| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jcgo.org |

Original Article

Volume 11, Number 1, March 2022, pages 9-13

Is the Admission Cardiotocography Test Predictive of an Emergent Cesarean Delivery During Labor in Prolonged Pregnancies?

Audrey Astruca, Caroline Verhaeghea, Guillaume Legendrea, Philippe Descampsa, Romain Corroennea, b

aDepartment of Obstetrics, Angers University Hospital, Angers, France

bCorresponding Author: Romain Corroenne, Department of Obstetrics, Angers University Hospital, 49100 Angers, France

Manuscript submitted January 23, 2022, accepted February 21, 2022, published online March 12, 2022

Short title: Admission Test in Prolonged Pregnancies

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo791

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The aim of the study was to evaluate if an admission cardiotocography (CTG) test presenting with an indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing (FHR) was predictive of an emergent cesarean delivery during labor at or after 41 weeks.

Methods: This was a retrospective cohort study of women who delivered ≥ 41 weeks between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019. Admission test was performed during the first 20 min, upon entry into the department in the event of spontaneous labor, or at the beginning of induction of labor. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to evaluate an “indeterminate” FHR during the admission test in the prediction of emergent cesarean delivery during labor controlling for potential covariables.

Results: “Normal” and “indetermediate” FHRs were detected in 260/335 (77.6%) and 75/335 (22.3%) of the cases, respectively. There were significantly more emergent cesarean deliveries during labor for FHR abnormalities in the “indeterminate” group compared to the “normal” group (22/38 (57.9%) vs. 24/27 (88.9%), P = 0.02). An “indeterminate” FHR increased the risk of emergent cesarean delivery during labor by 3.47 times (95% confidence interval: 1.8 - 6.5, P < 0.01).

Conclusion: An “indeterminate” FHR during the admission test ≥ 41 weeks increased the risk of emergent cesarean delivery during labor.

Keywords: Admission test; Antepartum FHR testing; Obstetrics; Fetal assessment; Prolonged pregnancy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

In France, prolonged pregnancies (≥ 41 weeks) represent 15% of pregnancies [1]. Several authors have shown a correlation between prolonged pregnancies and maternal and neonatal morbidity [2, 3]. Prolonged pregnancy presents an increased risk of stillbirth, oligoamnios, fetal heart rate (FHR) abnormalities and in utero passage of meconium [2, 3]. Also, the risks of neonatal acidosis, an Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 min, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit and neurological complications gradually increase after 38 weeks [3].

The admission cardiotocography (CTG) test is a record of the FHR over a period of 20 min, immediately after admission to the labor ward with the objective to early detect endangered fetus and reduce materno-fetal morbidity [4]. Indeed, admission CTG test is a dynamic screening test for the state of fetal oxygenation by recording fetal heart. Based on the analysis of uterine contractions, baseline FHR, variability, presence of accelerations, periodic or episodic decelerations and the changes in these characteristics over time, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has defined three categories of FHR tracings: “normal” (category 1), “indeterminate” (category 2), and “abnormal” (category 3) [5]. Although an “abnormal” (category 3) FHR (bradycardia or repeated profound decelerations) requires an emergent cesarean delivery, little is known about the neonatal prognosis in case of “indeterminate” FHR during admission CTG test in prolonged pregnancy.

The objective of our study was to evaluate if an admission CTG test presenting “indeterminate” (category 2) FHR according to the ACOG classification was predictive of an emergent cesarean delivery for non-reassuring fetal status during labor in prolonged pregnancy (≥ 41 weeks). The secondary objective was to compare neonatal outcomes between fetuses who presented a “normal” admission CTG test and those with an “indeterminate” admission CTG test.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This retrospective cohort study was performed in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Angers University Hospital between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2019. We included all women who delivered at or beyond 41 weeks. We excluded patients for whom data were retrospectively missing, patients with an “abnormal” (type 3) FHR during admission CTG test according to ACOG [5], patients who underwent a cesarean delivery before labor at or beyond 41 weeks (breech presentation or mother choices), high-risk pregnancies and patients with maternal or fetal diseases. This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee of Angers University Hospital (2019/56), and was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects as well as with the Helsinki Declaration.

From 41 weeks, clinical examination of the women, FHR recording and ultrasound evaluation of the amniotic fluid quantity were performed every 48 h [3]. Induction of labor was performed based on maternal choice, maternal-fetal abnormality or in the absence of spontaneous labor at 41 weeks + 4 days. Induction of labor was performed according to standard obstetrical cares by an artificial rupture of the membranes following with oxytocin perfusion. When cervical ripening was necessary, it was performed either by mechanical methods (intra-cervical balloon) or by intra-vaginal prostaglandins [3].

The admission CTG test was performed during the first 20 min of recording of the FHR, upon entry into the department in the event of spontaneous labor at or beyond 41 weeks; or during the first 20 min of recording of the FHR on the day of induction of labor. FHR recordings were retrospectively analyzed for baseline rate, variability, reactivity, and presence of deceleration, and classified according to the ACOG classification (Supplementary Material 1, www.jcgo.org) into: “normal” (category 1), “indeterminate” (category 2), and “abnormal” (category 3) by the same operator blinded to the perinatal outcomes [5].

All patients were monitored continuously during labor. In those with FHR abnormalities (appearance of late, significant variables or prolonged decelerations), cesarean or operative vaginal delivery were performed, depending of the stage of labor. At birth, neonatal status was evaluated based on clinical examination, neonatal blood gas and need for hospitalization in neonatal intensive care unit.

Women with a “normal” (category 1) admission CTG test were compared to those with an “indeterminate” (category 2) admission CTG test. The primary outcome was the need for emergent cesarean delivery. Secondary outcomes included the presence of neonatal pH < 7.20, neonatal lactates > 5 mmol/L, Apgar score < 7 at 5 min of life, need for operative vaginal delivery and need for hospitalization in neonatal intensive care unit.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The qualitative variables were expressed in n (%) and the quantitative variables in median (minimum - maximum). Chi-squared test or Mann-Whitney test were used when appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine whether an “indeterminate” (category 2) FHR during admission CTG test was predictive of an emergent cesarean delivery during labor, adjusting on gestational age, parity, history of scarred uterus, whether or not an indiction of labor was performed and the indication of emergent cesarean delivery during labor (abnormality of FHR or obstructed labor). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

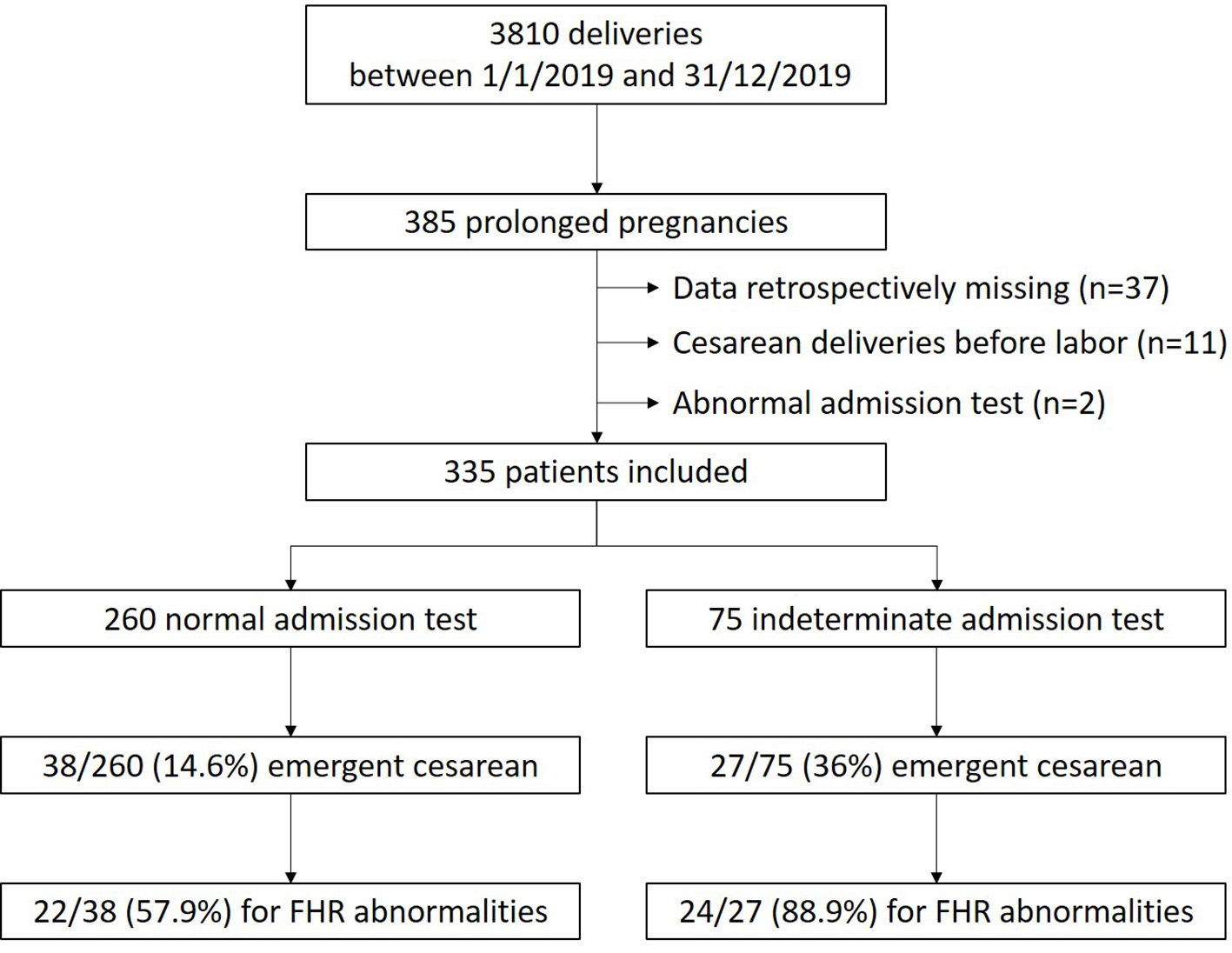

During the study period, 385/3,810 (10.1%) women delivered at or beyond 41 weeks. After excluding 37 women with missing data, 11 women who underwent a pre-labor cesarean delivery and two women with “abnormal” (category 3) FHR during the admission CTG test, our study population included 335 patients: 260/335 (77.6%) presented a “normal” admission CTG test and 75/335 (22.3%) an “indeterminate” admission CTG test (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Study flow chart. |

Demographic and obstetrical characteristics of the women are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference between women with a “normal” and those with an “indeterminate” admission CTG test (Table 1). One hundred fifty-seven out of 335 (46.9%) women underwent an induction of labor: 120/260 (46.2%) in the “normal” group and 37/75 (49.3%) in the “indeterminate” group (P = 0.63).

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of the Cohort: Comparison Between “Normal” and “Indeterminate” FHR During the Admission Cardiotocography Test in Prolonged Pregnancies |

Sixty-five out of 335 (19.4%) emergent cesarean deliveries were performed during labor: 46/65 (70.7%) for abnormal FHR and 19/65 (29.3%) for obstructed labor.

There were significantly more emergent cesarean deliveries in the “indeterminate” group (27/75 (36%)) compared to the “normal” group (38/260 (14.6%), P < 0.01) (Table 2) and significantly more emergent cesarean deliveries for FHR abnormalities in the “indeterminate” group (24/27 (88.9%)) compared to the “normal” group (22/38 (57.9%), P = 0.02).

Click to view | Table 2. Perinatal Outcomes: Comparison Between “Normal” and “Indeterminate” FHR During the Admission Cardiotocography Test in Prolonged Pregnancies |

In case of prolonged pregnancy at or beyond 41 weeks, an “indeterminate” (category 2) admission CTG test increased the risk of emergent cesarean delivery by 3.47 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.8 - 6.5, P < 0.01) adjusted by the gestational age, parity, history of scarred uterus, whether or not an induction of labor was performed and the indication for emergent cesarean delivery (obstructed labor or FHR abnormalities) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 3. Predictors for Emergency Cesarean During Labor in Case With the Observation of a Category 2 Fetal Heat Pattern During the Admission Test in Prologned Pregnancy |

Comparisons of neonatal outcomes between the “normal” and the “indeterminate” admission CTG test groups are presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference among the two groups regarding neonatal outcomes (Table 2).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study demonstrates that an “indeterminate” (category 2) FHR during the admission CTG test for spontaneous labor or induced labor in case of prolonged pregnancies (≥ 41 weeks) increased the risk of emergent cesarean delivery during labor by 3.5 times compared to those with a “normal” (category 1) pattern according to the ACOG classification [5]. This observation suggests that routine evaluation of admission CTG test may have prognostic value, and that this information could potentially help to detect fetuses with high-risk FHR abnormalities during labor in prolonged pregnancies.

The objective of the admission CTG test, first described by Ingemarsson et al [6], was to reduce materno-fetal morbidity [4]. It can be used as a screening test at the time of admission in early labor to detect high-risk fetuses at an increased risk of hypoxia [7] and to select cases who require a continuous electronic fetal monitoring [8]. The admission CTG test is a simple, fast and easily reproducible test that makes it possible to assess the oxygenation and distress of a fetus in early labor. Moreover, admission CTG test assesses the placental reserve by evaluating the response of the fetal heart during the phase of temporary occlusion of the utero-placental blood supply under physiological stress of repeated uterine contractions [6]. It thereby assesses the ability of the fetus to withstand the process of labor.

Detractors of electronic fetal monitoring believe that neonatal outcomes are not significantly improved by the use of admission CTG testing as compared to intermittent FHR auscultation during labor [9]. In a meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of the labor admission CTG test in preventing adverse outcomes, compared with auscultation only, Bix et al concluded that the admission CTG test was not beneficial in low-risk women and did not predict adverse neonatal outcomes [8]. Moreover, they reported that admission CTG test, in low-risk women, was more likely to have minor obstetric intervention such as epidural analgesia, continuous electronic fetal monitoring and fetal blood sampling [8]. Similarly, Rajalekshmi et al evaluated the admission CTG test in 400 women and found a significantly higher rate of cesarean delivery during labor in cases of “suspicious” FHR, compared to the “reassuring” FHR group [10]. Recently, Smith et al conducted a multicenter randomized trial on 3,034 women with low-risk pregnancy who received either admission CTG test or intermittent auscultation and demonstrated no difference in obstetric or neonatal outcomes [11]. However, this concerned only low-risk pregnancies with delivery between 37 and 41 weeks.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the evaluation of the admission CTG test on perinatal outcomes in cases of prolonged pregnancy at our beyond 41 weeks. In a prospective study of 328 high-risk pregnancies, Sharbaf et al [12] reported an increased rate of emergent cesarean delivery for FHR abnormalities when an “intermediate” FHR pattern was found during admission CTG test. However, they only included seven pregnancies > 41 weeks and included high-risk pregnancies (intrauterine growth restriction, maternal hypertension and pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetic mellitus at or beyond 34 weeks).

We acknowledged some limitations, such as the retrospective design of the study and the small number of participants who underwent an emergency cesarean section for fetal distress. Another limitation is that only one individual reviewed and scored the admission CTG tracing.

The use of admission test as a method of routine evaluation of pregnant women is still controversial. Our study supports a role for admission CTG testing in prolonged pregnancy, a high-risk population. An “indeterminate” FHR pattern during admission CTG is likely to predict the need for an emergent cesarean delivery during labor. However, it seems that this test cannot predict fetal outcomes such as low pH, low Apgar score or the need for neonatal resuscitation. Therefore, there are still debates over the effectiveness of this test in predicting the fetal outcomes [13-16]. In some developed countries, the admission test may not have a significant effect in improving the prognosis of infants because women receive continuous antenatal cares. However, in developing countries, this test may be a useful tool [14].

Further studies are needed to determine if the admission CTG test at or beyond 41 weeks could predict neonatal outcomes in cases of expecting management until 41 weeks + 6 days. Moreover, studies are also required to determine convenient supplemental diagnostic modalities that can enhance the positive predictive value of an abnormal admission CTG test. Data obtained from such trials would help in refining the role of admission CTG test in modern day intranatal care.

Conclusion

Admission CTG test is a simple, non-invasive test that can serve as a screening tool in cases of prolonged pregnancy at our beyond 41 weeks to predict whether a fetus is likely to develop fetal distress and may require an emergent cesarean delivery during labor. However, there is scarce evidence to recommend admission CTG test as a screening test to improve neonatal outcomes in cases of prolonged pregnancy.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Fetal Heart Rate (FHR) Interpretation System.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

There is no funding to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been retrospectively obtained.

Author Contributions

AA recruited the patients, managed data and wrote the manuscript. CV performed the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript. GL reviewed the manuscript. PD reviewed the manuscript. RC designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

FHR: fetal heart rate; CTG: cardiotocography; ACOG: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

| References | ▴Top |

- Chantry AA. [Epidemiology of prolonged pregnancy: incidence and maternal morbidity]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2011;40(8):709-716.

doi pubmed - Linder N, Hiersch L, Fridman E, Klinger G, Lubin D, Kouadio F, Melamed N. Post-term pregnancy is an independent risk factor for neonatal morbidity even in low-risk singleton pregnancies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102(4):F286-F290.

doi pubmed - Vayssiere C, Haumonte JB, Chantry A, Coatleven F, Debord MP, Gomez C, Le Ray C, et al. Prolonged and post-term pregnancies: guidelines for clinical practice from the French College of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (CNGOF). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169(1):10-16.

doi pubmed - Blix E, Oian P. Labor admission test: an assessment of the test's value as screening for fetal distress in labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(8):738-743.

doi pubmed - ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 106: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(1):192-202.

doi pubmed - Ingemarsson I, Arulkumaran S, Ingemarsson E, Tambyraja RL, Ratnam SS. Admission test: a screening test for fetal distress in labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;68(6):800-806.

- Khangura K, Chandraharan E. Electronic fetal heart rate monitoring: the future. Current Women's Health Reviews. 2013;9:169-174.

- Bix E, Reiner LM, Klovning A, Oian P. Prognostic value of the labour admission test and its effectiveness compared with auscultation only: a systematic review. BJOG. 2005;112(12):1595-1604.

doi pubmed - Impey L, Reynolds M, MacQuillan K, Gates S, Murphy J, Sheil O. Admission cardiotocography: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9356):465-470.

doi - Rajalekshmi: Admission cardiotocography as a screening - Google Scholar n.d. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Admission%20cardiotocography%20as%20a%20screening%20test%20to%20predict%20foetal%20outcome%20and%20mode%20of%20delivery&journal=Indian%20J%20Obstet%20Gynaecol%20Res&volume=3&issue=1&pages=43-50&publication_year=2016&author=Rajalekshmi%2CM&author=Jayakrishnan%2CC&author=Nithya%2CR. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- Smith V, Begley C, Newell J, Higgins S, Murphy DJ, White MJ, Morrison JJ, et al. Admission cardiotocography versus intermittent auscultation of the fetal heart in low-risk pregnancy during evaluation for possible labour admission - a multicentre randomised trial: the ADCAR trial. BJOG. 2019;126(1):114-121.

doi pubmed - Sharbaf FR, Amjadi N, Alavi A, Akbari S, Forghani F. Normal and indeterminate pattern of fetal cardiotocography in admission test and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(3):694-699.

doi pubmed - Devane D, Lalor JG, Daly S, McGuire W, Cuthbert A, Smith V. Cardiotocography versus intermittent auscultation of fetal heart on admission to labour ward for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1:CD005122.

doi pubmed - Mires G, Williams F, Howie P. Randomised controlled trial of cardiotocography versus Doppler auscultation of fetal heart at admission in labour in low risk obstetric population. BMJ. 2001;322(7300):1457-1460; discussion 1460-1452.

doi pubmed - Sandhu GS, Raju R, Bhattacharyya TK, Shaktivardhan. Admission Cardiotocography Screening of High Risk Obstetric Patients. Med J Armed Forces India. 2008;64(1):43-45.

doi - Elimian A, Lawlor P, Figueroa R, Wiencek V, Garry D, Quirk JG. Intrapartum assessment of fetal well-being: any role for a fetal admission test? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2003;13(6):408-413.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.