| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jcgo.org |

Case Report

Volume 10, Number 3, September 2021, pages 81-85

A Rare Case of Transformation of Endometrial Carcinoma Into Uterine Carcinosarcoma

Leela Sharath Pillarisettya, d, Srikanth Mukkerab, Maneesh Mannemb, Jinal Patelc, Subash Nagallaa, Anusha Ammub, Lakshmi Alaharib

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin, Odessa, TX, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin, Odessa, TX, USA

cDepartment of Family Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin, Odessa, TX, USA

dCorresponding Author: Leela Sharath Pillarisetty, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at the Permian Basin, 405 N Tom Green Avenue, Odessa, TX 79761, USA

Manuscript submitted August 25, 2020, accepted March 16, 2021, published online September 28, 2021

Short title: Transformation of Endometrial Carcinoma

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo677

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Uterine carcinosarcoma (previously called malignant mixed Mullerian tumor) is a rare and aggressive cancer that is considered a high-risk variant of endometrial adenocarcinoma because of the resemblance in risk factors and clinical presentation with endometrial carcinoma. In the United States, the incidence of carcinosarcoma is approximately 1 to 4 per 100,000 women. The clinical features, diagnosis, staging, and treatment of uterine carcinosarcoma will be discussed in this topic review. To our knowledge, this is one of the few reported cases of endometrial carcinoma that has transformed into uterine carcinosarcoma.

Keywords: Uterine carcinosarcoma; Malignant mixed Mullerian tumor; Chemotherapy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) is a rare and invasive de-differentiated neoplasm that constitutes both an epithelial and a stromal component (sarcoma). This article reviews the literature applicable to the risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of women with UCS. PubMed was used for the literature search on UCS. Immunostaining for paired box gene 8 (PAX8), hepatic nuclear factor 1 (HNF-1), estrogen receptor (ER), tumor protein (p53), programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1), and growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor (GHRH-R) was positive in the majority of cases. The patients usually present with abdominal pain, post-menopausal vaginal bleeding, and a rapidly enlarging uterus. Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, and endometrial biopsy are needed to confirm the disease and any metastases. Most of the management for UCS is similar to the invasive endometrial carcinoma and treated with surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Due to late presentation, rapid spread, high recurrence rate, and poor prognosis of the UCS, there is a need for clinical trials on the early detection of the condition as well as targeted therapy on immunohistochemical markers.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

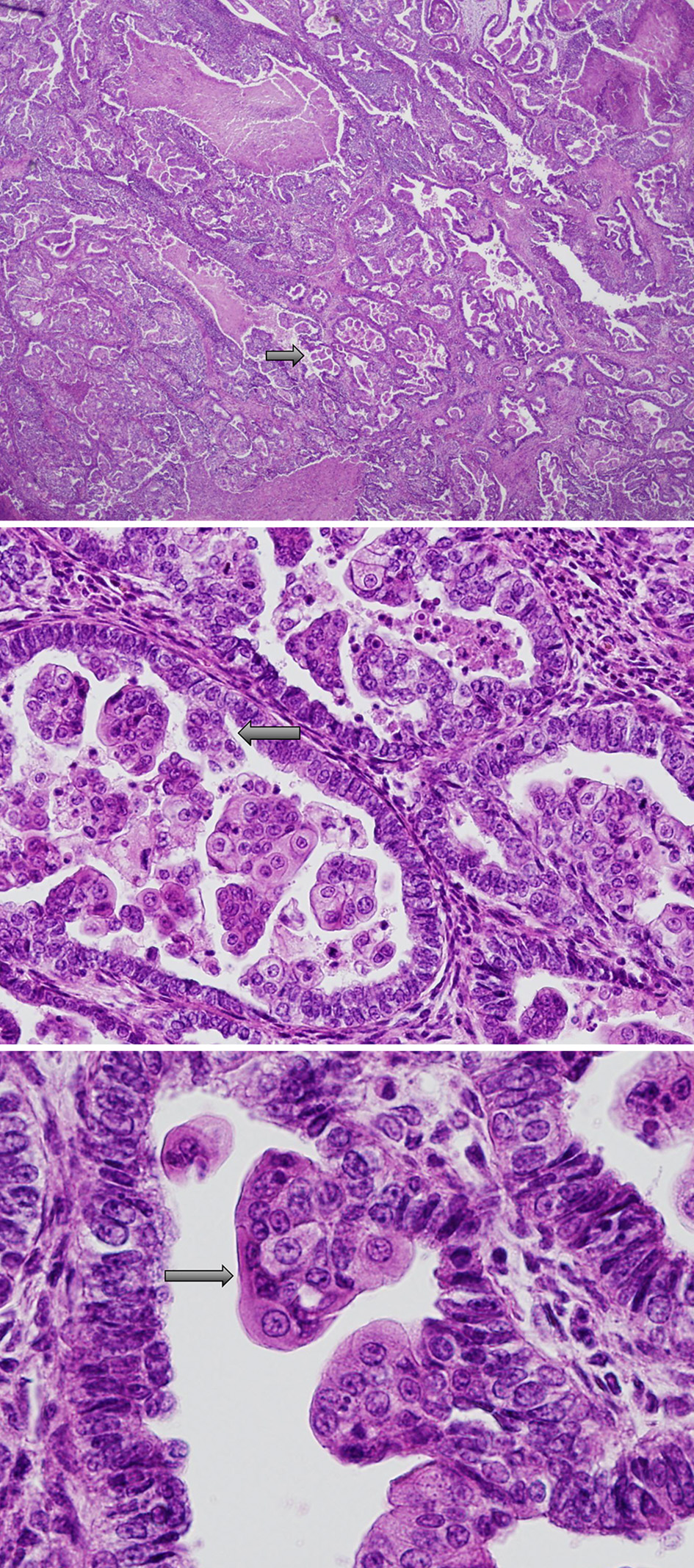

A 76-year-old woman with a history of type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and deep vein thrombosis presented to the office with the chief complaint of intermittent vaginal bleeding for 4 weeks. On physical examination, her vital signs were stable. Her abdomen was soft, non-tender, mildly distended with normoactive bowel sounds. The gynecological examination was normal without any evidence of active bleeding. The laboratory findings revealed hemoglobin of 9.5 g/dL. Ultrasound of the pelvis showed a uterus size of 4.6 × 3.7 × 4.1 cm with an endometrial thickness of 2.5 cm, and both ovaries were within normal limits. An endometrial biopsy was done, and it revealed benign endometrial polyp. Subsequently, she underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy due to recurrent bleeding episodes. The final pathology specimen showed that she had endometrial adenocarcinoma in situ (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging stage 1A) with secretory cell changes (Fig. 1) developing within an endometrial polyp. There was no myometrial invasion. The patient was then referred to a medical oncologist who recommended no additional treatment based on the standard recommendations for the FIGO stage 1A.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma in situ (FIGO staging: stage 1A) with secretory cell changes. Black arrows demonstrate secretory cell changes. FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. |

We recommended observation alone and asked the patient to follow up every 2 months or earlier for any new or worsening symptoms. Unfortunately, the patient was not compliant with her follow-up visits.

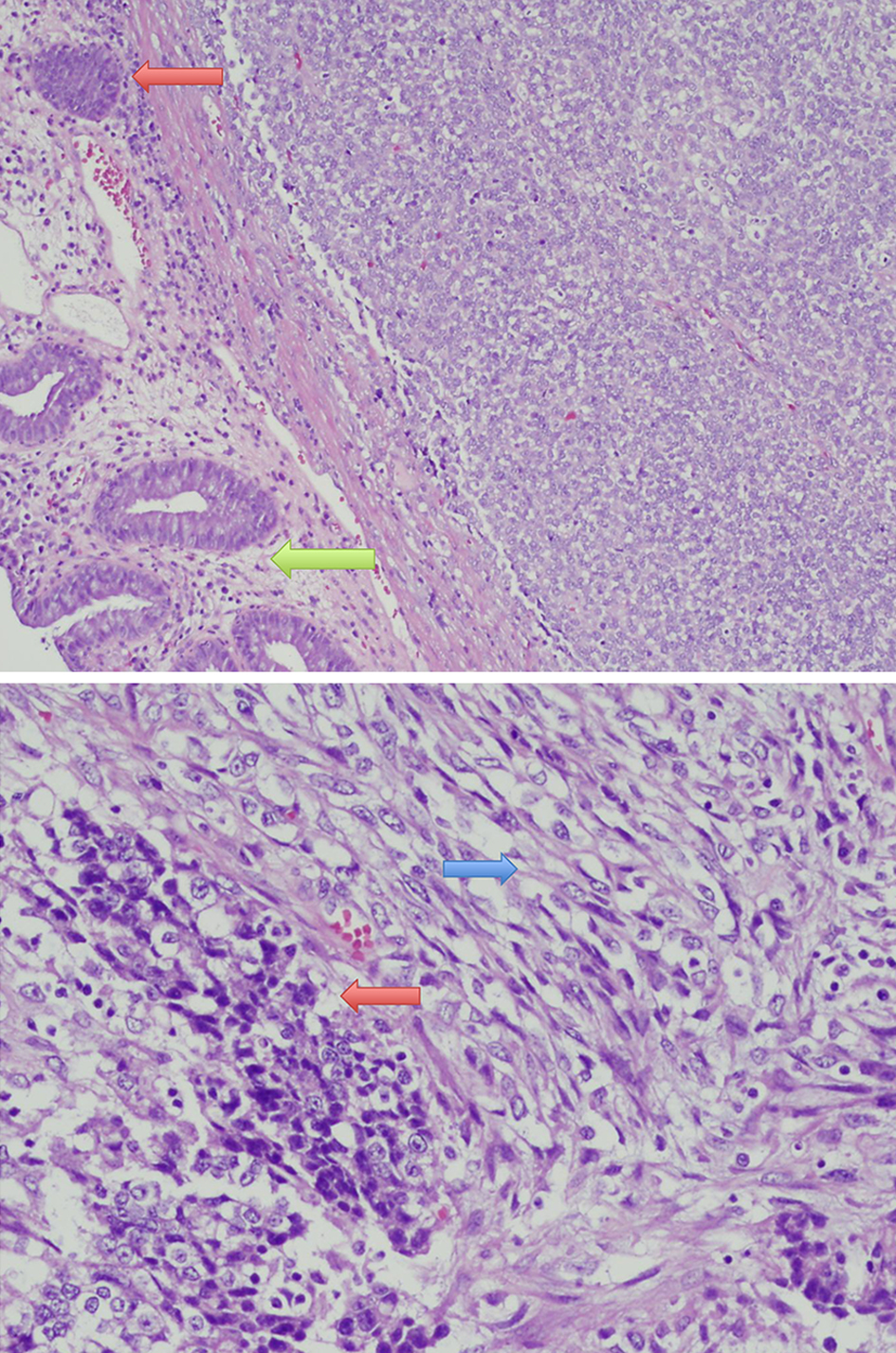

Five months later, she came to the office with left lower quadrant abdominal pain, constipation, and hemorrhoids for 1 week. On physical examination, she was found to have a rigid palpable mass in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a large pelvic mass measuring about 6.4 × 5.4 × 4.1 cm, possibly attached to the sigmoid colon extending from the vaginal cuff. A general surgeon was consulted, and a laparotomy was performed. During the procedure, she was found to have a large, firm mass originating from the sigmoid colon, confirming the CT findings. Resection of the mass and part of the sigmoid colon was performed, and an end-to-end anastomosis was done followed by pelvic washing. As per the frozen biopsy section, the tumor was of stromal origin and the final pathology report revealed a high-grade biphasic malignant neoplasm consistent with metastasis from uterine primary extending through the wall of the colon with mucosal ulceration confirming malignant mixed Mullerian tumor (uterine carcinosarcoma) (Fig. 2). The postoperative period was uneventful, and she was discharged home after 1 week. She was recommended to undergo chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy which the patient declined again. The patient opted for hospice care and died 2 months later.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Uterine carcinosarcoma metastasized to the colon. Orange arrows demonstrate carcinoma cells. Green arrow demonstrates normal colonic mucosa. Blue arrow demonstrates sarcomatous cells. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

UCS is a rare and invasive metaplastic cancer that constitutes both an epithelial component (carcinoma) and a stromal component (sarcoma) arising from a single malignant epithelial clone [1]. UCS represents less than 5% of all uterine tumors but accounts for 15% of all deaths caused by uterine malignancy [2]. Common sites of extrauterine spread include lymph nodes, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and omentum [3]. African American and older women (> 60 years) have a higher incidence of UCS [4]. Risk factors include obesity, nulliparity, history of pelvic radiation, and use of exogenous estrogen and tamoxifen. Progestin-containing contraceptives are protective [5, 6].

UCSs are “biphasic”, mixed epithelial and stromal tumors, with both components being malignant [7]. Homologous carcinosarcomas have a sarcomatous component of fibrosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma, and/or leiomyosarcoma. By contrast, the heterologous type includes sarcomatous components that are made up of tissues non-native to the uterus [8]. Immunostaining for PAX8, HNF-1, ER, p53, PD-L1, and GHRH-R was positive in the majority of cases of UCS. Clinically high stage UCS is associated with the expression of p53. Immunostaining for PD-L1 was positive in 70% of cases and the GHRH-R was positive in 88% of cases and mostly expressed in the epithelial component [9]. UCS has also been reported in connection with a familial germline MutL homolog (MLH1) gene mutation resulting in loss of MLH1 protein expression [10].

Clinical features and diagnosis

The patients usually present with abdominal pain, post-menopausal vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and a rapidly enlarging uterus [11]. On physical exam, a pelvic mass may be palpated or seen protruding through the cervical os. UCS may present with an extrauterine disease in 60% of cases, and recurrence will occur in more than 50% despite surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy [12].

On ultrasound, carcinosarcomas are hyperechoic compared with the myometrium. They often form a large polyp that fills the endometrial cavity. On the CT scan, they appear as heterogeneous, hypodense masses with dilatation of the endometrial canal [13]. In the laboratory studies, anemia is seen in a few patients due to vaginal bleeding. The tumor marker Cancer Antigen 125 (CA-125) can be elevated in carcinosarcoma and it appears to correlate with metastases or tumor bulk [14]. Most patients are diagnosed by endometrial biopsy. A smaller number of patients are diagnosed after hysterectomy for the treatment of presumed fibroids or pelvic pain.

If a woman presents with clinical features suggestive of uterine malignancy, endometrial sampling is usually performed. However, if the endometrial biopsy is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, further workup like pelvic sonography with or without directed biopsy is required. In a study involving women with carcinosarcoma of the uterus, endometrial sampling was diagnostic in only 59% of women [15].

Carcinosarcoma is diagnosed based on the histologic evidence of both carcinomatous and sarcomatous cells with the invasion of the stroma. The patient should undergo additional imaging like CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to rule out metastatic disease because more than half of the patients will have metastases at the time of the initial presentation.

Staging

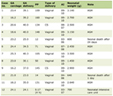

FIGO staging of endometrial carcinoma and UCS [16] is shown in Table 1.

Click to view | Table 1. FIGO Staging of Endometrial Carcinoma and Uterine Carcinosarcoma |

Management

UCS metastasizes through lymphatic vessels and present with recurrences in the pelvis like high-grade endometrial carcinomas. The current standard treatment is similar to that of high-grade endometrial carcinomas: at least a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with possible tumor debulking, platinum-based chemotherapy depending on the stage, and possible adjuvant radiotherapy for local control.

Surgery is recommended for patients with no evidence of metastatic disease [17]. Surgical cytoreduction is reserved for patients with extrauterine disease limited to the peritoneum [18]. For patients with extra-abdominal metastatic disease, treatment goals are palliative.

Complete surgical staging includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection, omentectomy, cytology of peritoneal washings, and biopsies of peritoneal surfaces.

For stage IA, chemotherapy has a greater impact on systemic control of disease than observation alone [19]. For patients with surgically staged IB to IV carcinosarcoma, chemotherapy is preferred to radiotherapy or observation [20, 21]. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel is the preferred adjuvant therapy for metastatic disease [22].

Prognosis

5-year disease-free survival rates depend on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage of the disease. They were 59%, 22%, and 9% for women with stage I/II, III, or IV disease, respectively [23].

Conclusion

Uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) is a rare and aggressive cancer due to the metaplastic transformation of carcinomatous elements into sarcoma. Though it is managed by surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the recurrence rate is high and the overall prognosis is poor. Rapid progression of the disease in our patient might be due to non-compliance with the recommendations and failure to follow-up. Focused clinical trials on the early detection, recurrence prevention strategies and tumor marker directed therapy are required.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was taken from the patient after clearly explaining the benefits and risks of the usage of the patient’s data in this case report.

Author Contributions

LSP, SM, and MM: case report, discussion, and images. JP, SN, AA, and LA: literature search, introduction, abstract, and references.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Somarelli JA, Boss MK, Epstein JI, Armstrong AJ, Garcia-Blanco MA. Carcinosarcomas: tumors in transition? Histol Histopathol. 2015;30(6):673-687.

- Cantrell LA, Blank SV, Duska LR. Uterine carcinosarcoma: A review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):581-588.

doi pubmed - Bitterman P, Chun B, Kurman RJ. The significance of epithelial differentiation in mixed mesodermal tumors of the uterus. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14(4):317-328.

doi pubmed - Sherman ME, Devesa SS. Analysis of racial differences in incidence, survival, and mortality for malignant tumors of the uterine corpus. Cancer. 2003;98(1):176-186.

doi pubmed - Zelmanowicz A, Hildesheim A, Sherman ME, Sturgeon SR, Kurman RJ, Barrett RJ, Berman ML, et al. Evidence for a common etiology for endometrial carcinomas and malignant mixed mullerian tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69(3):253-257.

doi pubmed - Fotiou S, Hatjieleftheriou G, Kyrousis G, Kokka F, Apostolikas N. Long-term tamoxifen treatment: a possible aetiological factor in the development of uterine carcinosarcoma: two case-reports and review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(3B):2015-2020.

- Gonzalez Bosquet J, Terstriep SA, Cliby WA, Brown-Jones M, Kaur JS, Podratz KC, Keeney GL. The impact of multi-modal therapy on survival for uterine carcinosarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(3):419-423.

doi pubmed - Jin Z, Ogata S, Tamura G, Katayama Y, Fukase M, Yajima M, Motoyama T. Carcinosarcomas (malignant mullerian mixed tumors) of the uterus and ovary: a genetic study with special reference to histogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003;22(4):368-373.

doi pubmed - Jones TE, Pradhan D, Dabbs DJ, Bhargava R, Onisko A, Jones MW. Immunohistochemical markers with potential diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic significance in uterine carcinosarcoma: a clinicopathologic study of 43 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2021;40(1):84-93.

doi pubmed - South SA, Hutton M, Farrell C, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Rodabaugh KJ. Uterine carcinosarcoma associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 2):543-545.

doi pubmed - Dave KS, Chauhan A, Bhansali R, Arora R, Purohit S. Uterine carcinosarcomas: 8-year single center experience of 25 cases. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2011;32(3):149-153.

doi pubmed - Felix AS, Stone RA, Bowser R, Chivukula M, Edwards RP, Weissfeld JL, Linkov F. Comparison of survival outcomes between patients with malignant mixed mullerian tumors and high-grade endometrioid, clear cell, and papillary serous endometrial cancers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(5):877-884.

doi pubmed - Teo SY, Babagbemi KT, Peters HE, Mortele KJ. Primary malignant mixed mullerian tumor of the uterus: findings on sonography, CT, and gadolinium-enhanced MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(1):278-283.

doi pubmed - Huang GS, Chiu LG, Gebb JS, Gunter MJ, Sukumvanich P, Goldberg GL, Einstein MH. Serum CA125 predicts extrauterine disease and survival in uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(3):513-517.

doi pubmed - Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Burke W, Cohen CJ, Wright JD. The utility of preoperative endometrial sampling for the detection of uterine sarcomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110(1):43-48.

doi pubmed - Corpus uteri: Carcinoma and carcinosarcoma TNM staging AJCC UICC, 8th edition.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Endometrial carcinoma. Version 3. 2012.

- Tanner EJ, Leitao MM, Jr., Garg K, Chi DS, Sonoda Y, Gardner GJ, Barakat RR, et al. The role of cytoreductive surgery for newly diagnosed advanced-stage uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123(3):548-552.

doi pubmed - Powell MA, Filiaci VL, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of paclitaxel (P) plus carboplatin (C) versus paclitaxel plus ifosfamide (I) in chemotherapy-naive patients with stage I-IV, persistent or recurrent carcinosarcoma of the uterus or ovary: an NRG oncology trial.

- Matei D, Filiaci V, Randall ME, Mutch D, Steinhoff MM, DiSilvestro PA, Moxley KM, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy plus radiation for locally advanced endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2317-2326.

doi pubmed - Wolfson AH, Brady MF, Rocereto T, Mannel RS, Lee YC, Futoran RJ, Cohn DE, et al. A gynecologic oncology group randomized phase III trial of whole abdominal irradiation (WAI) vs. cisplatin-ifosfamide and mesna (CIM) as post-surgical therapy in stage I-IV carcinosarcoma (CS) of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107(2):177-185.

doi pubmed - Powell MA, Filiaci VL, Rose PG, Mannel RS, Hanjani P, Degeest K, Miller BE, et al. Phase II evaluation of paclitaxel and carboplatin in the treatment of carcinosarcoma of the uterus: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2727-2731.

doi pubmed - Villena-Heinsen C, Diesing D, Fischer D, Griesinger G, Maas N, Diedrich K, Friedrich M. Carcinosarcomas—a retrospective analysis of 21 patients. Anticancer Res. 2006;26(6C):4817-4823.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.