| Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics, ISSN 1927-1271 print, 1927-128X online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Gynecol Obstet and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.jcgo.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 2, June 2024, pages 35-40

Treatment of Primary Pneumothorax in Pregnancy With Thoracostomy Tube and Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery

Shelly Thaia, e, Sylwia Polaka, Vanessa Gibsonb, Shahriyour Andazc, Dina El Kadyd

aDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, NY 11572, USA

bDepartment of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, NY 11572, USA

cDepartment of Thoracic Oncology, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, NY 11572, USA

dDepartment of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, NY 11572, USA

eCorresponding Author: Shelly Thai, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mount Sinai South Nassau, Oceanside, NY 11572, USA

Manuscript submitted December 13, 2023, accepted March 5, 2024, published online April 13, 2024

Short title: Spontaneous Pneumothorax in Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcgo938

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Spontaneous primary pneumothorax is a rare, potentially life-threatening complication that can occur during a pregnancy. Due to the rarity of this condition (1.2 - 6 in 100,000 women), with even less prevalence in pregnancy, guidelines regarding optimal treatment are lacking and are limited to case reports and case series. Management is primarily based on a risk benefit ratio for the mother and unborn child. We present a case of a pregnant patient presenting with chest pain and shortness of breath diagnosed with a spontaneous pneumothorax during the second trimester of pregnancy. Initial treatment with thoracostomy tube was not successful. The patient underwent a successful video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) pleurodesis with a wedge blebectomy. She continued the pregnancy with no recurrences. After failed thoracostomy tube, surgical intervention in pregnancy can be offered as definitive management for pregnant women.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Pneumothorax; Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Dyspnea in pregnancy can have a multitude of different etiologies ranging from physiological shortness of breath to life-threatening medical conditions, and the differentiation between them can be difficult. Spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy is a rare event with less than 100 cases reported, however it should always be included in the differential diagnosis of dyspnea. Early recognition and treatment are important to prevent further complications in pregnancy. We present a case of a patient in her second trimester of pregnancy with a spontaneous pneumothorax, which necessitated surgical intervention with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) which was successful.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 41-year-old woman, gravida 1 para 0 (G1P0), at 21 weeks, presented to the Emergency Department with sudden onset severe left sided chest pain and shortness of breath after blowing her nose. There was no history of trauma. She was a non-smoker, with no significant medical history. Her obstetrical history was only significant for advanced maternal age.

Diagnosis

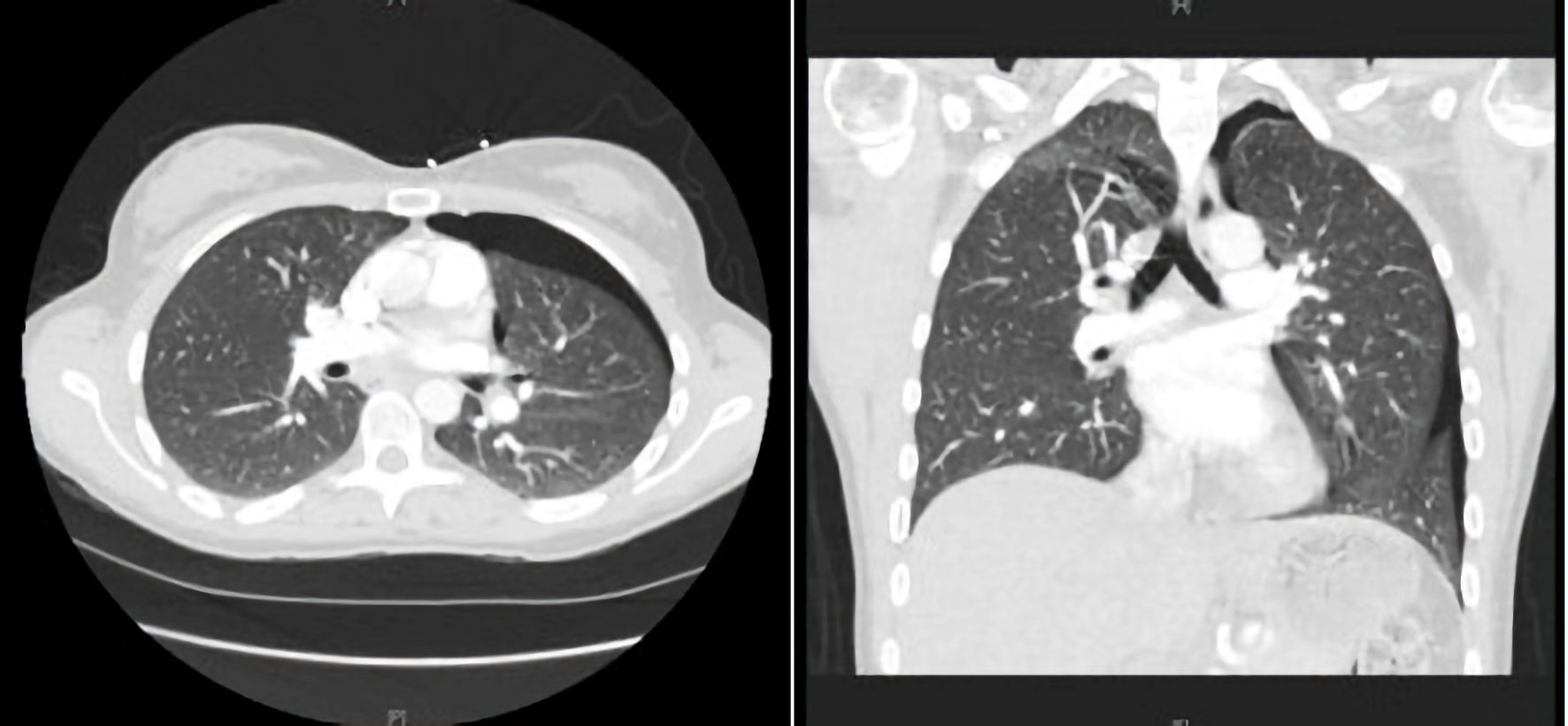

Vital signs showed blood pressure 127/77 mm Hg, heart rate 68 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate 20, saturating 97-100% on room air. Physical examination revealed a tall female with a body mass index (BMI) of 21. Auscultation of her lungs revealed diminished breath sounds over her left upper lung fields. Fetal heart rate was 140 bpm and obstetrical ultrasound was normal. Due to initial suspicion of a pulmonary embolism, the patient underwent a computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Imaging revealed a small left sided apical pneumothorax and no evidence of pulmonary embolism (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. CTPA revealing left sided pneumothorax. CTPA: computed tomography pulmonary angiography. |

Treatment

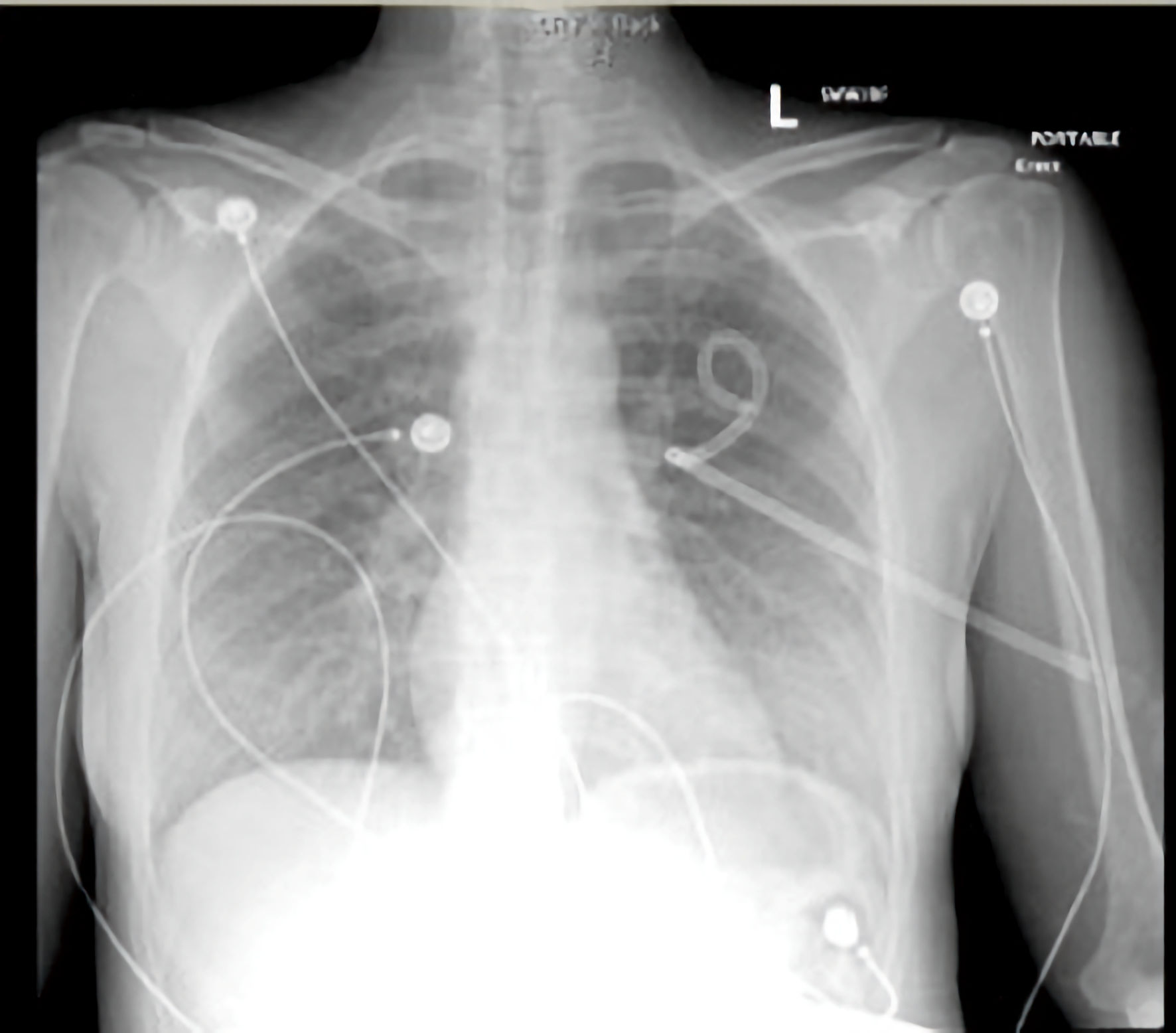

On admission, a small-bore chest tube was placed and connected to low continuous suction (Fig. 2). She was admitted to the cardiothoracic service for management of the pneumothorax. A repeat chest X-ray post thoracostomy tube insertion had shown a small residual apical pneumothorax. Trials of clamping of the thoracostomy tube were unsuccessful over a course of 5 days. A multidisciplinary team of specialists comprising of general obstetrics, maternal-fetal medicine, and cardiothoracic surgery was assembled to discuss the patient’s plan of care. The patient was offered expectant management, chemical pleurodesis, and surgical management with a VATS procedure. Due to the failure of the initial intervention and increased fetal risks associated with a chemical pleurodesis, the patient had opted to undergo the surgical intervention with the VATS procedure. On the sixth hospital day the patient underwent a VATS procedure under general anesthesia with bronchoscopy-assisted intubation with an apical wedge blebectomy. At the end of the procedure the lung was inflated under positive pressure ventilation. The chest tube was connected to a Pleur-evac reservoir. In the recovery period, the surgery team was able to successfully remove the remaining chest tube without any recurrences of the pneumothorax. The patient was then discharged from the hospital 2 weeks after the procedure.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Chest X-ray after thoracostomy tube placement with residual apical pneumothorax. |

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient remained asymptomatic for the remainder of her pregnancy. She decided, despite adequate counseling, that she did not want to undergo spontaneous labor, and elected for a primary cesarean section at 39.0 weeks of gestation. The cesarean section was performed under spinal anesthesia with blood loss of 600 mL, due to lower uterine segment atony, resolved with one dose of methergine. The postoperative course was unremarkable, and patient was discharged home in stable condition on postoperative day 3, with no further complaints or hospitalizations for symptoms secondary to pneumothorax. Chest radiography was repeated at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year follow-up with no recurrence of pneumothorax.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

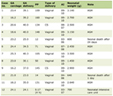

A spontaneous pneumothorax is the presence of gas in the pleural space, in the absence of an external event, in a healthy person without any underlying lung disease. This condition is extremely rare in pregnancy [1]. Due to the low prevalence of this condition in pregnancy, the guidelines for management are not well established and largely based on case reports. Therefore, we present this case report alongside a narrative review of the literature to determine treatment modalities and review outcomes. A literature review was performed including all cases of pneumothorax in pregnant women from PubMed and Google Scholar using search terms “pneumothorax”, “pregnancy”, “VATS”, from 1990 to current (Table 1) [2-27]. We excluded cases of pneumothorax which were outside of pregnancy.

Click to view | Table 1. Case Reports of Spontaneous Pneumothorax in Pregnancy |

There are several modalities that can assist in the diagnosis of pneumothorax in pregnancy, and such modalities should not be delayed in pregnancy for fear of radiation exposure. Chest radiographs are needed to confirm a diagnosis of spontaneous pneumothorax. When the maternal abdomen is shielded, the estimated radiation dose to the uterus is 1 - 2 mrad per examination. One mrad is equal to 0.01 mGy. Thus, a chest radiograph can be done without placing the fetus at substantial risk from ionization radiation. The use of ultrasound has been studied; however, the main value of this technique was mostly appreciated in the management of trauma patients. Computed tomography (CT) is another useful imaging technique when considering surgical treatment. In the presented case, the imaging modality that was chosen was a CTPA due to initial suspicion of a pulmonary embolism, similar to the case reported by La Verde et al [9]. The fetal radiation dose associated with this imaging modality is 0.01 - 0.66 mGy, which is small, and likely not associated with any fetal abnormalities at this gestational age and dosage. Ultimately, diagnostic images should not be delayed in the evaluation of suspected pneumothorax.

The importance of prompt diagnosis and management of a spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy is of grave importance, since hypoxemia is not well tolerated in the fetus [3, 4]. In general, the same treatment criteria used for pneumothorax in non-pregnant patients apply to the pregnant population [5]. When considering a management strategy for the patient, the size of the pneumothorax is not as important as the degree of clinical compromise. Patients with a medical history of previous lung disease may not be able to tolerate the pneumothorax as well as a patient with no comorbidities. Admission and close observation of the patient is usually done for those with small pneumothoraxes. In this case, intervention was indicated since the patient was persistently symptomatic and unable to maintain supine position without feeling short of breath. In these patients, needle aspiration or chest tube placement should be considered as first-line management [28]. Although there were reservations in placing chest tubes in pregnancy, these case studies have shown that longer-term use of intercostal drainage as a temporizing measure for spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy is safe and effective. Our patient continued to have persistent pneumothorax despite chest tube placement. She was given the options of continuing with expectant management versus chemical pleurodesis, versus surgical intervention. Chemical pleurodesis involves instillation of a substance into the pleural space which would lead to an inflammatory response with adhesion formation. There are many sclerosing agents available for use such as tetracycline, minocycline, doxycycline, and talc. The recurrence rate for tetracycline was noted to be as high as 20% [28]. The use of tetracycline would also not be recommended in pregnancy due to the possible teratogenic effects on the fetus. Due to limited data regarding the safety profile of chemical pleurodesis in pregnancy, the patient elected to undergo VATS with an apical blebectomy [6]. VATS with pleurectomy is noted to have a lower recurrence rate compared to chemical pleurodesis alone, of about 5%.

On review of the literature, it was noted that chest tube placement alone, although effective, did result in many recurrences of pneumothorax in pregnant women, which required multiple chest tube placements throughout the course of their pregnancy. About 34% of the reviewed cases had resolution of their symptoms after the primary thoracostomy tube placement, and around 55% of the remaining patients were required to undergo a surgical intervention with VATS or open thoracotomy procedure. All of the cases of surgical intervention reported in literature were successful. In a case study, Lateef et al showed that recurrence of pneumothorax occurred in 2 weeks after treatment with chest tube insertion [7]. In another case series, Kavurmaci et al showed a case where VATS was completed in pregnancy after recurrence of pneumothorax and discharged without adverse outcomes or recurrence [8]. Repeat evaluation was done postpartum with no findings of recurrence or complications. In a case series, Agrafiotis et al [1] concluded that VATS procedure should be standard of care. In our case, the VATS procedure was successful, and the patient did not have any recurrences for the remainder of her pregnancy. It was a successful second-line therapy for a pregnant patient who was not responding to the chest tube alone. This appears to be a reasonable strategy for the treatment of pneumothorax in a pregnant patient. If surgical approach is chosen, adequate oxygenation during the procedure and monitoring of the fetus based on gestational age should also be taken into consideration with these cases.

Once pregnant women have recovered from the pneumothorax, vaginal delivery is not an absolute contraindication [7]. Patients should be counseled that there is an increased chance of recurrence during labor of around 30-40%. The study of La Verde et al showed that pneumomediastinum is more likely to occur in the second stage of labor [9]. For patients who have not received definitive surgical therapy, epidural anesthesia and operative vaginal delivery may be recommended to prevent increased intrathoracic pressure due to the expulsive efforts during the second stage of labor and possible worsening or recurrence of pneumothorax.

In summary, spontaneous pneumothorax is a rare and serious complication that can affect pregnancy. Physiological changes of pregnancy in the mother can make it difficult for prompt diagnosis. To avoid complications, early diagnosis through imaging studies should be obtained, with appropriate counseling of the pregnant patient regarding the radiation exposure. Treatment guidelines should be the same as for non-obstetrical patients, however chemical pleurodesis has limited data and safety profiles available.

One of the strengths of this case study was our ability to record a continuity of care from early pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Our literature review included a patient population with a wide range of gestational ages, demonstrating that the VATS procedure has been successfully performed at most gestational ages. This report has the usual limitations of a case study and series and may not be generalizable to all patients, especially in patients with additional comorbidities (cardiopulmonary diseases).

When conservative management of pneumothorax is not successful, the evidence from culmination of case series and our case demonstrates that VATS procedure is an effective surgical treatment in pregnancy for definitive management of pneumothorax. In cases where there is a high risk of pneumothorax recurrence, VATS procedure can be considered as first-line therapy. Further studies are indicated to determine the ideal mode of treatment for pregnancy.

Learning points

Avoidance of delay and performing appropriate diagnostics studies in pregnant women is imperative in the diagnosis of pneumothorax in pregnancy. Treatment can be conservative with chest tube, or treatment can be offered with surgical intervention. Surgical intervention has appeared to be successful when performed with low overall recurrence risks. Recurrences have been reported during the labor and delivery process, and caution is advised. More studies are needed to determine the ideal treatment algorithm in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained.

Author Contributions

Shelly Thai, MD, conducted literacy search and wrote manuscript. Sylwia Polak, MD, conducted literacy search, and contributed to manuscript. Vanessa Gibson, MD, contributed to study design. Shahriyour Andaz, MD, contributed to study design. Dina El Kady, MD, FACOG, contributed to study design, and edits of manuscript

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article

Abbreviations

VATS: video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery; BMI: body mass index; CT: computed tomography; CTPA: computed tomography pulmonary angiography; bpm: beats per minute

| References | ▴Top |

- Agrafiotis A, Assouad J, Lardinois I, Markou G. Pneumothorax and pregnancy: a systemic review of the current literature and proposal of treatment recommendations. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;69:95-100.

doi - Annaiah TK, Reynolds SF. Spontaneous pneumothorax-a rare complication of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(1):80-82.

doi pubmed - Nwaejike N, Aldam P, Pulimood T, Giles R, Brockelsby J, Fuld J, Hughes J, et al. A case of recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy treated with video assisted thoracoscopic surgery. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr0520114282.

doi pubmed pmc - Sathiyathasan S, Jeyanthan K, Furtado G, Hamid R. Pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum in pregnancy: a case report. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2009;2009:465180.

doi pubmed pmc - Jain P, Goswami K. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:81.

doi pubmed pmc - Yasuda I, Hidaka T, Kusabiraki T, Kochi K, Yasoshima K, Takagawa K, Saito S. Chemical pleurodesis with autologous blood and freeze-dried concentrated human thrombin improved spontaneous pneumothorax and thoracic endometriosis: The first case involving a pregnant woman. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57(3):449-451.

doi pubmed - Lateef N, Dawood M, Sharma K, Tauseef A, Munir MA, Godbout E. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy - a case report and review of literature. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2018;8(3):115-118.

doi pubmed pmc - Kavurmaci O, Akcam TI, Kavurmaci SA, Turhan K, Cagirici U. Pneumothorax: a rare entity during pregnancy. Turk Thorac J. 2019;20(3):206-208.

doi pubmed pmc - La Verde M, Palmisano A, Iavarone I, Ronsini C, Labriola D, Cianci S, Schettino F, et al. A rare complication during vaginal delivery, Hamman's syndrome: a case report and systematic review of case reports. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4618.

doi pubmed pmc - Vinay Kumar A, Raghukanth A. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2014;56(1):33-35.

pubmed - Lal A, Anderson G, Cowen M, Lindow S, Arnold AG. Pneumothorax and pregnancy. Chest. 2007;132(3):1044-1048.

doi pubmed - Garg R, Sanjay, Das V, Usman K, Rungta S, Prasad R. Spontaneous pneumothorax: an unusual complication of pregnancy—a case report and review of literature. Ann Thorac Med. 2008;3(3):104-105.

doi pubmed pmc - Avital A, Galante O, Baron J, Smoliakov A, Heimer D, Avnun LS. Spontaneous pneumothorax in the third trimester of pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr07.2009.2068.

doi pubmed pmc - Levine AJ, Collins FJ. Treatment of pneumothorax during pregnancy. Thorax. 1996;51(3):338-339:discussion 340-331.

doi pubmed pmc - Akcay O, Uysal A, Samancilar O, Ceylan KC, Sevinc S, Kaya SO. An unusual emergency condition in pregnancy: pneumothorax. Case series and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;287(2):391-394.

doi pubmed - Mohammadi A, Ghasemi Rad M, Afrasiabi K. Spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy: a case report. Tuberk Toraks. 2011;59(4):396-398.

doi pubmed - Tanase Y, Yamada T, Kawaryu Y, Yoshida M, Kawai S. A case of spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy and review of the literature. Kobe J Med Sci. 2007;53(5):251-255.

pubmed - Miyasita M, Koga A, Kiyonari N, Yosimura H. [Spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature]. Kyobu Geka. 1991;44(7):576-578.

pubmed - Onodera K, Noda M, Okada Y, Kondo T. Awake video-thoracoscopic surgery for intractable pneumothorax in pregnancy by using a single portal plus puncture. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17(2):438-440.

doi pubmed pmc - Pinedo-Onofre JA, Ortiz-Castillo FG, Guevara-Torres L, Aguillon-Luna A. [Spontaneous pneumothorax in pregnancy. Case report]. Cir Cir. 2006;74(6):469-471.

pubmed - Yotsumoto T, Sano A, Sato Y. [Spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy successfully managed with a thoracic vent before surgical therapy; report of a case]. Kyobu Geka. 2015;68(12):1031-1033.

pubmed - VanWinter JT, Nichols FC, 3rd, Pairolero PC, Ney JA, Ogburn PL, Jr. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(3):249-252.

doi pubmed - Reid CJ, Burgin GA. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical pleurodesis for persistent spontaneous pneumothorax in late pregnancy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28(2):208-210.

doi pubmed - Gorospe L, Puente S, Madrid C, Novo S, Gil-Alonso JL, Guntinas A. Spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy. South Med J. 2002;95(5):555-558.

pubmed - Wong MK, Leung WC, Wang JK, Lao TT, Ip MS, Lam WK, Ho JC. Recurrent pneumothorax in pregnancy: what should we do after placing an intercostal drain. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12(5):375-380.

pubmed - Sills ES, Meinecke HM, Dixson GR, Johnson AM. Management approach for recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax in consecutive pregnancies based on clinical and radiographic findings. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:35.

doi pubmed pmc - Hamid MFA, Aziz H, Ian SC, Lin ABY. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax during pregnancy managed conservatively: a case report. Med J Malaysia. 2016;71(2):93-95.

- MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J, BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii18-ii31.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Gynecology and Obstetrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.