forbes D, Cirigliano V, Stout B, Das NP, Hsue G. Hafnia alvei pyelonephritis in a renal transplant recipient: case report and review of an under-recognized nosocomial pathogen. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13(4):407-410.

doi pubmed - Ozturk CE, Ozdemir I, Yavuz T, Kaya D, Behcet M. Etiologic agents of cervicovaginitis in Turkish women. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(10):1503-1507.

pubmed - Amil Perez B, Fernandez Colomer B, Coto Cotallo D, Lopez Sastre JB. [Nosocomial Hafnia alvei sepsis in a neonatal intensive care unit]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2004;60(3):271-273.

doi - Casanova-Roman M, Sanchez-Porto A, Casanova-Bellido M. Late-onset neonatal sepsis due to Hafnia alvei. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36(1):70-72.

doi pubmed - Rodriguez-Guardado A, Boga JA, de Diego I, Perez F. [Bacteremia caused by Hafnia alvei in an intensive care neonatal unit]. Med Clin (Barc). 2006;126(9):355-356.

doi - Huys G, Cnockaert M, Abbott SL, Janda JM, Vandamme P. Hafnia paralvei sp. nov., formerly known as Hafnia alvei hybridization group 2. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60(8):1725-1728.

doi pubmed - Abbott SL, Moler S, Green N, Tran RK, Wainwright K, Janda JM. Clinical and laboratory diagnostic characteristics and cytotoxigenic potential of Hafnia alvei and Hafnia paralvei strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(9):3122-3126.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.