| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.jcgo.org |

Case Report

Volume 1, Number 2-3, June 2012, pages 49-52

Unusual Cause of Uterine Perforation Secondary to Methylene Blue Chromopertubation After Hysteroscopic Septum Resection

Murat Apia, Hakan Nazika, b, Hakan Aytana, Raziye Narina

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, Turkey

bCorresponding author: Hakan Nazik

Manuscript accepted for publication February 14, 2012

Short title: Cause of Uterine Perforation Secondary

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jcgo5w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

In the present case uterine perforation during the laparoscopic tubal passage control after hysteroscopic resection of septum is presented. Hysteroscopic septum resection by monopolar loop resectoscope was performed after laparoscopic confirmation of the diagnosis of a septate uterus in a 27 year old, gravida 1, spontaneous abortion 1 woman. The vaginal septum was resected safely. When chromopertubation was done with methylene blue under laparoscopic control, the uterus was perforated. The perforation was sutured by laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing. Performing choromolaparoscopy after hysteroscopic resection of uterine septa may cause uterine perforation. Hemorrhage from the perforation can be managed by laparoscopic intracorpereal suturing.

Keywords: Uterine perforation; Septate uterus; Chromolaparoscopy; Hysteroscopy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Uterine septum is reported to be the most common congenital anomaly of the female reproductive tract, with an incidence of 80 - 90% of all major malformations both in women with recurrent pregnancy loss and in the general population [1, 2].

Operative hysteroscopy, to avoid the risks of open surgery, has become the standard treatment for uterine septa. Uterine perforation is the most common complication of hysteroscopy. In most studies, hysteroscopy is complicated by confirmed uterine perforation in 0.8 to 1.6% of operative procedures [3-6]. The perforation rate is less during diagnostic hysteroscopy (eg, 0.1 versus 1% with operative hysteroscopy in a series of 13,600 procedures) [4].

The aim of the present case report is to demontrate an unusual cause of uterine perforation due to methylene blue dye control for tubal patency after hysteroscopic resection of uterine septum. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no published data related to the uterine perforation at the time of methylene blue control for tubal patency.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 27-year-old, gravida 1, spontaneous abortion 1, woman with a mullerian anomaly at hysterosalpingography (HSG) with a complaint of chronic dysmenorhoea and desire of pregnancy was admitted to the hospital. She had been married for 1.5 years. She concieved naturally at the end of the first year, but she miscarried at her 8th weeks of gestation. During her first vizit after the abortion, a septate uterine anomaly as the possible cause of her miscarriage was suspected with an ultrasonographic examination. HSG was scheduled.

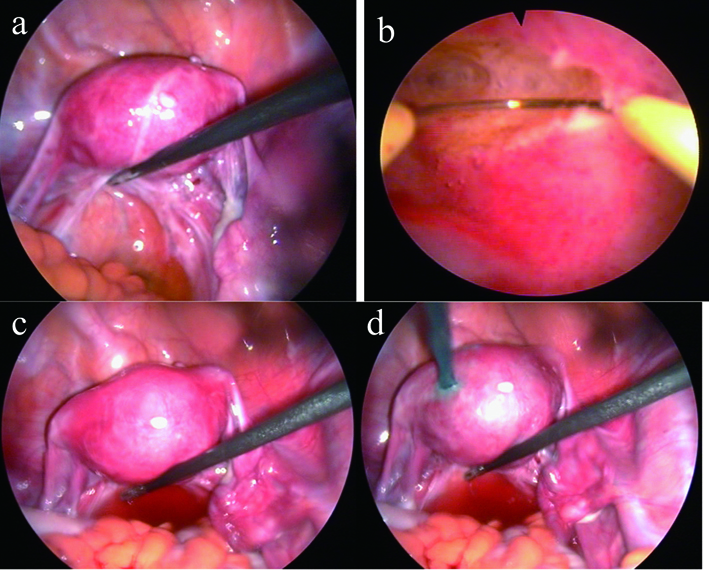

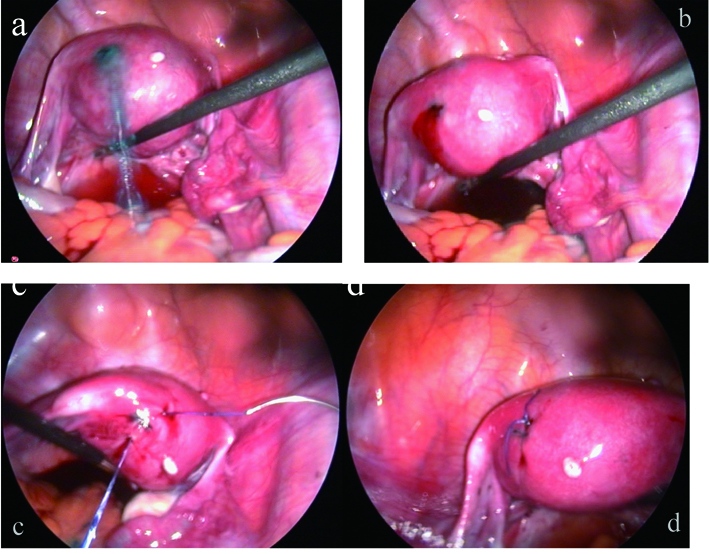

The hysterosalpingographic appearence of the patient’s uterus is shown in Figure 1. With this appearance the radiologist reported a bicornuate uterus; however, as gynecologists we thought this to be a septate uterus. Therefore, laparoscopic approach was needed to confirm the diaognosis of this Mullerian anomaly. At three port standart laparoscopy, the uterine fundus was in dome shape confirming that the uterus was not bicornuate (Fig. 2a). While the laparoscopic ports were left in situ, hysteroscopy was initiated. No pretreatment was used in order to ease cervical dilatation or endometrial visualization. Rigid Hegar dilatators up to #9.5 was applied before the rigid 8 mm operative hysteroscope (RZ-Medizintechnik GmbH) was inserted into the uterine cavity. In hysteroscopy, 300 optic was used. For operative procedure a monopolar electrosurgical instrument (wire loop) and 1.5% glycine as distention media were used. The uterine septum was visualized and cut with monopolar current (40 watts) (Fig. 2b). Both tubal ostia were visualized without complication. We decided to control the tubal passage by laparoscopy and intact dome shaped uterine fundus was confirmed again (Fig. 2c). Although the distension media seen in the Douglas pouch suggested the tubal passage, we decided to confirm the tubal patency by chromolaparoscopy with the aid of an intrauterine foley catheter without balloon instillation. At first attempt, intrauterine methylene blue leaked out from the cervix, so the balloon was instilled with 10 ml of saline. The methylene blue was instilled again under the direct visualization by laparoscope and the uterine fundus was perforated by the pressure of methylene blue (Fig. 2d). Concomitantly, tubal passage was also confirmed. Dye pressure caused a 1cm perforation at left uterine fundal region (Fig. 3a). The site of perforation was observed and some pressure by the laparoscopic instrument was applied however, the bleeding could not be controlled by this conservative measure (Fig. 3b). Laparoscopic intarcorporeal U suture was performed to control hemorrhage (Fig. 3c, d). The patient discharged at first postoperative day without any compolication. At the postoperative 7th day visit, sonography revealed no residual septum.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Hysterosalpingography of the patient before the operation. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. a: Dome shaped uterine fundus before septum resection b:Hysteroscopic septum resection c: Intact uterine fundus after the septum resection d: Perforation of the uterus by pressure of methylene blue dye. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. a: Uterine perforation from the fundus b: Bleeding from the perforation site c and d: Intracorporeal suture to control the bleeding and restore the uterine wall integrity. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Failure of absorption of the partition between the two fused mullerian ducts results in a septum that divides the uterine cavity; the external appearance remains that of a single uterus. The extent of the septum varies: it might be partial, involving part of the uterine cavity, or so complete as to divide both the uterine cavity and endocervical canal into two equal or unequal components [7].In a recent series by Faivre et al. a septate uterus was diagnosed with 3-D ultrasonography in 29 patients and bicornuate uterus in 2 patients. Hysteroscopic transcervical section of the uterine septum was achieved in the 29 patients. Bicornuate uterus was laparoscopically confirmed in the 2 patients. Concordance between ultrasonography and operative hysteroscopy or laparoscopy was verified in all 31 cases. Twenty-five uterine septa and 5 bicornuate uteri were diagnosed by hysteroscopy (3 false-positive diagnoses of bicornuate uterus, 1 unfeasible hysteroscopy). Hysteroscopic diagnosis was correct in 27/30 patients. Twenty-four septate uteri and 7 bicornuate uteri were diagnosed by MRI (5 false-positive diagnoses of bicornuate uterus). Two complete septate uteri diagnosed by MRI were finally confirmed as incomplete septate uteri after 3-D ultrasonography and operative hysteroscopy. MRI diagnosis was correct in 24/31 patients [8]. HSG does not evaluate the external contour of the uterus and therefore it cannot reliably differentiate between a septate and a bicornuate uterus [9-11]. Some authors suggest that an angle of < 75° between the uterine horns is suggestive of a septate uterus and an angle of > 105° indicates a bicornuate uterus [10]. In our case, HSG was misinterpreted by radiologist and the mullerian anomaly was reported as bicornuate uterus because of the angle between the horns was > 105°.

The role of hysteroscopic septoplasty in patients with primary infertility remains controversial. Some investigators recommend treatment in this situation [12, 13] but others do not [14]. There is currently a lack of good randomized, controlled data. It should be emphasized, however, that a randomized, controlled trial is difficult to mount because this malformation is a cause of abortion and to a great extent it would not be ethical to randomize affected women to a “no treatment” group. Other investigators argue that the treatment is worth considering not only because of its possible beneficial effects on fecundity but also because of the potential benefits of reduced rates of miscarriage and preterm labor if these women conceive, especially those undergoing assisted reproductive techniques [13, 15].

In a recent series of septoplasty, in 2/64 (3%) patients uterine perforation occurred. In both cases no adjacent organs were injured and the complication was managed by bipolar coagulation. No sutures were applied. No postoperative episode of fever was noted [2]. According to our experience attempting to stop bleeding from the perforation with monopolar or bipolar energy modalities is not always succesfull. Furthermore, we believe that uterine wall integrity would be more securely maintained by the aid of suturing rather than coagulation, because thermal damage around the perforation could result more fibrotic healing. Therefore, we chose intracorporeal suture to repair the defect on the uterine wall.

Since HGS was interpreted as bicornuate uterus by radiologist, in our case we used combined laparoscopic approach and hysteroscopy for the diagnosis of septate uterus. Homer et al. reported that reliable diagnosis of the septate uterus depends on accurate assessment of the uterine fundal contour. They suggested that combined use of laparoscopy and hysteroscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis, although reports of two-dimensional, transvaginal, contrast ultrasound and three-dimensional ultrasound appear promising [16]. Carrascosa et al. recently demontrated that virtual hysterosalpingography clearly distinguishes bicornuate from septate uterus [17]. Although noninvazive new technologies ameliorate in the differential for bicornuate vs. septate uterus, laparoscopy still stays as the gold standart.

Lessons learned

1. Diagnosis of mullerian anomalies is not always possible with noninvasive methods. The reports of HSG should be confirmed by laparoscopic evaluation as the gold standart before attempting hysteroscopic intervention.

2. After laparoscopic confirmation of mullerian anomaly, trocars should be left in place till the end of the hysteroscopic resection of uterine septa.

3. During the laparoscopic chromopertubation the intrauterine pressure of the methylene blue may perforate the uterus, therefore tubal passage control might be postponed. The reason for perforation could be either due to overtreatment of the uterin septus or congenital weakening of the myometrium at the septal area.

4. Perforation with the pressure of methylene blue may require hemorrhage control and at this point intracorporeal suturing rather than coagulation of the bleeding site may cause less damage to the uterin wall ingegrity.

Funding Support

There is no financial support.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rackow BW, Arici A. Reproductive performance of women with mullerian anomalies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(3):229-237.

pubmed doi - Nouri K, Ott J, Huber JC, Fischer EM, Stogbauer L, Tempfer CB. Reproductive outcome after hysteroscopic septoplasty in patients with septate uterus—a retrospective cohort study and systematic review of the literature. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:52.

pubmed - Aydeniz B, Gruber IV, Schauf B, Kurek R, Meyer A, Wallwiener D. A multicenter survey of complications associated with 21,676 operative hysteroscopies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;104(2):160-164.

pubmed doi - Jansen FW, Vredevoogd CB, van Ulzen K, Hermans J, Trimbos JB, Trimbos-Kemper TC. Complications of hysteroscopy: a prospective, multicenter study. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(2):266-270.

pubmed doi - Shveiky D, Rojansky N, Revel A, Benshushan A, Laufer N, Shushan A. Complications of hysteroscopic surgery: "Beyond the learning curve". J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(2):218-222.

pubmed doi - Agostini A, Cravello L, Bretelle F, Shojai R, Roger V, Blanc B. Risk of uterine perforation during hysteroscopic surgery. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(3):264-267.

pubmed doi - Rock JA, Thompson JD. Te Linde's operative gynecology, (8th ed.), Lippincott-Raven, Phildelphia (1997).

- Faivre E, Fernandez H, Deffieux X, Gervaise A, Frydman R, Levaillant JM. Accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasonography in differential diagnosis of septate and bicornuate uterus compared with office hysteroscopy and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(1):101-106.

pubmed doi - Kupesic S. Clinical implications of sonographic detection of uterine anomalies for reproductive outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18(4):387-400.

pubmed doi - Troiano RN, McCarthy SM. Mullerian duct anomalies: imaging and clinical issues. Radiology. 2004;233(1):19-34.

pubmed doi - Braun P, Grau FV, Pons RM, Enguix DP. Is hysterosalpingography able to diagnose all uterine malformations correctly? A retrospective study. Eur J Radiol. 2005;53(2):274-279.

pubmed - Tomazevic T, Ban-Frangez H, Ribic-Pucelj M, Premru-Srsen T, Verdenik I. Small uterine septum is an important risk variable for preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;135(2):154-157.

pubmed doi - Doridot V, Gervaise A, Taylor S, Frydman R, Fernandez H. Obstetric outcome after endoscopic transection of the uterine septum. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(2):271-275.

pubmed doi - Ozgur K, Isikoglu M, Donmez L, Oehninger S. Is hysteroscopic correction of an incomplete uterine septum justified prior to IVF? Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14(3):335-340.

pubmed doi - Ban-Frangez H, Tomazevic T, Virant-Klun I, Verdenik I, Ribic-Pucelj M, Bokal EV. The outcome of singleton pregnancies after IVF/ICSI in women before and after hysteroscopic resection of a uterine septum compared to normal controls. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):184-187.

pubmed doi - Homer HA, Li TC, Cooke ID. The septate uterus: a review of management and reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(1):1-14.

pubmed doi - Carrascosa P, Sueldo C, Capunay C, Baronio M, Papier S. Virtual hysterosalpingography in the diagnosis of bicornuate versus septate uterus. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(5):1190-1192.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.