| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jcgo.org |

Case Report

Volume 11, Number 1, March 2022, pages 19-22

Leiomyosarcoma in Pregnancy: Incidental Finding During Routine Cesarean Section

Toon Wen Tanga, b, Wai Leng Jessie Phoona

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

bCorresponding Author: Toon Wen Tang, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 100 Bukit Timah Rd, Singapore 229899, Singapore

Manuscript submitted August 23, 2021, accepted September 29, 2021, published online December 8, 2021

Short title: LMS in Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo767

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is an uncommon tumor arising from the female reproductive tract. Incidence of LMS in pregnancy is extremely rare, with only 10 cases reported thus far in medical literature. We present a case of myomectomy performed during elective cesarean section for breech presentation, due to its easy accessibility and well-contracted uterus. Subsequent histology revealed LMS on final specimen. Patient subsequently underwent total abdominal hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. No chemotherapy was given as she opted for close clinical-radiological monitoring instead. This case report highlights the importance of discussion with patients regarding the risk of occult malignancy in a fibroid uterus. Appropriate management of uterine LMS in pregnancy remains unclear. Consideration of removing an enlarging leiomyoma during cesarean section might be ideal in view of its malignant potential, just like in this case; however, location of the tumor and risk of bleeding need to be weighed. Ultimately, management of such cases needs proper discussion between obstetrician and the patient.

Keywords: Leiomyosarcoma; Pregnancy; Cesarean section

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The incidence of uterine leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is uncommon, registering 0.64/100,000 women annually [1]. It accounts for approximately 1.3% of all uterine malignancies. LMS tumors are usually highly malignant neoplasms with an overall poor prognosis. Most commonly, LMS presents after childbearing age, and the reported mean age of patients ranges from 45.0 to 56.9 years old [2, 3]. Occurrence during childbearing age is not common and uterine LMS during pregnancy is even rarer, with only 10 cases reported thus far in medical literature.

Myomectomy is not routinely practiced during cesarean section due to the associated risk of severe hemorrhage. Exceptions include small, pedunculated fibroids; those obstructing the delivery of the fetus or fibroids which are highly suspicious of malignancy based on scans. Therefore, there are cases in which diagnoses of LMS are missed and are only incidentally picked up during cesarean section for other reasons.

We present a case of uterine LMS incidentally diagnosed after elective cesarean section for breech, in which myomectomy was done for an intramural/submucosal fibroid.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 30-year-old gravida 2 parity 2 has been on regular follow-up for her stable fibroid of 5 cm in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital since 2015. She achieved spontaneous pregnancy and regular ultrasonography was done for the follow-up for her fibroid. This fibroid was present in her first pregnancy and grew to 11 cm then, but shrunk back to 5 cm after her first delivery in 2015. In the latter pregnancy in 2018, the uterine mass (what thought to be the fibroid) increased in size and subsequently remained stable throughout the rest of the pregnancy, ranging from 11 to 13 cm.

Diagnosis

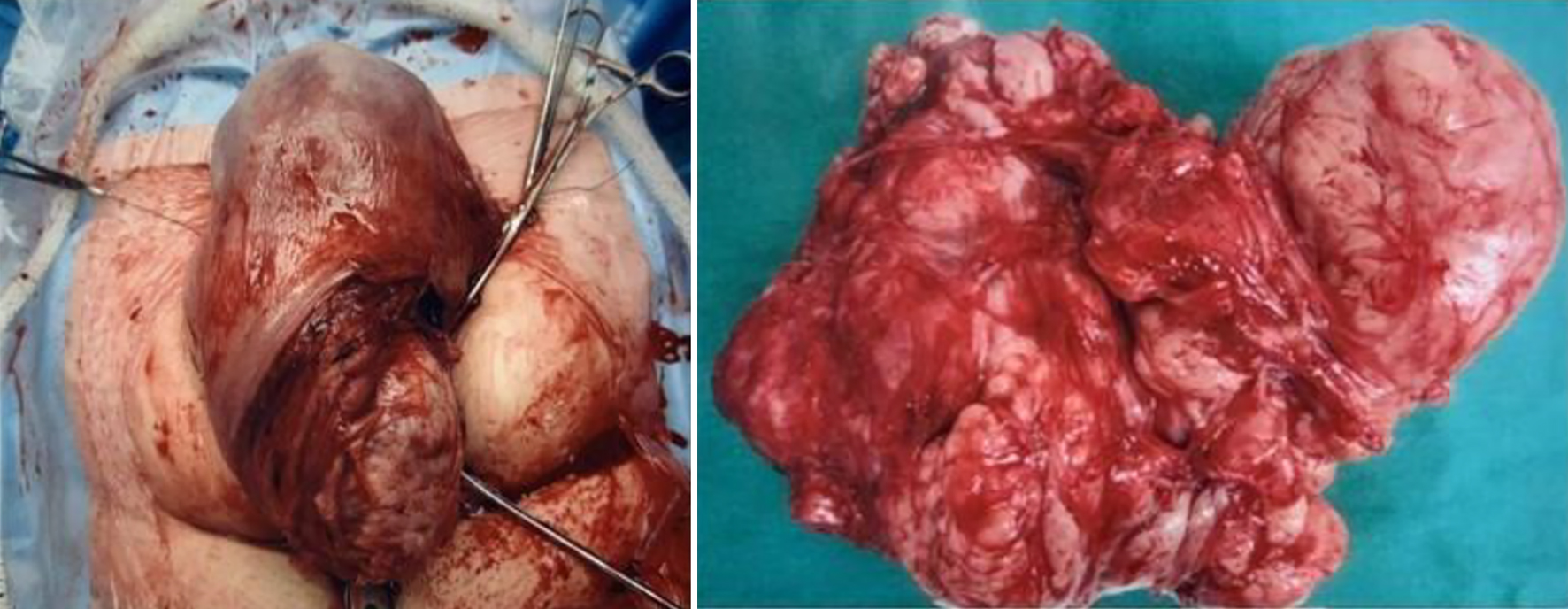

She underwent lower midline cesarean section for breech on December 21, 2018 at 38 + 3 weeks. Intraoperatively, a 19 cm in largest diameter intramural/submucous fibroid was noted in the right lower uterine segment (Fig. 1). Uterine incision was made above the fibroid and baby was delivered via breech extraction. Decision for myomectomy was made as the intramural/submucous fibroid was easily accessible and uterus was well contracted. Fibroid was sent for histology and the report revealed high-grade spindle cell LMS.

Click for large image | Figure 1. The 19-cm intramural/submucous fibroid noted in the right lower uterine segment during cesarean section. |

Treatment

She was recalled back early for computed tomography (CT) of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis on January 22, 2019. Scan showed a stable fibroid corresponding to the one seen on ultrasound previously in 2015, with no radiological evidence of distant metastases.

Completion surgery with total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph nodes dissection and omental biopsy was done on February 14, 2019. Post-operatively, she recovered well and was discharged on post-operative day 3. Histology showed small amount of focal residual LMS within its wall with no evidence of local or distant metastasis.

Follow-up and outcomes

Tumor board discussion was done and staging was confirmed to be stage 1B high-grade LMS. Systemic chemotherapy was recommended in view of high risk of recurrence and medical oncologist was referred. However, patient opted for close clinic radiologic monitoring instead, after weighing the risks and benefits. Till date, her 3 monthly scans showed no evidence of local recurrence and she remains well and healthy.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Uterine LMS is an uncommon smooth muscle tumor and accounts for just 1.3% of all uterine malignancies. Presentation of LMS can include abnormal uterine bleeding, abdominal pain and/or pelvic mass. Incidence of uterine LMS in pregnancy is even rarer and only a total of 10 cases have been reported in medical literature. In addition, all cases of uterine LMS associated with pregnancy from the literature were found incidentally. Similarly to the literature, the diagnosis of LMS for our case was only made histologically, post-cesarean section.

For our case, despite noting the fibroid prior to pregnancy and ensuring regular follow-up scans throughout pregnancy, there were no clinical suspicions to indicate malignancy. Therefore, the tumor was mistakenly diagnosed as leiomyoma. Unlike the case reported by Kyodo et al [4], which was the only case in which myomectomy was performed during cesarean as ultrasonography showed suspicious features; the indication for cesarean in our case was for breech presentation. Additionally, myomectomy was performed in the same setting only because the fibroid was easily accessible (largely submucosal with clear margin capsule) and the uterus was well contracted.

Although a rapidly growing uterus may anecdotally raise concerns regarding uterine sarcoma, pregnancy complicates this as approximately 25% of leiomyomas routinely enlarge during pregnancy due to elevated levels of estrogen and progesterone levels [5]. Estrogen and progesterone have been thought to be the primary promoter of uterine leiomyoma growth. This is based on clinical observation that fibroids only occur after menarche, develop during reproductive years and regress following menopause. This hypothesis is supported by regression of myomas with medical treatment via gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists [6]. Hence, although diagnosis of cancer is unlikely during pregnancy, it is important to be aware of the possibility in order to better counsel patients with a known fibroid to determine the necessity for a myomectomy during the time of delivery.

Nonetheless, myomectomy during cesarean section has and is still a controversial topic due to the attendant risk of severe hemorrhage. Exception includes small, pedunculated fibroids, location at the lower segment in which removal of myoma is mandatory in order for delivery of the fetus. In medical literature, however, there are few studies which directly address this controversy. Case studies by Tinelli et al [7], Ramesh Kumar et al [8], Kanthi et al [9], Li et al [10] and Machado et al [11] have shown that myomectomy during cesarean section can be safe, effective, with minimal intra- and post-operative complications in the hands of experienced surgeons. Review article of nine studies by Song et al [12] concluded that cesarean myomectomy may be a reasonable option in some patients but data driven from the meta-analysis were low quality, and definitive conclusion on this issue cannot be drawn. The recommendation of whether cesarean myomectomy should be done relies entirely on a body of evidence consisting of case series and anecdotes which give conflicting results.

To complicate the issue further, till date, there is no one imaging modality that can accurately and reliably distinguish between benign and malignant leiomyomas. It is thought that pelvic ultrasound followed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging strategy for LMS. Thus, one can consider using MRI postnatally for the follow-up of enlarged fibroids detected before or during pregnancy for early detection of LMS. Sonographic features such as mixed echogenic and poor echogenic parts, central necrosis and colour Doppler findings of irregular vessel distribution in pelvic ultrasound can be suggestive of LMS; however, it may also be present in leiomyomas [13]. Additionally, although scattered hemorrhagic or necrotic mass on MRI should raise a suspicion of LMS, it does not provide a definitive diagnosis. As such, although MRI seems like a promising tool for detection of LMS, it must be taken into consideration that the diagnostic criteria for distinguishing between leiomyoma and LMS are not definitive. Hence, one must weigh the benefits and cost effectiveness of doing MRI postnatally if it does not ensure a definitive diagnosis of LMS.

Primary treatment of LMS is surgery and the standard procedure is total abdominal hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Myomectomy can be considered an alternative if the patient desires future pregnancies, but only if they understand and accept the risk of residual LMS and risk of recurrence. The role of lymphadenectomy for uterine LMS is controversial due to the limited number of studies and conflicting literature. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from uterine LMS is very low and unlikely in absence of extrauterine disease [14]. Therefore, routine lymphadenectomy is not done for patients with localized confined disease and normal lymph nodes on observation and palpation [15, 16]. Another school of thought is that lymphadenectomy may be of clinical benefit for both prognostication and potential palliation by determining the need for adjuvant chemotherapy and pelvic radiotherapy as demonstrated by Giuntoli et al [17]; however, the therapeutic benefit is yet to be proven.

Till date, current literature with regard to role of adjuvant therapy for uterine LMS remains indeterminate. Majority of published studies have reported recurrence rates of 50-60% in early stage uterine LMS. Therefore, adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy, specifically gemcitabine/docetaxel alone or together with doxorubicin, can be beneficial for these groups of patients [18, 19]. Despite a phase III study conducted by the Gynaecologic Oncology Group in 1980s showing a lower recurrence rate in the chemotherapy treated group, the result was not statistically significant and the survival rates were not different between the groups [20]. Given the conflicting evidence, the role of adjuvant chemotherapy remains unclear and should be discussed with the patient, weighing both the benefits and side effects of the treatment.

Learning points

This case report highlights the importance of discussion with patients regarding the risk of occult malignancy in a fibroid uterus and the need for close monitoring of large fibroids antenatally. By doing so, it may be useful in giving a clearer picture of the appropriate management of uterine LMS in pregnancy. Consideration of removing an enlarging leiomyoma during cesarean section might be ideal in view of its malignant potential, just like in this case; however, location of the tumor and risk of bleeding needs to be weighed. Ultimately, management of such cases would require proper discussion between obstetrician and the patient antenatally.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

Dr Wai Leng Jessie Phoon provided expert clinical knowledge to revise clinically. Dr Toon Wen Tang collected data and wrote the paper.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Gallup DG, Cordray DR. Leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: case reports and a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1979;34(4):300-312.

doi pubmed - Park JY, Park SK, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, Nam JH. The impact of tumor morcellation during surgery on the prognosis of patients with apparently early uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(2):255-259.

doi pubmed - Lissoni A, Cormio G, Bonazzi C, Perego P, Lomonico S, Gabriele A, Bratina G. Fertility-sparing surgery in uterine leiomyosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70(3):348-350.

doi pubmed - Kyodo Y, Inatomi K, Abe T. Sarcoma associated with pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161(1):94-96.

doi - Matsuo K, Eno ML, Im DD, Rosenshein NB. Pregnancy and genital sarcoma: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Perinatol. 2009;26(7):507-518.

doi pubmed - Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D. Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(8):1037-1054.

doi pubmed - Tinelli A, Malvasi A, Mynbaev OA, Barbera A, Perrone E, Guido M, Kosmas I, et al. The surgical outcome of intracapsular cesarean myomectomy. A match control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(1):66-71.

doi pubmed - Kumar RR, Patil M, Sa S. The utility of caesarean myomectomy as a safe procedure: a retrospective analysis of 21 cases with review of literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(9):OC05-08.

doi pubmed - Kanthi JM, Sumathy S, Sreedhar S, Rajammal B, Usha MG, Sheejamol VS. Comparative study of cesarean myomectomy with abdominal myomectomy in terms of blood loss in single fibroid. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2016;66(4):287-291.

doi pubmed - Li H, Du J, Jin L, Shi Z, Liu M. Myomectomy during cesarean section. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(2):183-186.

doi pubmed - Machado LS, Gowri V, Al-Riyami N, Al-Kharusi L. Caesarean Myomectomy: Feasibility and safety. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12(2):190-196.

doi pubmed - Song D, Zhang W, Chames MC, Guo J. Myomectomy during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121(3):208-213.

doi pubmed - Buzinskiene D, Mikenas S, Drasutiene G, Mongirdas M. Uterine sarcoma: a clinical case and a literature review. Acta Med Litu. 2018;25(4):206-218.

doi pubmed - Harry VN, Narayansingh GV, Parkin DE. Uterine leiomyosarcomas: a review of the diagnostic and therapeutic pitfalls. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2007;9(2):88-94.

doi - Leitao MM, Sonoda Y, Brennan MF, Barakat RR, Chi DS. Incidence of lymph node and ovarian metastases in leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(1):209-212.

doi - Goff BA, Rice LW, Fleischhacker D, Muntz HG, Falkenberry SS, Nikrui N, Fuller AF, Jr. Uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma: lymph node metastases and sites of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50(1):105-109.

doi pubmed - Giuntoli RL, 2nd, Metzinger DS, DiMarco CS, Cha SS, Sloan JA, Keeney GL, Gostout BS. Retrospective review of 208 patients with leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: prognostic indicators, surgical management, and adjuvant therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89(3):460-469.

doi - Hensley ML, Ishill N, Soslow R, Larkin J, Abu-Rustum N, Sabbatini P, Konner J, et al. Adjuvant gemcitabine plus docetaxel for completely resected stages I-IV high grade uterine leiomyosarcoma: Results of a prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):563-567.

doi pubmed - Hensley ML, Wathen JK, Maki RG, Araujo DM, Sutton G, Priebat DA, George S, et al. Adjuvant therapy for high-grade, uterus-limited leiomyosarcoma: results of a phase 2 trial (SARC 005). Cancer. 2013;119(8):1555-1561.

doi pubmed - Omura GA, Blessing JA, Major F, Lifshitz S, Ehrlich CE, Mangan C, Beecham J, et al. A randomized clinical trial of adjuvant adriamycin in uterine sarcomas: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(9):1240-1245.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.