| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Original Article

Volume 4, Number 1, March 2015, pages 160-163

Outcomes of Triplets Reduced to Twins Versus Non-Reduced Triplet Pregnancies

Donna B. Ravala, b, e, Mary Naglakc, Sara N. Iqbala, Patrick S. Ramseya, Frank Craparod

aMaternal-Fetal Medicine Section, Department of Women’s, Infants, and Children, Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC, USA

bNational Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

cDepartment of Medicine, Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, PA, USA

dDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington, PA, USA

eCorresponding Author: Donna B. Raval, National Institutes of Health, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bldg 10, 3c710, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication March 25, 2015

Short title: Triplet Pregnancies

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jcgo322w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: This study examined the outcomes of triplet pregnancies selectively reduced to twin pregnancies, compared with non-reduced triplet pregnancies using a standardized approach.

Methods: This study is an observational retrospective study of all women who presented to the Fetal Diagnostic Center between 1999 and 2009, had triplet pregnancies in the first trimester, received prenatal care and delivered at Abington Memorial Hospital. Data analysis was performed with SPPS version 15 for Windows using analysis of variance and Fisher’s exact test.

Results: One hundred thirty-two triplet pregnancies were identified. In the reduced group (n = 30) compared to the non-reduced triplet group (n = 102), average gestational age of delivery was longer 34.6 weeks versus 31.2 weeks gestation (P ≤ 0.0005) and days in hospital were less 9.0 versus 26.7 days (P = 0.001). There was a significantly lower incidence of gestational diabetes and preterm labor in reduced pregnancies. Rate of loss, defined as delivery less than 24 weeks, was similar (3.3% versus 4.9%).

Conclusion: Women electing to reduce a triplet pregnancy to twins have higher gestational ages at delivery, lower rates of gestational diabetes and preterm labor, and spend fewer days in hospital than non-reduced triplet pregnancies.

Keywords: Triplets; Multifetal pregnancy reduction; Twins

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The management and counseling of triplet pregnancies remains an area of controversy in obstetrics [1]. Higher order multiple pregnancies have increased with the increasing use of artificial reproductive techniques [2]. Triplet pregnancies are at increased risk of both maternal and fetal complications including pregnancy loss, nearly 100% preterm delivery rates, and increased rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia compared to twin and singleton pregnancies. Because of the high-risk nature of the pregnancy, women are often offered multifetal pregnancy reduction (MFPR).

MFPR is a procedure that was created in the 1980s. Since then many practitioners have gained experience, in theory lowering the complication rates of the procedure itself. Practitioners caring for patients with triplet pregnancies and patients faced with the decision of MFPR or expectantly managing a triplet pregnancy have conflicting literature to base their decision and counseling on [3-6]. MFPR has been shown to improve outcomes of patients with quadruplets or higher in the literature [4]. The largest series in the literature has over 1,000 cases of MFPR; however, it assessed the outcomes of twins, triplets, and higher order multiples undergoing MFPR [7], with the best outcomes occurring in twins reduced to singletons with lower loss rates. As stated in the Cochrane review in 2012, there are no randomized controlled trials comparing the outcomes and embarking upon that study would be very difficult with patient recruitment [8].

Our objective was to compare the outcomes of triplet pregnancies reduced to twins compared to non-reduced triplet pregnancies.

| Material and Methods | ▴Top |

This is an observational retrospective study of all women who presented to the Fetal Diagnostic Center (FDC) between 1999 and 2009 who were found to have triplet pregnancies in the first trimester, received prenatal care, and then delivered at Abington Memorial Hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board. All women with triplet pregnancies were offered multifetal reduction. Only women electing to either expectantly manage their triplet pregnancy or women electing to reduce to a twin pregnancy were included. Any woman who reduced to a singleton pregnancy was excluded from analysis.

Women with a triplet pregnancy were identified in the computerized system using the appropriate ultrasound codes for triplet pregnancies and MFPR. Data collected from obstetric records included maternal demographics (age, gravidity, and parity) as well as pregnancy complications (preterm delivery, preterm premature rupture of membranes, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, etc.). The Maternal-Fetal Medicine Group at Abington Memorial Hospital counseled all patients. FC performed all of the procedures via transabdominal intrathoracic injection of potassium chloride. All patients were offered nuchal translucency and CVS at the time of counseling. Women had CVS and/or nuchal translucency performed with results prior to MFPR. The procedure was performed between 10 and 14 weeks.

Pregnancy loss was defined as delivery prior to 24 weeks. Various parameters were collected including: gestational age at delivery, number of days in the hospital, rates of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes, birth weight, and Apgar score. Patients were considered to be treated for preterm labor if they received any tocolytic or combination thereof. The number of days in the hospital is an aggregate of both antepartum and postpartum hospitalizations.

Data analysis was performed with SPPS version 15.0 with computation of 95% confidence intervals. Tests performed included descriptive statistics including means and frequencies and inferential statistics including Fisher’s exact test, odds ratios (OR), and analysis of variance. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

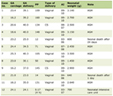

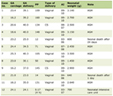

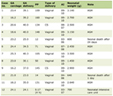

One hundred thirty-two triplet pregnancies were identified that fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Thirty patients opted for MFPR to a twin pregnancy and 102 patients opted to expectantly manage their triplet pregnancy (Table 1). The reduced triplet pregnancy group delivered at a significantly later average gestational age (34.6 weeks) versus the non-reduced triplet pregnancy group (31.2 weeks, P ≤ 0.0005) using ANOVA (Table 2). Maternal days in the hospital were significantly decreased for reduced triplet pregnancies compared to non-reduced triplet pregnancies (9.0 days, 95% CI: 4.7 - 13.4 vs. 26.7 days, 95% CI: 21.4 - 32.0, P = 0.001) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 1. Maternal Characteristics by MFPR Category |

Click to view | Table 2. Neonatal Characteristics by MFPR Category |

Click to view | Table 3. Maternal Outcomes by MFPR Category |

There was a significant reduction in the incidence of gestational diabetes and preterm labor in non-reduced triplet pregnancies versus reduced (22.5% versus 3% patients with gestational diabetes (OR = 8.4 for non-reduced triplets, 95% CI: 1.1 - 65.4, P = 0.015)), and (60.8% versus 30% (OR = 3.6 for non-reduced triplets, 95% CI: 1.5 - 8.7, P = 0.004)) patients treated for preterm labor.

There was no difference in the rates of preeclampsia, preterm premature rupture of membranes, cervical insufficiency and/or cerclage placement, clinical chorioamnionitis or abruption. Pregnancy loss defined as delivery less than 24 weeks was similar between the two groups, 3.3% in reduced versus 4.9% in non-reduced triplets. There was no association found between non-reduced triplets and reduced triplets for either the 1 or 5 min Apgar scores (not shown).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Expectant management of a high order pregnancy is associated with inherent fetal problems related to preterm birth, low birth weight, survival, and long term morbidity. Reduction in the number of fetuses has been suggested to reduce the adverse neonatal outcomes although this has been widely debated.

Women in our study electing to reduce a triplet pregnancy to twins had higher gestational ages at delivery, lower rates of gestational diabetes and preterm labor, and spent fewer days in hospital than patients electing to expectantly manage triplet pregnancies. MFPR has no significant impact on early pregnancy loss. This is in comparison to prior studies that have either shown no effect on gestational age at delivery or a decrease in preterm birth rate but a higher early pregnancy loss rate [9].

A significant difference in gestational age at delivery was seen in our groups. Both groups had many preterm deliveries. Reduced triplets had higher gestational ages overall with more reaching full term than non-reduced triplet pregnancies. Days spent in the hospital were chosen as a surrogate for maternal morbidity encompassing a significant antepartum hospitalization time for triplet pregnancies. For patients who have MFPR, they spent less time in the hospital compared to triplet pregnancies. Aside from more office visits, ultrasounds, and evaluation, spending a significant more time in the hospital can be an important counseling point to patients especially if they have children at home.

Strengths of this study include the counseling and management of the triplet pregnancies was in a standardized method and all of the pregnancies entered care at a similar gestational age. In this institute, one provider performed all of the procedures.

In one study of 127 triplet pregnancies, there was no difference in gestational age at delivery or live birth rate noted [6] while our study demonstrated a significant difference in gestational age at birth. The study by Yaron et al demonstrated a difference in gestational age at delivery with lower miscarriage rates in the reduced group [5]. The stated pregnancy loss rate of 25% in this study is much higher than seen in our study, which had a pregnancy loss rate of 4.9% for non-reduced triplets. In the study by Stone et al, there was a similar loss rate as our study. This study was completed in three different institutions as well as had starting fetal numbers of two to more than five [7].

Haas and colleagues compared reduced triplets to twins using a transvaginal reduction approach to expectantly managed twins which is a different approach than the majority of studies; they concluded these two groups have similar outcomes [10]. A recent study from the Netherlands compared trichorionic triplet pregnancies reduced to twins with expectantly managed triplets and twin pregnancies [11]. This study concluded that reduction increases gestational age at birth by 3 weeks but does not improve the fetal outcome [11]. This study is limited by the low numbers of continuing triplets, 44 versus 86 reduced triplets.

Directions for future research include continuing to increase the experience with reduced and non-reduced triplets. With improving neonatal care and management of obstetric complications, this issue will need to be continuously studied and updated to adequately counsel patients.

Sources of Support

No sources of support or grants for this study were received.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest by the authors to declare.

Author Note

This abstract was presented at the 2012 SMFM, The Pregnancy Meeting in Dallas, TX.

| References | ▴Top |

- Evans MI, Britt DW. Multifetal pregnancy reduction: evolution of the ethical arguments. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(4):295-302.

doi pubmed - ACOG Committee opinion no. 553: multifetal pregnancy reduction. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(2 Pt 1):405-410.

pubmed - Smith-Levitin M, Kowalik A, Birnholz J, Skupski DW, Hutson JM, Chervenak FA, Rosenwaks Z. Selective reduction of multifetal pregnancies to twins improves outcome over nonreduced triplet gestations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(4 Pt 1):878-882.

doi - Fasouliotis SJ, Schenker JG. Multifetal pregnancy reduction: a review of the world results for the period 1993-1996. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;75(2):183-190.

doi - Yaron Y, Bryant-Greenwood PK, Dave N, Moldenhauer JS, Kramer RL, Johnson MP, Evans MI. Multifetal pregnancy reductions of triplets to twins: comparison with nonreduced triplets and twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(5):1268-1271.

doi - Leondires MP, Ernst SD, Miller BT, Scott RT, Jr. Triplets: outcomes of expectant management versus multifetal reduction for 127 pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(2):454-459.

doi pubmed - Stone J, Ferrara L, Kamrath J, Getrajdman J, Berkowitz R, Moshier E, Eddleman K. Contemporary outcomes with the latest 1000 cases of multifetal pregnancy reduction (MPR). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(4):406 e401-404.

- Dodd JM, Crowther CA. Reduction of the number of fetuses for women with a multiple pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD003932.

doi - Papageorghiou AT, Avgidou K, Bakoulas V, Sebire NJ, Nicolaides KH. Risks of miscarriage and early preterm birth in trichorionic triplet pregnancies with embryo reduction versus expectant management: new data and systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(7):1912-1917.

doi pubmed - Haas J, Hourvitz A, Dor J, et al. Perinatal outcome of twin pregnancies after early transvaginal multifetal pregnancy reductions. Fertility and Sterility. 2014;0015-0282.

- van de Mheen L, Everwijn SM, Knapen MF, Oepkes D, Engels M, Manten GT, Zondervan H, et al. The effectiveness of multifetal pregnancy reduction in trichorionic triplet gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(5):536 e531-536.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.