| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Case Report

Volume 8, Number 4, December 2019, pages 114-117

Miliary Tuberculosis Presenting as Pyrexia of Unknown Origin in Pregnancy

Tong Carmena, c, Liyana Bte Zailanb, Ravinder Singhb, Ann Wrighta

aKK Women and Children Hospital, 100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 229899, Singapore

bTan Tock Seng Hospital, 11 Jalan Tan Tock Seng, Singapore 308433, Singapore

cCorresponding Author: Tong Carmen, KK Women and Children Hospital, 100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 229899, Singapore

Manuscript submitted August 29, 2019, accepted November 11, 2019

Short title: MTB Presenting as PUO in Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo591

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Miliary tuberculosis (TB) due to the widespread dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains rare, occurring in less than 1-2% of cases, and is usually associated with risk factors including female gender, extremes of age, immunosuppressed states, poor socioeconomic status and alcoholism. Delay in diagnosis or treatment of TB has been associated with poor maternal and fetal outcomes such as anemia, preeclampsia, pneumonia, preterm labor, congenital infection and intra-uterine death. We described a case of miliary TB in pregnancy presenting as prolonged fever with a negative workup showing the challenges in diagnosing miliary TB antenatally, as manifestations can be non-specific and investigation results are inconclusive. This case emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary team, especially of obstetricians with expertise in high-risk pregnancies, infectious diseases, rheumatologists and neonatologists.

Keywords: Tuberculosis; Pregnancy; Infectious disease

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a disease of high burden with an estimated 10.4 million cases and 1.7 million related deaths worldwide reported in 2016 [1, 2]. Diabetes, alcohol, smoking and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positivity contribute substantially to risk burden; and the incidence of TB in men is up to twice that of women [3]. TB prevalence in the USA has been reported at 7.1 per 100,000 pregnancy-related hospitalizations, and in-hospital mortality among TB patients was 37 times greater than that among non TB-infected patients [4]. Miliary TB (MTB) due to the widespread dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains rare, occurring in less than 1-2% of cases, and is usually associated with risk factors including female gender, extremes of age, immunosuppressed states, poor socioeconomic status and alcoholism [5-7]. From 2003 to 2011 TB incidence in pregnancy in the USA increased significantly from 1.92 to 4.06/100,000 births mostly due to non-pulmonary TB [8]. Delay in diagnosis or treatment of TB has been associated with poor maternal and fetal outcomes such as anemia, preeclampsia, pneumonia, preterm labor, congenital infection and intra-uterine death [8-10].

TB is endemic in Singapore. In 2017 the reported incidence rate was 38.7 cases per 100,000 population, although no information was available about TB in pregnancy [11]. A retrospective case review conducted at Singapore General Hospital between 2006 and 2010 found 1,979 cases of notified TB but none in pregnancy [12]. There are few case reports of MTB in pregnancy, and to our knowledge, none so far in Singapore.

We described a case of MTB in pregnancy presenting as prolonged fever showing the challenges in diagnosing MTB antenatally, as manifestations could be non-specific and investigation results were inconclusive.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 26-year-old Malay healthcare worker, gravida 1 para 0, presented at 31 weeks with 3 months of intermittent fever and 1 week of dry cough. Past history included latent TB (LTB) diagnosed 2 years previously for which she had received 6 months of treatment with subsequent TB cultures being negative. This pregnancy had been otherwise uneventful with all routine investigations including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screening being unremarkable.

On admission, she was febrile and tachycardic. Fetal cardiotocography and ultrasound were unremarkable. Initial investigations revealed an elevated white cell count of 15.9 × 109 (predominantly neutrophils), C-reactive protein of 127 mg/L and procalcitonin of 0.14 ng/mL. Chest X-ray suggested patchy changes in the right upper zone. A full septic screen was performed, and she was empirically treated for a bacterial respiratory tract infection with intravenous ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin with no effect. This was switched to intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam to cover for more resistant organisms as her fever persisted.

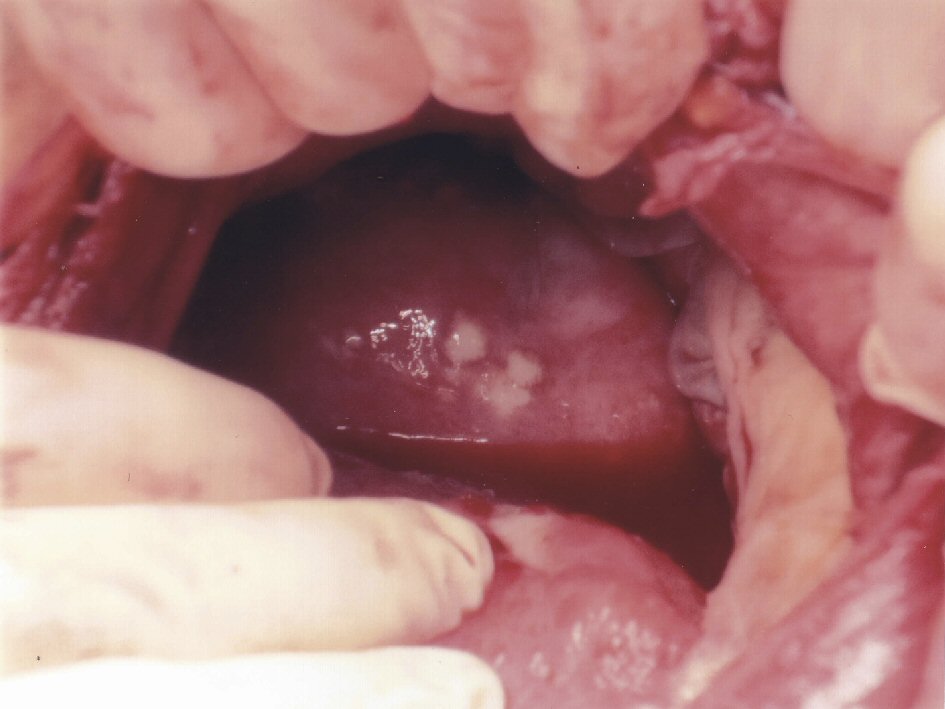

Histology revealed necrotic peritoneal tissue and decidual necrosis on the placenta (Fig. 1). Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was detected on polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Mycobacterial growth was subsequently found in sputum cultures and peritoneal fluid cultures. Further review of the pre-delivery computed tomography (CT) of the thorax by the radiologists confirmed findings compatible with MTB.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Necrotic peritoneal tissue. |

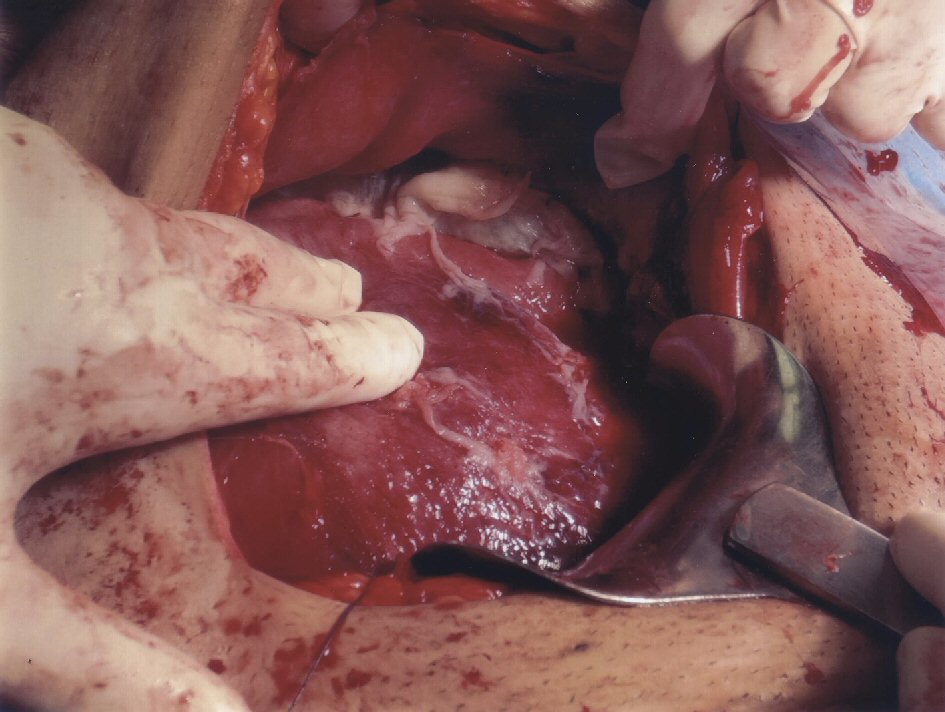

She eventually had a scheduled cesarean section at 35 + 6 weeks for unrelenting fever associated with episodes of fetal tachycardia and weight loss. Intraoperatively, the peritoneum and bowel loops were noted to be thickened and covered with pale inflammatory exudate and widespread adhesions limiting access to the upper abdomen (Fig. 2). A male infant weighing 2,693 g was delivered with Apgar score of 8 at 1 min and 9 at 5 min.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Peritoneum covered with pale inflammatory exudate. |

An atypical pneumonia screen including three sets of acid fast bacilli smears was negative. Other autoimmune tests for pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO) including antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and complement levels were unremarkable. An abdominal and pelvic ultrasound to look for any intra-abdominal pathology showed mild hydronephrosis typically found with a gravid uterus with a small amount of free fluid. A non-contrasted CT scan of the thorax revealed mild scarring with minimal ground glass attenuation in the posterolateral aspects of both lower lobes.

The baby was admitted to the special care unit for prematurity and poor feeding. Subsequent testing revealed no TB, but he was given a 3-month course of prophylactic isoniazid with pyridoxine. The mother was started on standard anti-tuberculous therapy with a good response.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case highlights the importance of TB as a consideration of prolonged fever in an endemic country despite previously treated LTB. It also shows the challenges in diagnosing MTB antenatally as manifestations can be non-specific and investigation results are inconclusive [13]. Pregnancy and up to 180 days postpartum have been reported to increase the risk of reactivation of LTB infection [14]. Despite previous successful treatment, changes in immunity in pregnancy such as downregulation of Th-1 cytokine and natural killer cell cytotoxicity and a reduction in interferon gamma production means that women with LTB are more likely to relapse than males. In our case, diagnosis was eventually made based on the intraoperative findings and subsequent positive cultures with the patient commencing standard treatment comprising isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide with pyridoxine supplementation for 2 months followed by rifampicin and isoniazid for 4 months. These drugs are generally thought to be safe in pregnancy although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises avoidance of pyrazinamide due to a lack of information [15]. The newborn was commenced on isoniazid and pyridoxine for 3 months but monitored for signs of congenital TB which typically presents with respiratory distress in the first month of life with hepatosplenomegaly and failure to thrive. He remained symptom free. Isoniazid can cross the placenta and may cause demyelination, which is why pyridoxine supplementation is given [16, 17]. Rifampicin carries a theoretical risk of teratogenicity and has been implicated in central nervous system and limb reduction abnormalities although the overall risk for congenital malformations has not been found to be increased. It has also been associated with hemorrhagic disorders in the newborn [18]. Ethambutol readily crosses the placenta with a theoretical possibility of ocular toxicity and some reports of teratogenicity in animals, but not in humans [19]. Anti-TB drugs can cross into the breast milk but the amounts are usually too small to produce toxicity with no adverse reports [20, 21].

Differential diagnosis of MTB includes those of infections such as histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, inflammatory disorders such as sarcoidosis and lung malignancy. Rare etiologies such as drug-induced interstitial lung disease should also be considered although less likely in her case [22].

In this case, diagnosis is delayed as investigations such as TB PCR and cultures will take time to return. Concerns regarding administration of contrasted CT thorax in pregnancy will also delay investigations and subsequent diagnosis.

It is important to consider MTB as a diagnosis for PUO in pregnancy especially in endemic populations within Southeast Asia. History and high index of suspicion are key in timely diagnosis and treatment for these patients. Delay in diagnosis or treatment of TB has been associated with poor maternal and fetal outcomes such as anemia, preeclampsia, pneumonia, preterm labor, congenital infection and intra-uterine death. It is crucial for multidisciplinary team involvement in management of complex cases like this for optimal planning of investigations, delivery timing and antibiotic treatment of both mother and fetus.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The author(s) received no funding for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent

The patient’s written consent was obtained for publication of this case.

Author Contributions

Zailan and Tong co-wrote this manuscript with the guidance of Singh and Wright. Tong, Singh and Wright were directly involved in the care of the patient described in the case report.

| References | ▴Top |

- Mert A, Arslan F, Kuyucu T, Koc EN, Ylmaz M, Turan D, Altn S, et al. Miliary tuberculosis: Epidemiologicaland clinical analysis of large-case series from moderate to low tuberculosis endemic Country. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(5):e5875.

doi pubmed - WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report 2017. [Accessed 9 May 2018.] http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/MainText_13Nov2017.pdf?ua=1.

- Collaborators GBDT. The global burden of tuberculosis: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):261-284.

doi - Dennis EM, Hao Y, Tamambang M, Roshan TN, Gatlin KJ, Bghigh H, Ogunyemi OT, et al. Tuberculosis during pregnancy in the United States: Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy complications and in-hospital death. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194836.

doi pubmed - Webster AS, Shandera WX. The extrapulmonary dissemination of tuberculosis: A meta-analysis. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2014;3(1):9-16.

doi pubmed - Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, LoBue PA, Armstrong LR. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(9):1350-1357.

doi pubmed - Abad CLR, Razonable RR. Mycobacterium tuberculosis after solid organ transplantation: A review of more than 2000 cases. Clin Transplant. 2018;32(6):e13259.

doi pubmed - El-Messidi A, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Spence AR, Abenhaim HA. Medical and obstetric outcomes among pregnant women with tuberculosis: a population-based study of 7.8 million births. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6):797.e1-797.e6.

doi pubmed - Bates M, Ahmed Y, Kapata N, Maeurer M, Mwaba P, Zumla A. Perspectives on tuberculosis in pregnancy. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;32:124-127.

doi pubmed - Peng W, Yang J, Liu E. Analysis of 170 cases of congenital TB reported in the literature between 1946 and 2009. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46(12):1215-1224.

doi pubmed - Ministry of Health (MOH). A whole nation approach to prevent the spread of TB. (Accessed 9 May 2018) Available from URL: https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/pressRoom/pressRoomItemRelease/2018/a-whole-of-nation-approach-to-prevent-the-spread-of-tb.html.

- Jappar SB, Low SY. Tuberculosis trends over a five-year period at a tertiary care university-affiliated hospital in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2015;56(9):502-505.

doi pubmed - Sharma SK, Mohan A. Miliary Tuberculosis. Microbiol Spectr. 2017;5(2).

doi - Malhame I, Cormier M, Sugarman J, Schwartzman K. Latent Tuberculosis in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154825.

doi pubmed - Moro RN, Scott NA, Vernon A, Tepper NK, Goldberg SV, Schwartzman K, Leung CC, et al. Exposure to Latent tuberculosis treatment during pregnancy. The PREVENT TB and the iAdhere trials. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(5):570-580.

doi pubmed - Shinohara T, Kagawa K, Okano Y, Sawada T, Kobayashi T, Takikawa M, Iwahara Y, et al. Disseminated tuberculosis after pregnancy progressed to paradoxical response to the treatment: report of two cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:284.

doi pubmed - Ormerod P. Tuberculosis in pregnancy and the puerperium. Thorax. 2001;56(6):494-499.

doi pubmed - Loto OM, Awowole I. Tuberculosis in pregnancy: a review. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:379271.

doi pubmed - Bothamley G. Drug treatment for tuberculosis during pregnancy: safety considerations. Drug Saf. 2001;24(7):553-565.

doi pubmed - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. TB treatment and pregnancy. (Accessed 110/05/2018) Available from URL: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/pregnancy.htm.

- Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos T, Lau J, Ip S. Interventions in primary care to promote breastfeeding: an evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(8):565-582.

doi pubmed - Sharma SK, Mohan A, Sharma A. Challenges in the diagnosis & treatment of miliary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135(5):703-730.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.