| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jcgo.org |

Study Protocol

Volume 12, Number 2, August 2023, pages 59-64

Protocol for a Prospective Cohort Study to Evaluate Changes in Sexuality in Patients With Primary Cervical Cancer Using Patient-Reported Outcomes (JGOG9004, SARAH Study), and Our Approaches to Solving the Unmet Needs of Patients With Gynecological Cancer

Hitomi Sakaia, s, Yoshio Itanib, Yoichi Kobayashic, Mikiko Asai-Satod, Kazuto Tasakie, Shoji Nagaof, Masayuki Futagamig, Makoto Yamamotoh, Etsuko Fujimotoi, Yuji Ikedad, Megumi Yokotaj, Nobutaka Hayashik, Motoki Matsuural, Takayuki Nagasawam, Yumi Ishideran, Shinya Satoo, Tetsutaro Hamanop, Nao Suzukiq, Yoshio Yoshidar

aAdvanced Cancer Translational Research Institute, Showa University, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo142-8555, Japan

bYao Municipal Hospital Palliative Care Center, Yao-city, Osaka 581-0069, Japan

cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Kyorin University, Mitaka-shi, Tokyo 181-8611, Japan

dDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nihon University School of Medicine, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo 173-8610, Japan

eDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kurume University School of Medicine, Kurume, Fukuoka 830-0011, Japan

fDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Okayama University, Kitaku, Okayama 700-8558, Japan

gDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tokyo Medical University Ibaraki Medical Center, Ami-machi, Inashiki-gun, Ibaraki 300-0395, Japan

hJapanese Red Cross Fukui Hospital, Fukui City, Fukui 918-8501, Japan

iDepartment of Gynecologic Oncology, National Hospital Organization Shikoku Cancer Center, Minamiumemotomachi, Matsuyama, Ehime 791-0245, Japan

jDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Keio University School of Medicine, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan

kDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Hyogo 650-0047, Japan

lDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine, Sapporo, Hokkaido 060-8543, Japan

mDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Iwate Medical University School of Medicine, Yahaba-cho, Shiwa-gun, Iwate 028-3695, Japan

nDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine, Kanazawa-Ku, Yokohama City, Kanagawa 236-0004, Japan

oDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tottori University School of Medicine, Yonago 683-8504, Japan

pP4 Statistics Co. Ltd., Setagaya Ku, Tokyo 158-0082, Japan

qDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, St. Marianna University School of Medicine Hospital, Kawasaki City, Kanagawa 216-8511, Japan

rDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Fukui, Eiheiji-cho, Yoshida-gun, Fukui 910-1193, Japan

sCorresponding Author: Hitomi Sakai, Advanced Cancer Translational Research Institute, Showa University, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo142-8555, Japan

Manuscript submitted June 5, 2023, accepted July 15, 2023, published online August 7, 2023

Short title: Sexuality in Cervical Cancer

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo892

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Objective: Sexuality is a crucial quality of life (QOL) issue for patients with cancer. In patients with cervical cancer, sexuality is affected by both the disease and the therapy for it. This study aims to explore changes in sexuality following cancer treatment in Japanese patients with cervical cancer, using scales such as the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) for sexual dysfunction and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for anxiety and depression.

Methods: This multicenter prospective cohort study is being performed in 33 hospitals of the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG), evaluating patients with stage IA - IIIB primary cervical cancer who are scheduled to undergo surgery or radiation therapy, including concurrent chemoradiation, with curative intent. Patients can visit the uniform resource locator (URL) listed in the email to complete the survey. The online survey is performed at baseline and at 1 year following curative surgery or radiation therapy. As of March 31, 2023, 200 participants have been recruited for this ongoing study.

Discussion: The results of this study are expected to highlight sexuality as an unmet need among patients with cervical cancer. Conducting the study may facilitate discussions between patients and healthcare providers regarding sexual issues.

Keywords: Cervical cancer; Sexual health; Female sexual dysfunction

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Sexuality is a quality of life (QOL) issue for many patients with cancer [1]. According to the World Health Organization, healthy sexuality is not only the absence of sickness, dysfunction, or infirmity, but also a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being [2]. Sexuality is a multidimensional construct comprising the physiological, psychological, and social dimensions of sex. Sexual dysfunction occurs during the sexual response cycle [3]. Over 50% and, by some reports, as many as 90% of patients with gynecological cancers experience sexual dysfunction [4, 5].

Gynecological cancer treatment affects sexual function. Radical hysterectomy shortens the vagina, and surgical removal of both ovaries causes ovarian dysfunction [6, 7]. Ovarian dysfunction can lead to decreased vaginal lubrication and vaginal mucosal atrophy, causing pain during sexual intercourse. Irradiation of the pelvic region can cause narrowing of the vagina due to scarring, as well as decreased vaginal lubrication, resulting in pain during sexual intercourse and difficulty during sexual penetration [8]. Radiation therapy causes varying degrees of ovarian dysfunction, depending on the radiation dose and age of the patient [9]. Chemotherapy causes systemic symptoms such as fatigue and may decrease libido. Chemotherapy can also cause transient or permanent ovarian dysfunction. Moreover, cancer and cancer treatments have psychological effects. Loss of sexual interest [10], psychosexual distress [11], body image disturbance [12], and depression [13] have been reported in patients with gynecological cancers. The degree of sexual dysfunction varies significantly from patient to patient, even with the same treatment.

The evaluation of sexual dysfunction in women is complex. The frequency of sexual intercourse is only one aspect of sexuality. The female sexual response is complex and is more difficult to assess objectively than in men, being related to factors such as sexual desire, sexual sensation, orgasm, pain, and satisfaction. The evaluation of female sexual dysfunction requires both a physical and psychological approach, keeping in mind its differences from male sexuality. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (2013) classifies female sexual dysfunction as “female sexual interest/arousal disorder”, “female orgasmic disorder”, and “genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder”. Female sexual dysfunction is classified as lifelong, acquired, generalized, or situational [14]. Its etiology is further classified as organic, psychogenic, mixed, or unknown. Several scales have been developed to assess female sexual dysfunction, including the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), a Japanese version of which has been psychometrically validated for reliability and validity [15].

Few published studies to date have compared pre-and post-treatment female sexual function in patients with cancer [16], and most have only evaluated it at a single point during or after treatment [17, 18]. However, we speculate that there are inherent individual differences in sexual function, and that there are also individual differences in whether or not one considers sexual activity with a partner to be necessary. Therefore, we believe that a baseline assessment is also necessary. This study compares pre- and post-treatment sexuality in patients with cervical cancer. Cultural and social factors may also impact sexuality. To date, no quantitative study of Japanese patients with gynecological cancers has addressed the relationship between changes in sexuality and psychological distress following treatment.

Although clinical cancer guidelines state that healthcare providers should discuss sexual health issues with their patients [19], these conversations rarely occur. This may be due to a number of reasons, including insufficient time, avoidance of sexual health discussion due to cultural backgrounds, and shyness in patients with regard to reporting their symptoms.

The fourth-term Basic Plan to Promote Cancer Control Programs in Japan (Cabinet Decision on March 28, 2023) does not address sexual health issues, although it mentions fertility preservation and appearance care, which are both closely related to sexual health issues. Therefore, clinicians should take measures to identify and clarify the actual conditions surrounding the unmet needs of cancer patients in Japan. This study highlights sexual health issues, which represent an underappreciated need in patients with cancer. To encourage more honest responses and reduce social desirability bias, we conducted a email-based online survey and collected patient-reported outcomes directly from patients.

Objective

Primary objective

The primary objective of this study is to explore changes in sexuality following cancer treatment in patients with cervical cancer, using scales such as the FSFI for sexual dysfunction and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for anxiety and depression.

Secondary objective

Our secondary objective is to identify the factors associated with sexual dysfunction following treatment in patients with primary cervical cancer.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and situation

This multicenter prospective cohort study is being performed across 33 hospitals of the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG). The JGOG is a clinical research group that works with major universities and cancer centers throughout the country to establish the latest and most suitable diagnostic and therapeutic methods for patients with gynecologic malignancies. Because it is not possible to establish a no-treatment control, this is a single-arm cohort study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards and the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Boards of each institution approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Institutional Review Board statement

The study protocol was approved by the JGOG Clinical Trial Review and Ethics Committee (protocol code: JGOG 9004), Kindai University Clinical Research Review Board (30-111), and the review boards of the participating institutions. The trial was registered at the UMIN-CTR (UMIN000033641).

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included: 1) histologically confirmed cervical cancer; 2) diagnosed with cervical cancer within 3 months prior to enrollment; 3) the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification (FIGO 2008), stage IA - IIIB; 4) the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) 0 - 1 at the time of consent; 5) at least 20 years old and 70 years old or less at the time of consent; 6) has a partner at the time of consent, and partners include married or de facto spouses and lovers; 7) scheduled for surgery or radiation (including chemoradiotherapy) with curative intent within 2 months of registration; 8) the individual’s consent to participate in the study has been obtained in writing.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included patient who: 1) has mental illness; 2) is pregnant; 3) has conditions that would make the patient inappropriate for participation in this study, according to the investigator’s judgment.

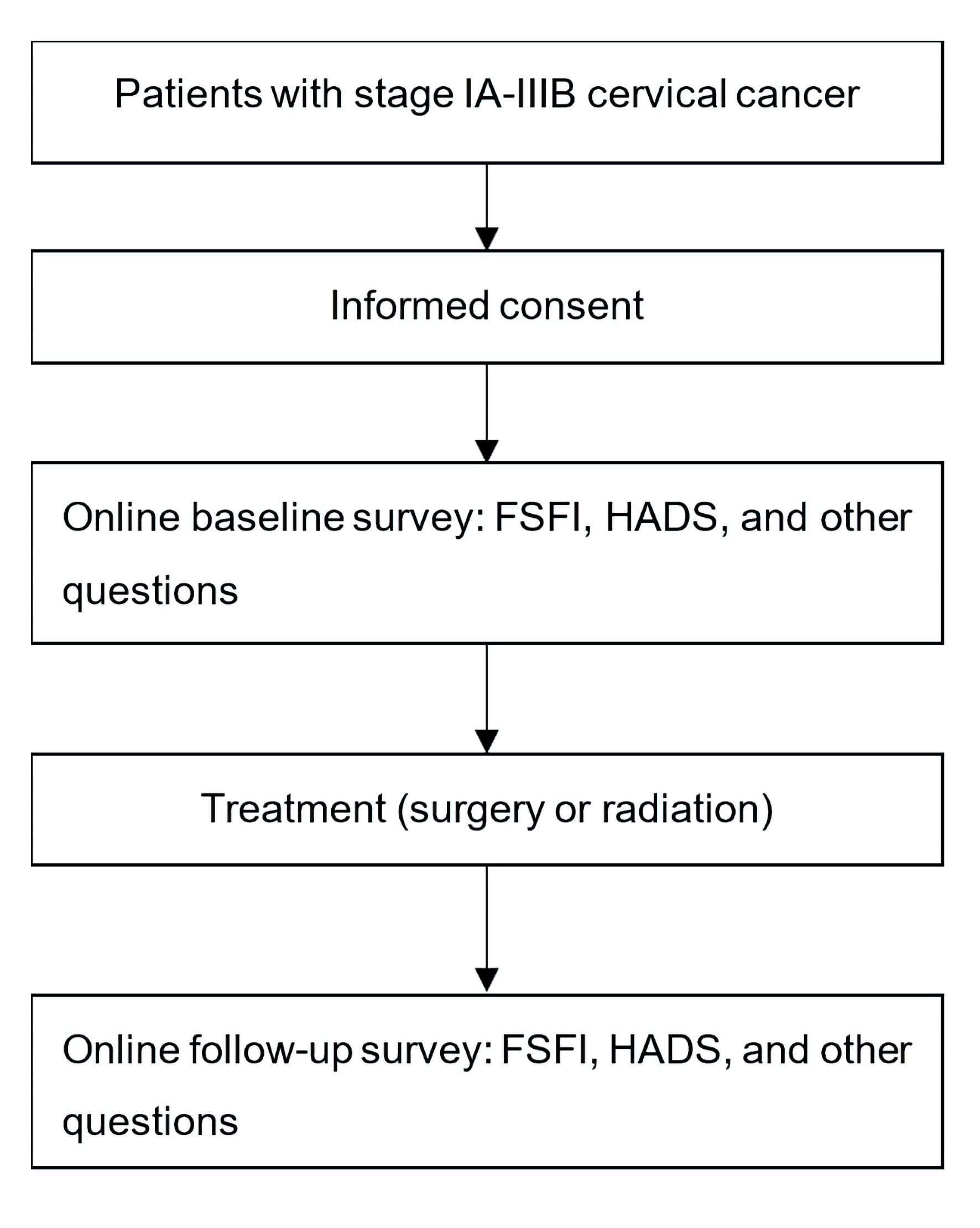

Study procedure

The site investigators collected the data through web-based self-reported questionnaires filled out by the patients, as well as case report forms (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Study schema of SARAH study (JGOG 9004). FSFI: Female Sexual Function Index; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; JGOG: the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group. |

Survey items

Baseline survey for patients

Baseline survey for patients included: 1) number of children; 2) occupation (full-time job, part-time job, self-employed, unemployed, student, other); 3) educational background (junior high school, high school, junior college/technical college, university/graduate school); 4) menstrual status (premenopausal/postmenopausal/unknown); 5) FSFI; 6) sexual activity with a partner in the past 3 months (presence, absence); 7) frequency of sexual intercourse (once in 3 months, once in 1 month, once in 2 weeks, once in 1 week, none); 8) importance of sexual intercourse (unimportant, slightly important, moderately important, important, very important); 9) the presence of physical affection other than sexual intercourse in the past 3 months (presence, absence); 10) importance of physical affection other than sexual intercourse (unimportant, slightly important, moderately important, important, very important); 11) HADS.

Follow-up survey for patients

Follow-up survey for patients included: 1) change in partnership (divorced, ongoing); 2) FSFI; 3) sexual activity with a partner in the past 3 months (presence, absence); 4) frequency of sexual intercourse (once in 3 months, once in 1 month, once in 2 weeks, once in 1 week, none); 5) importance of sexual intercourse (unimportant, slightly important, moderately important, important, very important); 6) the presence of physical affection other than sexual intercourse in the past 3 months (presence, absence); 7) importance of physical affection other than sexual intercourse (unimportant, slightly important, moderately important, important, very important); 8) HADS.

Patient characteristics at baseline

Patient characteristics at baseline included: 1) date of birth; 2) ECOG performance status; 3) clinical stage; 4) scheduled start date of treatment; 5) disease status (during or after preoperative chemotherapy).

Disease and treatment history

Disease and treatment history included: 1) histology of the disease (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, other); 2) treatment (surgery, surgery and radiation, surgery and chemotherapy, surgery and chemoradiation, chemoradiation, radiation, other); 3) surgical procedure/date (conization, abdominal total hysterectomy, laparoscopic total hysterectomy, abdominal modified radical hysterectomy, laparoscopic modified radical hysterectomy, abdominal radical hysterectomy, laparoscopic radical hysterectomy, abdominal radical trachelectomy, other); 4) bilateral oophorectomy (performed, not performed); 5) ovarian transposition (performed, not performed); 6) radiation method/date (external or internal).

Data management

CSM (Tokyo, Japan) has been commissioned by JGOG to perform data center operations. The data center conducts registration and data collection. The JGOG Clinical Trial Review and Ethics Committee assesses all protocol amendments and provides the necessary recommendations to the study investigators. CSM and JGOG monitor patient enrollment and response status. The JGOG conducts audits as necessary for this study.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint

Primary endpoint is the FSFI scores for sexual dysfunction [15]. From the answers to the 19-item FSFI questionnaire, the FSFI total score and total score for each of the six domains are calculated according to the standard FSFI evaluation method. The primary endpoint is the total FSFI score. We will evaluate changes at 12 months following the initiation of treatment, compared to the baseline.

Secondary endpoints

Secondary endpoints included: 1) the presence/absence, frequency, and importance of sexual intercourse, and the presence/absence and importance of physical affection other than sexual intercourse; 2) changes at 12 months following the start of treatment, compared to the baseline; 3) scores for anxiety and depression using the HADS [20] (from the responses to the 14-item HADS questionnaire, the total HADS score and depression/anxiety scores will be calculated according to the standard assessment method for HADS); 4) changes at 12 months following the initiation of treatment, compared to the baseline.

Statistical analysis

The target number of cases is based on the number of cases that can be registered in actual clinical practice in Japan and is not set by statistical methodology. A total of 6,600 cervical cancer cases (FIGO clinical advanced stage classification IA - IIIB) for whom treatment was initiated between January 1 and December 31, 2014, were registered by 411 member institutions of the Japanese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Of these patients, 5,533 (84%) were between 20 and 69 years of age [21]. Assuming that 30 centers participate in the study and distribute the baseline questionnaire to all patients, approximately 404 cases will be distributed in 1 year, and 606 cases will be distributed in 1.5 years. Assuming a collection rate of 50%, 202 cases will be collected in the first year, and 303 cases in the first 1.5 years. Assuming a 50% collection rate for the follow-up survey, the target number of cases was set at 150 (FIGO clinical advanced stage classification IA to IIIB) and the enrollment period at 1.5 years.

Based on the results of a questionnaire survey [18] for stage IB and II cervical cancer patients who underwent radiation therapy or radical surgery and non-cervical cancer patients in Japan, it was deemed that the FSFI total scores in the treated patients followed a non-normal distribution.

Therefore, we will estimate the median and the interquartile range of the change of total FSFI scores, and the Wilcoxon signed rank test will be used for the primary analysis, with a null hypothesis that the change of total FSFI scores = 0, at a two-sided significance level of 0.05. A mixed model for repeated measure (MMRM) will also be used with the Kenward-Roger adjustment method for supportive analyses. The least-squares mean changes from baseline in total FSFI scores at 12 months and their 95% confidence intervals will be estimated. We will perform the same analyses for patients who underwent radical surgery and those who received radiation therapy on each.

Trial status

The trial began in September 2018, and 200 subjects were enrolled by March 31, 2023. Recruitment was stopped in March 2023. The follow-up period is ongoing.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In the SARAH study (JGOG9004), we highlight sexual health issues as an unmet need among patients with cervical cancer. There is currently limited data and knowledge regarding sexual health issues among Japanese patients with gynecological cancers. This study increases public awareness of these issues associated with cancer treatment.

Conducting this study may encourage discussions between patients and healthcare providers regarding sexual issues. The Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT) model, a counseling framework used to help healthcare providers address their patients’ sexual health issues, suggests that the first step is to give permission to the patient to discuss their sexual concerns [22]. Therefore, explaining and discussing this study may represent an initial step toward implementing the PLISSIT model.

The data obtained from this study will hopefully form a foundation for future studies to develop supportive measures for sexual health issues, not only in patients with cervical cancer but also in those with other cancer types. The study will be dedicated to solving and supporting sexual health issues, which represent significant unmet needs among patients with cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants, their families, and the investigators involved in this study. We also thank Eisuke Tsuchihashi at CSM for his support with data collection, and Hitoshi Sawada at JGOG for his support in study management.

Financial Disclosure

This study was supported by the Project Mirai Cancer Research Grant 2021.

Conflict of Interest

HS received grants to her institution from Eisai and lecture fees from Daiichi Sankyo and Eisai outside the submitted work. TH received lecture fees from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: all authors. Methodology: HS. Writing - original draft preparation: HS. Data acquisition: Y. Itani, YK, MAS, KT, SN, MF, MY, EF, Y. Ikeda, MY, NH, MM, TN, Y. Ishidera, SS, NS, and YY. Statistical analysis: TH. Supervision: NS and YY. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request following the publication of the study results.

Abbreviations

QOL: quality of life; FSFI: the Female Sexual Function Index; HADS: the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; JGOG: the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group

| References | ▴Top |

- Abbott-Anderson K, Kwekkeboom KL. A systematic review of sexual concerns reported by gynecological cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):477-489.

doi pubmed - WHO: World Health Organization. Defining Sexual Health. 2006.

- American College of Obstetricians, Gynecologists' Committee on Practice. Bulletins-Gynecology. Female sexual dysfunction: ACOG practice bulletin clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, Number 213. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(1):e1-e18.

doi pubmed - Krychman ML, Pereira L, Carter J, Amsterdam A. Sexual oncology: sexual health issues in women with cancer. Oncology. 2006;71(1-2):18-25.

doi pubmed - Onujiogu N, Johnson T, Seo S, Mijal K, Rash J, Seaborne L, Rose S, et al. Survivors of endometrial cancer: who is at risk for sexual dysfunction? Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123(2):356-359.

doi pubmed - Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1383-1389.

doi pubmed - Pieterse QD, Maas CP, ter Kuile MM, Lowik M, van Eijkeren MA, Trimbos JB, Kenter GG. An observational longitudinal study to evaluate miction, defecation, and sexual function after radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(3):1119-1129.

doi pubmed - Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56(4):937-949.

doi pubmed - Yin L, Lu S, Zhu J, Zhang W, Ke G. Ovarian transposition before radiotherapy in cervical cancer patients: functional outcome and the adequate dose constraint. Radiat Oncol. 2019;14(1):100.

doi pubmed pmc - Greimel ER, Winter R, Kapp KS, Haas J. Quality of life and sexual functioning after cervical cancer treatment: a long-term follow-up study. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):476-482.

doi pubmed - Classen CC, Chivers ML, Urowitz S, Barbera L, Wiljer D, O'Rinn S, Ferguson SE. Psychosexual distress in women with gynecologic cancer: a feasibility study of an online support group. Psychooncology. 2013;22(4):930-935.

doi pubmed - Teo I, Cheung YB, Lim TYK, Namuduri RP, Long V, Tewani K. The relationship between symptom prevalence, body image, and quality of life in Asian gynecologic cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):69-74.

doi pubmed - Bae H, Park H. Sexual function, depression, and quality of life in patients with cervical cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(3):1277-1283.

doi pubmed - Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 2013

- Takahashi M, Inokuchi T, Watanabe C, Saito T, Kai I. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): development of a Japanese version. J Sex Med. 2011;8(8):2246-2254.

doi pubmed - Carter J, Sonoda Y, Baser RE, Raviv L, Chi DS, Barakat RR, Iasonos A, et al. A 2-year prospective study assessing the emotional, sexual, and quality of life concerns of women undergoing radical trachelectomy versus radical hysterectomy for treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(2):358-365.

doi pubmed pmc - Kulkarni A, Sun G, Manuppelli S, Mendez H, Rezendes J, Marin C, Raker CA, et al. Sexual health and function among patients receiving systemic therapy for primary gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;165(2):323-329.

doi pubmed - Harding Y, Ooyama T, Nakamoto T, Wakayama A, Kudaka W, Inamine M, Nagai Y, et al. Radiotherapy- or radical surgery-induced female sexual morbidity in stages IB and II cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(4):800-805.

doi pubmed - Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, Barton DL, Bolte S, Damast S, Diefenbach MA, et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(5):492-511.

doi pubmed - Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

doi pubmed - Nagase S, Ohta T, Takahashi F, Yaegashi N. Annual report of the Committee on Gynecologic Oncology, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Annual patient report for 2017 and annual treatment report for 2012. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2021;47(5):1631-1642.

doi pubmed - Annon JS. The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. Journal of sex education and therapy 1976, 2(1):1-15.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.