| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Original Article

Volume 9, Number 1-2, June 2020, pages 12-16

I-STOP Sling Tape: Is It Associated With Reduced Exposure Rates in Apical Prolapse and Urinary Incontinence Procedures?

David A. Ossina, c, G. Willy Davilab

aDepartment of Urology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

bDorothy Mangurian Comprehensive Women’s Center, 1000 NE 56th Street, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33334, USA

cCorresponding Author: David A. Ossin, Department of Urology, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

Manuscript submitted April 22, 2020, accepted May 22, 2020, published online June 5, 2020

Short title: I-STOP With Low Complication Rates

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo643

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Type 1 polypropylene synthetic mesh has been the preferred mesh material used for reconstructive surgery in the female pelvis in the past. I-STOP is an inelastic monofilament macroporous polypropylene mesh tape with looped edges. Our primary aim was to assess the incidence of mesh complications, including exposure/erosion in women who underwent I-STOP suburethral sling or apical sling suspension procedures.

Methods: This study was a retrospective review of a comprehensive urogynecological database at the Cleveland Clinic Florida of who underwent I-STOP suburethral sling procedures or apical sling suspension between 2009 and 2018. A total of 165 apical slings and 476 suburethral slings were collected at predetermined follow-up visits at 6 weeks, 6 months, and then yearly.

Results: Of the apical slings, 86 (52%) had a follow-up for 6 months or longer, with the maximum patient follow-up of 99 months (mean of 19 months). Zero of the 86 patients that were followed up in the review developed mesh erosion/exposure. A total of 307 (64%) patients who underwent I-STOP suburethral slings had follow-up for 6 months or longer with the maximum patient follow-up of 158 months (mean of 36 months). Two patients developed mesh erosion/exposure with a calculated complication rate at 0.42%. No patients in either group developed clinically evident mesh contraction.

Conclusions: Our study demonstrated lower mesh erosion/exposure and complication rates with the use of the I-STOP tape both in apical sling and suburethral sling procedures compared to complication rates reported with the use of other mesh products.

Keywords: I-STOP tape; Mesh complications; Vaginal mesh; Vaginal sling; Vaginal tapes

| Introduction | ▴Top |

By the age of 80 years, approximately 11% of women in the USA will require surgical intervention for either pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or stress urinary incontinence (SUI) [1]. Up to 29% of these women will undergo repeat surgery for recurrent symptoms [2]. In the hopes of optimizing the results of surgery for POP and/or SUI, use of adjunctive synthetic mesh was popularized over the past 20 years. Although initial experiences with mesh use were overall positive, with increased use adverse outcomes were increasingly reported, limiting its current use. Common complications reported with synthetic mesh include intraoperative bladder perforation, mesh contraction and chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia, infection, fistula formation and mesh erosion [2]. The International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and International Continence Society (ICS) define mesh contraction as the shrinkage in mesh size [3]. Clinical features of mesh contraction include vaginal pain, dyspareunia, and focal tenderness [4].

Mesh exposure or erosion is the most commonly reported complaint by women seeking management of transvaginal mesh complications [5]. Mesh exposure is defined by the IUGA/ICS as a condition of displaying, revealing, exhibiting, or a synthetic implant being accessible [3]. In the study of Kokanali et al, mesh erosion risk factors were traditionally grouped into patient, mesh, and technique/procedure related [6]. In this retrospective study, identified risk factors for mesh complications include increased age, history of diabetes mellitus, smoking, vaginal incision greater than 2 cm, history of previous vaginal surgery and re-incision for postoperative complications [6].

Type 1 polypropylene mesh is currently recognized as the preferred mesh for use in the pelvis. However, type 1 meshes currently on the market differ greatly in construction including weave, mesh weight, and architecture of mesh edges [7]. The I-STOP tape (CL Medical, Winchester, MA) is an inelastic monofilament macroporous polypropylene mesh with looped edges [8]. The specific weave is designed to maintain shape during implantation and incorporation due to the tape’s rigidity [8]. In addition, it is woven in a specific manner to have looped edges theorized to improve tissue fixation and decreased mucosal exposure [8]. These properties translate into reduced complications such as tape contraction and mesh erosion/exposure [8]. Figure 1 is an image of the I-STOP sling tape.

Click for large image | Figure 1. I-STOP sling tape. |

Our hypothesis is that mesh erosion/exposure and contraction rates of I-STOP tapes are lower than those reported with the use of other type 1 synthetic mesh procedures, possibly due to the tape’s unique properties.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was an institutional review board (IRB)-approved retrospective review of a comprehensive urogynecological database at the Cleveland Clinic Florida of women who underwent I-STOP suburethral sling procedures or apical sling suspensions between 2009 and 2018. Our primary aim was to assess the incidence of mesh complications, including exposure/erosion and contraction during the total time of follow-up. Our secondary aim was to assess success rates of apical sling vault suspension based on Pelvic Organ Prolapse-Quantification (POP-Q) stage ≤ 1 (objective) and patient global self-assessment based on the Improvement Satisfaction Scale (ISS) as “cured” or “greatly improved” (subjective). The ISS ranges from cured, greatly improved, somewhat improved, not improved, worsened regarding all pelvic floor symptoms [9]. For I-STOP suburethral sling procedures, our secondary aim was to assess success as the number of episodes of daily stress-associated leakage (objective) and subjective global patient self-assessment (ISS) as “cured” or “greatly improved” (subjective) in women who underwent the procedure for intrinsic sphincteric deficiency. Baseline characteristics assessed included age, menopausal status, history of diabetes mellitus, smoking status, history of genital atrophy, use of vaginal estrogen cream and history of prior vaginal surgery.

Patient selection was based on preoperative pelvic exam identifying defects in apical support requiring surgical repair (with or without additional POP repair procedures). Those patients underwent apical slings with an I-STOP tape placed between the sacrospinous ligaments.

Patients underwent preoperative urodynamic testing to assess for the presence of stress urinary incontinence. Enrolled patients were diagnosed with intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) based on urodynamic findings including a maximum urethral closure pressure (MUCP) < 20 cm H2O and/or leak point pressure (LPP) < 60 cm H2O at 150 mL of capacity. Those subjects underwent a pubovaginal sling with an I-STOP tape due to a higher reported failure rate when using a tension-free midurethral tape [8]. Both suburethral and apical slings were performed under general anesthesia by urogynecologist or urogynecology fellows.

The techniques for suburethral and apical slings have been previously published [8, 10].

I-STOP suburethral pubovaginal sling

A vertical 3 cm incision is made along the anterior vaginal wall, and the fibromuscular layer is dissected off the vaginal epithelium laterally towards the lateral vaginal sulcus and up to the urogenital diaphragm. From a bottom-up fashion, trocars are then guided through the space of Retzius and delivered through ipsilateral suprapubic incisions. Cystoscopy is then performed. The sling tape is passed retropubically and suture fixed at the level of the bladder neck. A cystoscope is held at a 45-degree angle while gentle traction is placed on the sling arms for tensioning. The excess sling is cut at the level of the skin. All incisions are then closed [8].

Apical sling vault suspension

The prolapsed vaginal apex is first marked with three sutures, if needed to identify the cuff. Initially, a traditional posterior vaginal dissection is completed to a distance 1 - 2 cm from the vaginal apex, where the epithelium is left intact for attachment of the apical sling. The pararectal spaces are entered bilaterally to access the sacrospinous ligaments. A Capio suture-capturing device (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) is utilized to place a permanent polypropylene suture through the midportion of the sacrospinous ligaments. A 10-cm portion of the I-STOP sling is attached to the underside of the apex using permanent polypropylene sutures. The permanent suture that were passed through the sacrospinous ligaments are then threaded through the lateral edges of the tape. The closure of the vaginal epithelium is started by closing the proximal posterior incision, and the sacrospinous ligament sutures are tied down while the apex is supported. The rectovaginal fibromuscular layer is attached to the tape with multiple permanent sutures in order to correct any present enterocele. The posterior repair is completed with plication of the fibromuscular layer in a traditional technique. The remaining posterior incision is closed in a running fashion [9].

Data collection

Outcome data were collected at predetermined follow-up visits at 6 weeks, 6 months and yearly for a period of 2 years by urogynecology fellows or urogynecologist. During each visit, subjective outcomes were collected using the ISS, and patients were questioned about any vaginal pain. Physical and pelvic exams were performed to assess degree of pelvic support using Baden-Walker and POP-Q measures, as well as assessment of vaginal mucosal health including the presence of any mesh-related complications such as exposure, erosion, or contraction.

Any additional interventions including mesh revision, additional evaluation or treatment procedures, or other identified complications were recorded.

This study was determined to be exempt from IRB approval as the clinical database used for data collection was IRB-approved by the CCF IRB.

| Results | ▴Top |

A total of 165 apical slings and 476 suburethral slings were reviewed as part of our study. All sequential I-STOP procedures were included.

Of the apical slings, 86 (52%) had follow-up for 6 months or longer, with the maximum patient follow-up of 99 months (mean of 19 months). Zero of the 86 patients that were followed up in the review developed mesh erosion/exposure or contraction. The objective cure rate (anatomical success POP-Q apical prolapse stage ≤ 1) was 100%. The subjective cure rate (patient satisfaction, “cured” or “greatly improved” based on the global ISS) was 57%.

A total of 307 (64%) patients who underwent I-STOP suburethral pubovaginal slings had a follow-up for 6 months or longer with the maximum patient follow-up of 158 months (mean 36 months). Two patients developed mesh erosion (2/476, 0.42%). One patient developed a 3-cm mid-anterior vaginal wall mesh erosion at her 6 weeks follow-up appointment. The other patient developed erosion into the bladder 2 years after undergoing the suburethral sling procedure. Both patients had a history of smoking, and one was a current smoker. Both patients had elevated body mass index (BMI), one was classified as overweight and the other obese. Both patients were managed using minimally invasive approaches. The vaginal exposure was thought to be due to a perioperative vaginal wall hematoma, and was managed via excision of the exposed mesh, with no recurrence. The bladder erosion was managed via suprapubic teloscopy and removal of the mesh eroded into the bladder. Both patients remained continent. The objective cure rate (daily leakage: none or less than daily) was 58%. The subjective cure rate based on the global ISS (patient satisfaction, “cured” or “greatly improved”) was 55%. Urinary retention after suburethral sling placement requiring sling transection occurred in 4% (10/307) of patients. No mesh contractions were identified during the follow-up period.

No other complications were identified. Specifically, no evidence of mesh infection or rejection, other healing abnormalities or vaginal or pelvic pain was reported by subjects or identified on pelvic exam.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Prior published studies on sling procedures for urinary incontinence including 5-year follow-up from the TOMUS trial reported mesh erosion rates ranging from 1.4% to 3.8% [11-14]. A cohort study by Letouzey of 115 patients found a 2.7% erosion rate after bilateral vaginal anterior sacrospinous fixation [15]. A Cochrane review with 583 women who underwent surgical repair of apical prolapse had mesh exposure rates of either 4% (9/291) in vaginal procedures or 3% (8/283) with sacrocolpopexy [16]. Miller et al found that patients who underwent pelvic organ prolapse repair with transvaginal mesh techniques had 18% (16/85) mesh erosion rate over a 5-year follow-up [17]. When other published series on the use of polypropylene mesh kits for POP are summarized, a 10% or greater exposure rate can be expected [18]. There were two abstracts on commercially available polypropylene mesh tape (rather than mesh sheets) kits for apical prolapse, including one review of 10 patients with POP-Q stage 3 apical prolapse followed for a mean of 12 months, and another of 27 patients with greater than POP-Q stage 2 apical prolapse which was followed for a median of 20 months; both noted no vaginal mesh exposure [19, 20]. Our own early experience with I-STOP apical slings and I-STOP pubovaginal slings revealed minimal, if any, complications with the use of the I-STOP tape for these two indications [8, 9].

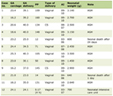

The lower mesh erosion rates in this report could be attributed to various unique factors associated with the I-STOP tape, including lower mesh volumes versus previously used transvaginal mesh techniques [21]. Table 1 listed size of commercial mesh products by area. The reported technique does not utilize mesh for the anterior or posterior repair procedures, and thus the overall mesh volume is more consistent with that used for a suburethral sling than a POP mesh kit. It is thus not surprising that exposure rates are much lower.

Click to view | Table 1. Commercial Mesh Size |

The unique properties of the I-STOP mesh include looped mesh edges and inelastic mesh structure. These predetermined characteristics were designed into the specific weave design of the tape. Specific surgical technique developed for the use of the I-STOP mesh may also helped produce lower rates of mesh erosion. The tapes lay flat without bunching, a characteristic which has been demonstrated on three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound [22].

Our study is limited by patient sample size, a single referral center and one principal surgeon. There were a significant number of patients lost to follow-up, likely due to our institution being a referral tertiary center with patients seen not only from our geographic region, but also internationally.

Our reported subjective success rates were lower than expected as the questionnaire utilized in our validated survey reflects satisfaction with the ISS (a global function satisfaction questionnaire). As such, many patients report, and may be dissatisfied with, persistent voiding dysfunction, overactive bladder symptoms, or dyspareunia which commonly persist after POP or SUI surgery which includes anterior and posterior repairs.

In summary, this study demonstrates very low mesh erosion/exposure, contraction and complication rates with the use of the I-STOP tape for both apical sling and suburethral sling procedures; especially when compared to mesh complication rates reported with other vaginal mesh products. We theorize that the lower mesh load, inelastic weave, looped edges and surgical technique may play a role in the lower than expected mesh complications. The unique construction of the I-STOP tape may be a key factor in lower expected mesh complications, but more studies are needed to determine whether these specific mesh tape features lead to improved outcomes.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

G Willy Davila: acceptance of paid travel expenses or honoraria: Laborie, Astellas, Boston Scientific, and acceptance of payment for research: Pop medical, Coloplast. David Ossin: acceptance of payment for research: CL Medical, Inc.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not required as an IRB-approved clinical database was used.

Author Contributions

DAO contributed to the protocol/project development, data collection or management, data analysis and manuscript writing/editing. GWD contributed to the protocol/project development, data analysis and manuscript writing/editing.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501-506.

doi - Abbott S, Unger CA, Evans JM, Jallad K, Mishra K, Karram MM, Iglesia CB, et al. Evaluation and management of complications from synthetic mesh after pelvic reconstructive surgery: a multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):163 e161-168.

doi pubmed - Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Cosson M, Davila GW, Deprest J, Dwyer PL, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(1):2-12.

doi pubmed - Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 Pt 1):325-330.

doi pubmed - Lee D, Dillon B, Lemack G, Gomelsky A, Zimmern P. Transvaginal mesh kits—how "serious" are the complications and are they reversible? Urology. 2013;81(1):43-48.

doi pubmed - Kokanali MK, Doganay M, Aksakal O, Cavkaytar S, Topcu HO, Ozer I. Risk factors for mesh erosion after vaginal sling procedures for urinary incontinence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:146-150.

doi pubmed - Davila GW, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:7-14.

doi pubmed - Jijon A, Hegde A, Arias B, Aguilar V, Davila GW. An inelastic retropubic suburethral sling in women with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(8):1325-1330.

doi pubmed - Chinthakanan O, Davila GW. Validation of the Improvement Satisfaction Scale (ISS) for organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013:S92-S93.

- Alas AN, Pereira I, Chandrasekaran N, Devakumar H, Espaillat L, Hurtado E, Davila GW. Apical sling: an approach to posthysterectomy vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(9):1433-1436.

doi pubmed - Choo GY, Kim DH, Park HK, Paick SH, Lho YS, Kim HG. Long-term outcomes of tension-free vaginal tape procedure for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Int Neurourol J. 2012;16(1):47-50.

doi pubmed - Gungorduk K, Celebi I, Ark C, Celikkol O, Yildirim G. Which type of mid-urethral sling procedure should be chosen for treatment of stress urinary incontinance with intrinsic sphincter deficiency? Tension-free vaginal tape or transobturator tape. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(8):920-926.

doi pubmed - Oh TH, Shin JH, Na YG. A comparison of the clinical efficacy of the Transobturator Adjustable Tape (TOA) and Transobturator Tape (TOT) for treating female stress urinary incontinence with intrinsic sphincter deficiency: short-term results. Korean J Urol. 2012;53(2):98-103.

doi pubmed - Kenton K, Stoddard AM, Zyczynski H, Albo M, Rickey L, Norton P, Wai C, et al. 5-year longitudinal followup after retropubic and transobturator mid urethral slings. J Urol. 2015;193(1):203-210.

doi pubmed - Letouzey V, Ulrich D, Balenbois E, Cornille A, de Tayrac R, Fatton B. Utero-vaginal suspension using bilateral vaginal anterior sacrospinous fixation with mesh: intermediate results of a cohort study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(12):1803-1807.

doi pubmed - Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD012376.

doi - Miller D, Lucente V, Babin E, Beach P, Jones P, Robinson D. Prospective clinical assessment of the transvaginal mesh technique for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse-5-year results. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2011;17(3):139-143.

doi pubmed - Abed H, Rahn DD, Lowenstein L, Balk EM, Clemons JL, Rogers RG, Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic S. Incidence and management of graft erosion, wound granulation, and dyspareunia following vaginal prolapse repair with graft materials: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(7):789-798.

doi pubmed - Riccetto C, Aguiar T, Azal Jr W, Palma P. Apical sling for site specific pelvic organ prolapse repair. Euro Urol Supplements. 2014;13(1):eV63.

doi - Gonzalez-Lopez R, Gonzalez-Enguita H, Garde-Garcia E, Garcia-Fernandez C. Anterior and apical prolapse treatment with a novel uterine-sparing transvaginal mesh procedure. ICS 2018 Conference Session 36 Abstract 763. Philadelphia. 2018.

- Lenz F, Doll S, Sohn C, Brocker KA. Anatomical position of four different transobturator mesh implants for female anterior prolapse repair. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013;73(10):1035-1041.

doi pubmed - Hegde A, Noguieras M, Aguilar V, Davila G. Comparison of the in vivo deformability of three different sling types on dynamic assessment of sling function. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;25(suppl):S78.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.